Walking wins: The prize-winning projects helping people get back on their feet

For most of us, walking is so basic an action that it seems unremarkable, but these award-winning landscape architecture projects demonstrate that thoughtful pedestrian design can contribute far more than we realise to our enjoyment of the urban landscape.

‘Walking’ is a deceptively simple activity. From a stroll to the shops or days-long immersive hikes in the bush, the experience of traversing the ground with your body can vary vastly. Much has been said about the economic and health benefits of cycling during the pandemic, but the efficiency of such swift personal mobility and its rapid uptake is only one of our recent urban wins. The intimate pleasures of walking are quite different, heightening an appreciation for the detail of places we pass through.

Urban perambulations

Pedestrianised European city and town centres have served as models for desirable contemporary urbanism for many years. COVID-19 has seen streets suddenly, if also troublingly, void of cars. Without them, we have been able to appreciate urban centres as places to enjoy walking. Luckily, the transformation of some of Australia’s townscapes towards richer pedestrian experiences was already well afoot before the pandemic hit.

The Brunswick Town Hall Precinct Streetscape Upgrade by Moreland City Council is just such a work. The winner of a 2020 Australian Institute of Landscape Architects (AILA) Victoria Award of Excellence for Civic Landscape, the precinct comprises three linked streetscape projects around a busy intersection just north of Melbourne. The award jury recognised the complexity of a project that “consolidates a series of thoughtful and multi-layered civic spaces” and “incorporates pedestrian and cyclist circulation, spaces for gathering, performance and rest”.

This includes wider footpaths, new seating and planting, bluestone kerbs and a channel with rain gardens. The public streetscape, which in some places features paving incorporating literary quotes, knits together not only the Town Hall, but also Brunswick Library, Counihan Gallery, Brunswick Baths, Brunswick Mechanics Institute, RMIT and Brunswick Secondary School.

Dawson Street, Brunswick upgrade by Moreland City Council.

The upgrade to the streetscape at the Brunswick Mechanics Institute for Moreland City Council.

New public streetscape outside the Brunswick Mechanics Institute for Moreland City Council.

Saxon Lane, Brunswick streetscape upgrade by and for Moreland City Council.

A little to the west, neighbouring Moonee Valley City Council won a civic award for Union Road Streetscape Improvements. Located on a busy commercial strip, the project pays particular attention to elderly residents, with the jury noting that these spaces have been designed to help people with dementia navigate them. A walk to the shops is an important social activity with both physical and mental health benefits. This streetscape project is as much about the equitable enjoyment of public space as it is about improving commercial activity.

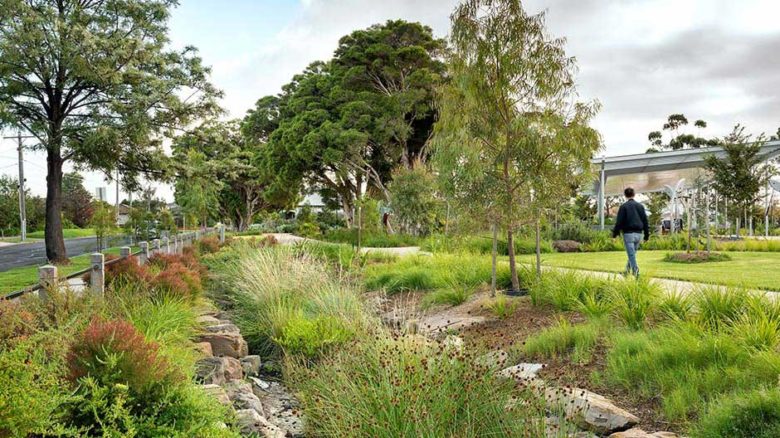

This year’s AILA Victoria awards also recognised regional urban landscapes. An urban design masterplan by Hassell to transform Wangaratta’s railway precinct, focused on providing attractive pedestrian links for locals and a welcome for tourists. It imagines a generous gateway experience of public space as shaded green infrastructure “at once logical and visionary”, also rethinking and transforming the urban centre through its connections to public transport.

An Excellence Award for Urban Design was given to Oculus in the ACT for imagining a future for a diverse community in the Braddon Precinct Place Vision and Strategy. Although not explicitly focused on pedestrian experience, it is evident from the strategy’s visualisations that walking is core to its vision. As the jury noted, Braddon is distinct from Canberra in the unplanned growth of its post-industrial neighbourhood, setting the team a paradoxical challenge: “How to employ urban design to understand, protect and enhance the authenticity of the place as it evolves towards a higher density, mixed-use neighbourhood?”

The answer appears to lie in streets that are far more generous to people than cars.

Union Road footpath upgrade for Moonee Valley Council.

Union Road footpath upgrade for Moonee Valley Council.

Wangaratta Railway Precinct by Hassell

Turf wars: Putting cars in their place

Conflicts between pedestrians and vehicular traffic have a long history. The concept of illegal jaywalking emerged in the 1920s in America, when automobile interests lobbied for a transition from blaming cars for hitting people to blaming people for walking where cars drive. Jaywalking is almost unknown in Europe and, until recently, little called out in Australia. America is seeing those laws used increasingly to target people of colour in a culture that frequently profiles pedestrians as poor. Streets are always political.

