Bamboo rising: Vo Trong Nghia reimagines an ancient ‘green steel’

Bamboo has surprising compressive and tensile strength but is also deceptively complex to use. Vietnamese architect Vo Trong Nghia navigates this complexity to create an architecture of connection and belonging.

This article is part of our Living Cities special series, in advance of the 2022 Living Cities Forum on 21 July in Melbourne. It is made possible through the support of the Naomi Milgrom Foundation. You can buy tickets here

Bamboo has been used in construction for thousands of years in a wide variety of cultural, geographic and climatic settings. It has been a key component within vernacular architectural traditions because of its local availability, rapid rate of growth, unique structural properties, and versatility as a material for construction and use in everyday life. This ubiquity as a construction material is perhaps also due to there being more than 1400 species of bamboo that grow in a wide range of climates centred on the equatorial belt, from colder climates of Japan and China to the warmth of Vietnam, Indonesia, South American and Africa.

The arrival of more durable standardised industrial products, however, led to the displacement of bamboo within communities with a history of bamboo use. In many developing countries bamboo is now regarded as a ‘poor man’s material.’ The celebrated Colombian architect Simón Velez explains this association, noting that ‘natural materials mean poverty,’ and ‘we have to show the world we are a civilized country.’ Construction in concrete, brick, steel and glass is prioritised and connections to vernacular culture and bamboo traditions are negated.

Challenging this view, Velez built a career pioneering new bamboo construction techniques catalysing a new wave of contemporary bamboo buildings by architects and designers. Velez redefined the scale of bamboo architecture through works such as the ZERI Pavilion for the Hannover World Expo in 2000. The pavilion demonstrated to the world the potential of bamboo as a modern construction material. Taking advantage of the structural properties of round pole bamboo, Velez developed new structural systems that celebrate the characteristics of bamboo and make a virtue out of the complexity of material irregularity. This has dramatically altered the social perception of bamboo as a ‘poor man’s material,’ celebrating its material characteristics through inventive forms.

In recent years Vietnamese architect Vo Trong Nghia has followed in Velez’s footsteps, employing intricate geometry to transform this naturally abundant material into expressive structures. He is one of a number of contemporary architects whose use of bamboo has led to it becoming a material celebrated as ‘green steel’ highlighting its sustainable, structural, and social benefits. There is, however, a paradox in how we understand bamboo. It is widely thought of as a simple material that grows quickly, is easily renewable and can be used unprocessed, but this belies the complex realities of employing bamboo in contemporary construction.

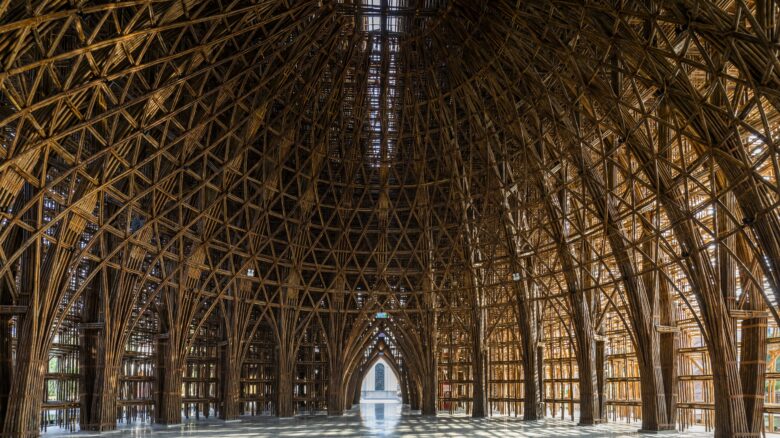

The modular and bracing nature of the framing increases the building's transparency and allows it to naturally ventilate. Images: Hiroyuki Oki

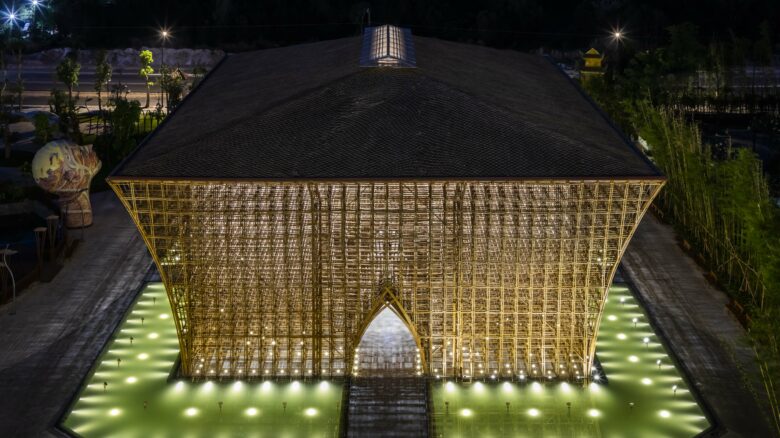

GWPQ Welcome Centre by Vo Trong Nghia.

