Finding life in places for the dead: The future of cemetery design

In Melbourne’s west a 128-hectare site represents the largest cemetery development in Victoria for 100 years. But rather than just planning graves, the vision for Harkness Cemetery includes creating green space for its community.

The cemetery in Harkness, a new suburb in Melbourne’s City of Melton, is remarkable for more than just its vast size. The Greater Metropolitan Cemeteries Trust, the cemetery’s managing body, hopes it will become a space with a multitude of possible uses beyond burial and memorialisation.

In the conversation that follows, Katrina Simon, RMIT University’s Associate Dean of Landscape Architecture, talks with GMCT design manager Hamish Coates about the history of cemetery design and why Harkness Cemetery will be as much about designing for the living as it will be about commemorating the dead.

Katrina Simon: Hamish, first of all, can you explain what your role exactly is?

Hamish Coates: I’m the manager of a design team at GMCT – we call ourselves ‘future design’. We sit within the directorate of Future Built Environment, recently formed in recognition of the fact that we’re building more than just cemeteries and that this requires a broader landscape-based approach to cemetery design. We want to create spaces that go further than building graves and filling them up.

Our approach treats cemetery spaces the same as you would any other landscape. That is, applying landscape-design principles and measures, such as access, resources use, identity, community, sustainability and culture.

We have a planning team that works out the budgets and the program in conjunction with discussions about design and construction. And once that’s established, it gets handed over to me and my team. We proceed to either design it in-house or outsource it. We then hand it over to the construction team.

For an organisation like GMCT, which is quite conservative and risk-averse, proposing design ideas must be done very carefully. The executives are comfortable with a landscape architect designing a suite of graves for a site – that makes sense to them because they can see a constructed output at the end. However, the strategic planning aspect is a long-term undertaking where the vision can easily be lost.

KS: So have the agendas that you’ve been trying to design around – sustainability and public use – been matched with a change in what the broader market wants from cemetery spaces?

HC: The tricky part with designing public places is the need to include the community and engage with them. It’s tricky because as a professional with a studied understanding of the site and a design expertise about what you think should be done, this can often be counterintuitive to the wishes of the community and other stakeholders.

I’m happy to leave that decision to others with more consulting expertise. However, communicating new ideas and approaches in a traditional and historic space needs to be carefully measured. Particularly with shifting cultural attitudes towards the future role of cemetery spaces. Consultation and engagement are important and need to be handled with sensitivity.

The other aspect is that cemeteries are vast open spaces. They serve a purpose for a range of visitors and not necessarily those who are grieving. So what can we do with these spaces?

With a greenfield space like the Harkness site, it’s quite easy. We can set the tone from the beginning by applying a vision. But with existing cemeteries, there’s another thought process that we have to deal with. At the moment, it’s really just a question of starting those discussions with executives and shifting the culture within the organisation.

KS: Have your ideas about cemeteries changed a lot since taking the job?

HC: Yes, I’ve become more educated about them and my ideas have become more refined.

I got involved with cemeteries when I was running my own business several years ago. I was phoned up by a landscape architect called Paul Laycock who was running his own practice. He had a couple of cemetery projects that I helped him draft up and it went from there. He got me started in cemeteries and that got me more interested in them.

When I started with GMCT, I was really just thinking about space and laying out graves in cemeteries. But then I thought, what else can I do with this space? From that question all the landscape principles became evident and my approach evolved.

Fast forward to Harkness, which was on the books at GMCT and in desperate need of a master plan. I’d done a master plan for Southern Metropolitan Cemeteries Trust’s western site and I took some ideas out of that and flipped them over into the [Harkness] site at Melton. At that point those were good ideas that were effectively sitting at the bottom of a drawer.

We put those ideas forward to the board and they got very excited about exploring the potential of what cemeteries could be. At the time I was one of only two landscape architects in the organisation. I was bright eyed and bushy tailed. I wanted this to be a blank canvas for what ideas we could pursue.