Just beside RMIT University’s Building 100 at the top of Swanston Street, Melbourne, a timber-slatted circular ‘bench’—or squash-spread bollard?—makes for a witty and good-looking vehicular snub. The Victorian jury gave landscape architecture studio Openwork an Award of Excellence, noting it “is a beautifully articulated urban solution to an increasing area of risk mitigation”—which is to say, stopping weaponised cars from killing people. Interestingly, Openwork were careful to advise that they were less interested in designing a bollard— that symbol of the age of defensive architecture—than creating “a land-form that invites the body to use it” and “makes a public space of invitation rather than exclusion.”

An aerial view of Openwork's circular installation at RMIT Building 100.

RMIT Building 100 urban solution by Openwork.

Braddon precinct footpath by Oculus.

Braddon precinct footpath by Oculus.

Campus expansions and redevelopments over recent years have also highlighted their role in contributing to civic life through their public-spirited pedestrian inclusiveness. A key factor in the award success of the Australian National University Acton Campus Master Plan and Design Guide by Arup is its “prioritising pedestrian movement over cars and parking.” The jury praised “reorienting the streetscape network, bridging divisive motorways, reopening creek and lake side connections” that all enable better and more enjoyable walking.

Kambri, a precinct delivered for the Australian National University, received an Award of Excellence for ASPECT Studios in association with Lahznimmo Architects. Community gathering—both town and gown—is facilitated by clear, directed access to a revived heart for the campus, free of vehicles. The name was gifted to the university following extensive consultation with local elders, adding to the inclusive thoughtfulness of the space. The jury noted that “axes are evident and celebrated, and their legibility and accessibility dramatically improved by lifting the University Avenue ground plane.” The graphic strength of the design continues a tradition of broad, tree-lined pedestrian avenues or malls, originally the term for a ground where pall-mall (a type of croquet) was played, that came in the 1700s to describe a long, tree-lined park where people went to saunter and socialize. Traversing the mall carries a sense of easy grandeur, quite different to strolling its crossing paths and unlike everyday walks.

Acton Masterplan delivered by Arup for the Australian National University.

Pedestrian Bridge as part of the ANU Acton Masterplan by Arup.

The water walk as part of Arup's ANU Acton Masterplan.

Circuits that connect us

While ANU’s Kambri boldly draws people to the campus heart, the New South Wales AILA Awards jury granted an Urban Design Award of Excellence for Darling Square by Aspect Studios for its network of niftily-detailed pedestrian connections. The jurors recognise its skill in “relinking formerly separated parts of the city.” Located on the site of the former Entertainment Centre, the square and its complex of pedestrian laneways, bisected by Tumbalong Boulevard “is held together by a simple yet strong spatial arrangement that addresses various built and open space interfaces with skill and meaning.” The rejuvenation has brought together diverse users circulating from Darling Harbour to Central Station, Ultimo and Chinatown.

Sydney’s Central Park Public Domain, by Turf Design Studio with Jeppe Aagaard Andersen, is a space that similarly connects diverse areas. The project also won an Urban Design Award, with the jury’s citation noting how it “subtly addresses each of its urban edges… stitching it successfully into the City fabric”. Developed on the site of the former Carlton & United Brewery, it is bounded by very different scales and eras of architecture, including the new One Central Park residential towers, existing workers cottages, terrace houses and the former C&U building. The design team envisaged “an expanded and interconnected network of new places—streets, lanes, parks and plazas; each unique yet forming a whole greater than the sum of its parts.”

Kambri, a new precinct for ANU, by Aspect Studios.

Central Park Public Domain by Turf Studio.

A skatepark as part of Sunvale Community Park by and for Brimbank City Council.

Council walk as part of Sunvale Community Park by and for Brimbank City Council.

Excellence in parks and open space was recognised at Sunvale Community Park by Brimbank City Council north-west of Melbourne. The park’s cross-cut figure-eight circulation paths draw on the classic urban park principles exhibited by Britain’s first municipal public park and inspiration for Frederick Law Olmsted’s New York Central Park, the Derby Arboretum. Along with its carefully landscaped walkways, the Arboretum had included minor structures and ornamental features for public gathering, delight and edification, much as public parks do today. In particular, Brimbank City Council noted that Sunvale offers the local community a place for walking, exercising and connecting to nature during COVID-19.

The AILA state award winners so far this year demonstrate that urban centres need our attention. They benefit economically, socially and culturally from enabling more thoughtful sharing of busy public spaces. Next week, we consider the more intimate pleasures of walking, looking at award winning projects that have helped us notice and learn from the world around us through art, the immersive experience of long walks and the neglected delights of feeling what is underfoot.

Dr Jo Russell-Clarke is a registered landscape architect and Fellow of the AILA. She is Foreground’s editor-at-large and a senior lecturer at the University of Adelaide.