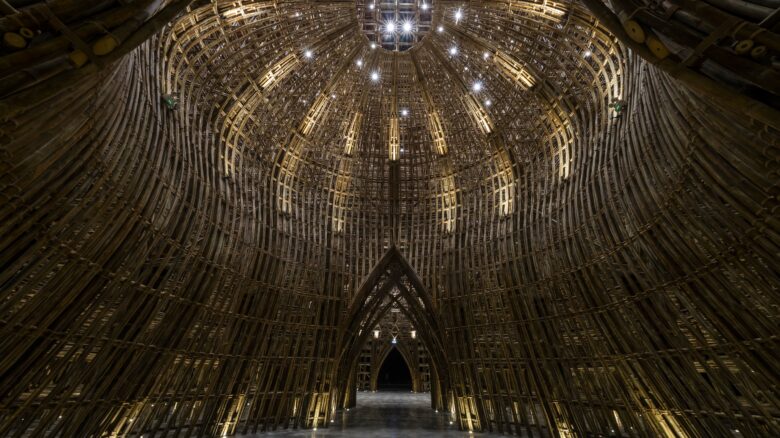

The GWPQ Welcome Centre by Vo Trong Nghia.

The GWPQ Welcome Centre by Vo Trong Nghia.

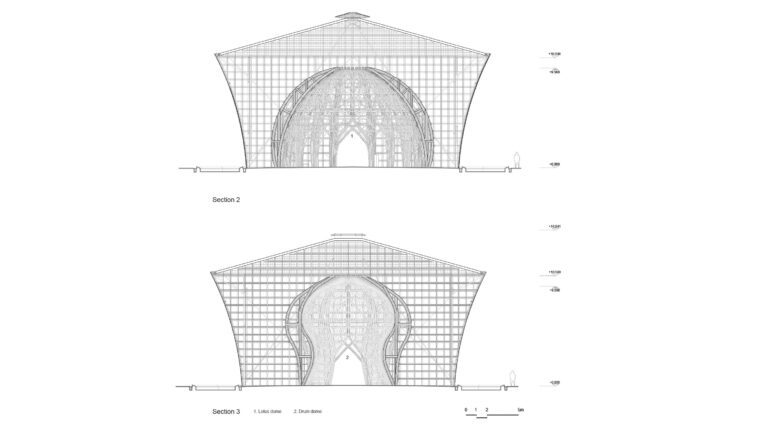

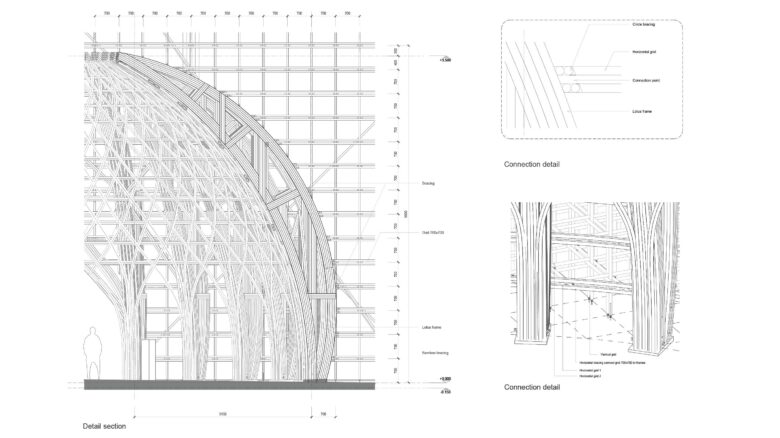

The drawings reveal a lyrical and elegant use of material, while also demonstrating a standardised and repeatable construction system.

Drawgin of the GWPQ Welcome Centre by Vo Trong Nghia.

Bamboo is a grass and unlike trees regrows after harvest. Different varieties grow at different rates, some as quickly as nearly a metre per day. The cylindrical culms can range from 15 metres in length and 15 centimetres in diameter in some species, to smaller and thinner canes. Species suitable for construction can be harvested in a three-to-five-year cycle. The tensile strength of some bamboo is greater than steel and some have compressive strength greater than concrete. It also has a range of environmental advantages, absorbing carbon dioxide and releasing oxygen at a rate higher that trees. Bamboo root systems prevent erosion and help to raise the water table, which can benefit adjacent crop fields.

While the benefits of bamboo are often discussed at a macro scale, challenges arise when working with bamboo at a micro scale. Untreated bamboo is highly receptive to water, fungi and insects, which reduces its lifespan to two-to-four years. Treatment processes are complex. Traditional treatments involve soaking in water or mud for several months, which changes the chemical composition and makes it inedible for insects. Contemporary treatments require soaking in boric acid or a more a toxic bath of copper and arsenic, which can leach into soils. New research is now emerging into treatment using nanocarriers in coatings and nanosized compound penetration to improve anti-microorganism capacity, thermal stability, flame-retardant properties and ultra-violet resistance, but such treatments are complex and expensive.