KS: Of the ideas presented to the board, which was the most critical and well received?

HC: After landscape architecture I went to art school – not because I wanted to become an artist, but because I wanted to become a better landscape architect.

So I looked at this blank canvas and thought, how can we inject some meaning into this proposal through an artistic approach?

The master plan for Harkness was centred around the DNA double helix. As a motif it helped to drive the two strands of the design development: a cemetery and a park. Using this structure in a modular way also created a framework to inform future development of the cemetery, preserving the design’s integrity.

The double helix motif also reflected a kind of metaphor for life.

When you lay out graves in a graveyard or a cemetery, it’s like a housing development – it’s faceless. The idea was to inject some personality and individualism. To preserve the memory of each person. The idea underpinned the cemetery space by having some sense of individualism expressed through referencing genetics.

KS: There’s a wonderful book, The Hour of Our Death, by Philippe Ariès. It’s a great sweeping history of death going right back to Roman times and covers ideas in the western tradition that we’ve largely inherited. He wrote about the emergence of the sense of individualism in the west and how that corresponded with a change in the way that graves were identified.

To begin with, in early Christian times, graves weren’t really identified and sites were often very volatile. People were buried for decomposition then the bones were removed and then more bodies went in.

It was much more in the mix of life than it is now. We would be horrified with germs and disrespect and all those sorts of things today. But it reveals how over time different aspects of that individual life became important to record. So first it was the date of death recorded, then it was their birth and death dates, then their families, then what the deceased’s occupation was. And the recordings became much more distinctive over time.

One argument attributed to this is that from the 17th century onwards this trend reflected a private loss of belief in the afterlife, even if publicly people were still obedient to religious tradition. Instead that was matched by an overemphasis on things in the world that the deceased could be remembered by.

HC: That’s an interesting notion because I don’t know where the concept of family came from, in that respect. The concept of family was a very individual idea. When we design cemeteries, it’s all about how the family can come and grieve. We also design our cemeteries so that more than one person can be buried in the same plot, presumably a family member.