Vo Trong Nghia's Son La Ceremony Dome. Image: Hiroyuki Oki

Vo Trong Nghia's Son La Ceremony Dome located in Son La city, Vietnam. The domes have a double layered structure that is punctured to allow natural lighting and ventilation. Image: Hiroyuki Oki

Vo Trong Nghia's Son La Ceremony Dome.

Vo Trong Nghia's Son La Ceremony Dome.

Even when treated, bamboo requires protection from water and sun, with the rule of thumb that bamboo buildings need an overhanging roof (hat), footings that keep bamboo out of water (boots) and protective coating (coat). Round bamboo culms require specific jointing techniques, and as no two culms are the same the material irregularity presents challenges for design and building certification. Efforts to standardise bamboo into a consistent product have sought to solve technical issues, such as treatment, grading, material and construction standards, fire resistance, processing, jointing and connections, mechanical properties, and ecological impact.

Many of these issues are addressed by processing bamboo into manufactured bamboo products with standard dimensions and material qualities. However, this process transforms bamboo into a laminated product, which has entirely different physical, mechanical and environmental properties to round pole bamboo, and eliminates its unique material characteristics.

Vo Trong Nghia’s architecture demonstrates the potential for the innovative use of unprocessed bamboo in contemporary architecture. Vo and his team began experimenting with bamboo structures in the Wind and Water Café and Bar in 2006, developing structural systems that work with the characteristics of bamboo and draw on Vietnamese cultural symbols to create associative connections through inventive new forms.

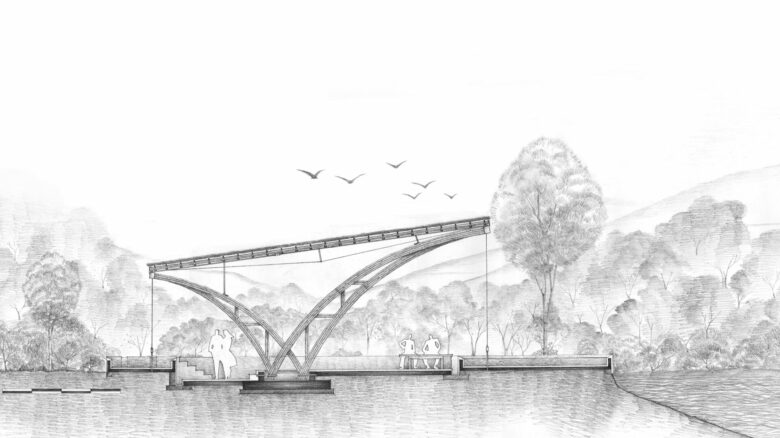

Over the last 14 years the practice has created a range of innovative structures inspired by traditional baskets that weave thin elements together to form a light and strong structure in which one element can fail without compromising overall structural integrity. Scaling-up this idea, individual bamboo culms are ‘knitted together’ and standardised bamboo modules are created to form long-span structures. Bundles of bamboo are bent into arches and finger joints pinned and bound with rope. Low overhanging eaves protect the structure from sun and rain and create a strong contrast to the towering internal domes.

Bamboo Wing interior. The curved bamboo frames were created by heat treatment.

Bamboo Wing is a cultural centre that holds local events such as fashion shows, live music and conferences

Bamboo Wing section drawing

The bamboo was soaked in mud and then smoked, to ensure the bamboo is antiseptic and mothproof. This also contributes to its rich, lustrous finish.

Vo calls for architecture to ‘transform itself from a source of pollution to a reason for hope.’ He believes that that people have an ‘innate fondness for the natural world’ and that our attachment to places is a key aspect of durability. This is particularly important, he argues, in rapidly developing countries that are undergoing an ‘untenable cycle of destruction and construction‘.

His architecture employs forms that are designed to complement the landscape, mirroring the distant hills, or draw on cultural symbols like lotus flowers, drums and baskets to create arches, domes and grid systems. Passive strategies are employed to generate wind energy and draw on evaporative cooling to create natural air-conditioning. Vo uses traditional techniques of soaking bamboo in water for several months and then smoking with rice husks for two weeks, which dries out the bamboo and replaces oils lost during construction, giving a ‘polished earthy, yet shimmering appearance, a simultaneously traditional and modern aesthetic.’

So far, Vo Trong Nghia’s bamboo projects are primarily pavilions and small structures for tourism and cultural uses, rather than everyday domestic or commercial buildings. However, they draw on the diverse and unique material properties of bamboo to create inspiring and uplifting places that connect people to place and culture, past present and future. This in turn points to a wider question beyond bamboo. What other widely available and undervalued ‘poor man’s materials’ might be transformed into an architecture that is cared for and valued?

—

Vo Trong Nghia will be speaking at the Living Cities Forum on 21 July 2022 at Melbourne’s Federation Square.