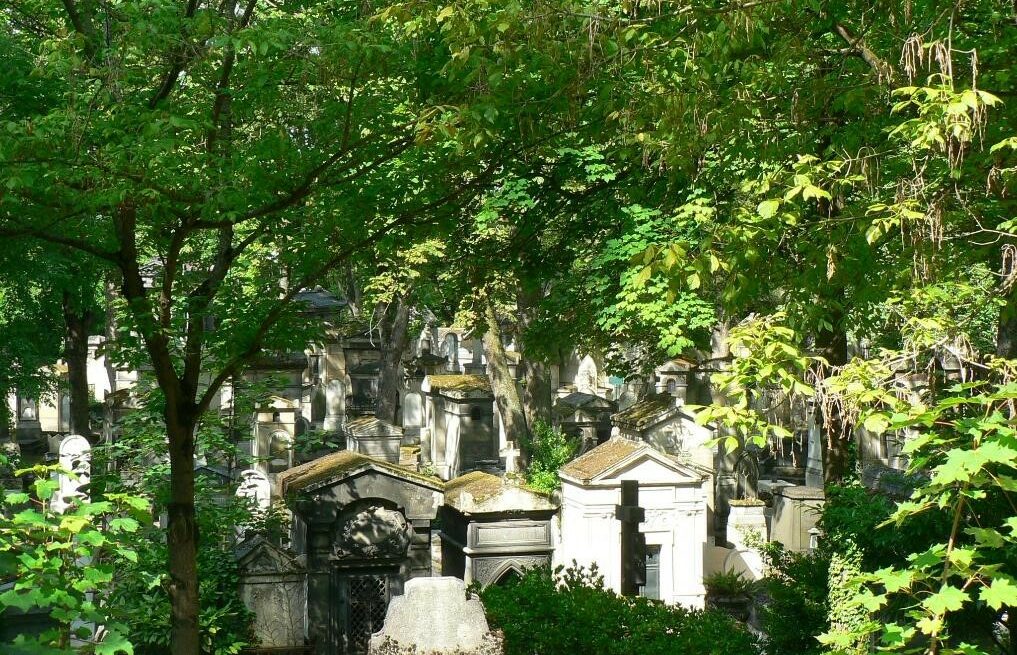

KS: In the late 1800s, Parisian cemeteries were where much of this cemetery reform occurred. This was really where we saw these ideas of rest, stasis and perpetuity begin to take hold. But if you look at the cemetery at different scales and time periods, it’s really all about movement. In the cemeteries themselves the bodies actually moved around.

It was in the great early 19th-century cemetery Père Lachaise that a grave could be owned as a piece of property, in perpetuity, for the first time. Up until then, (in western Christian societies) you were basically in the care of the (Christian) church until Judgement Day when you would need your body. So that’s why the bones were important.

In the late 18th century, there was growing concern around these huge cemeteries in the centre of Paris because of diseases and the plague. A law was passed and all the cemeteries within the city walls were closed. They had to move to the outskirts of the city, which really took it back to the situation in Roman times when cemeteries were outside the city. Over a period of about three years, all the remains were relocated, dug up and put into the catacombs – old gypsum and stone mines. They needed to keep the bodies for Judgement Day. You had to have something to rise up in.

Père Lachaise was originally a private business. And to make it more attractive, they disinterred and reburied some famous people as public attractions, including some famous mediaeval people.

One couple was Abelard and Hélöise: he was a teacher of philosophy and theology, and later a mediaeval monk, and she was his pupil. There’s more to this story but in short they had a great love affair, died at different times and would eventually be re-buried together in Père Lachaise.

Also in mediaeval times, the rich, especially if they were travelling with the court or with nobles, would list in their will where and how the different parts of their body might be buried in different places. For instance, the head in one place and the heart in another. Sometimes parts could be buried in up to four different places.

HC: That’s very interesting because it’s a long and detailed process to exhume the body and relocate it now. It’s a really emotional and multilayered thing to do. If you buy a piece of land, as soon as you bury a body in it, if you’re legally allowed, it devalues completely because you can’t easily exhume the body.

From a fiscal point of view, the value of that land becomes almost worthless because it has a body buried on it. But obviously it has other value. I think people understand that burying bodies take up space, but not the effects that it has on the continuing need to find more space, which is a very challenging process. That’s a question we wrestle with at GMCT – how do we deal with land? It’s such a big question.

KS: One of the issues facing a great many Victorian cemeteries, especially older ones, comes from this tension between perpetuity and the availability of space. Cemeteries are filling up and plots are maintained for an indefinite amount of time. Is there renewable tenure of grave plots in Victoria and how does time play into these landscapes?

HC: No, in Victoria burials must be preserved in perpetuity – known as Right of Interment – which means the purchase of your grave must last forever. But this is an issue that’s becoming more frequently discussed because we have to confront it at some stage.

The conversation is more often focusing on renewable tenure as an option to reuse grave plots and return burial space back to the market. We have several existing sites that are filling up and transitioning to perpetuity. Meaning they’ve reached capacity and will require ongoing maintenance to look after them indefinitely.

What can we do with these places? Can we retrofit social and recreational aspects to cemeteries so that they can contribute to the community in a more constructive way, rather than solely be a place that contains graves?

KS: Have you been to the Waikumete Cemetery in Auckland? It’s a really wonderful cemetery. It’s very large and extensive, and many parts have an incredible vista over the city and out to the Waitakere Ranges.

Waitakere has a very green council and really pushed the environmental agenda. They re-did the environmental assessment for landscape quality and for vegetation rarity. And this particular landscape where Waikumete Cemetery sits is in an area that used to be kauri forest.

But they were all logged and then the ground was dug over for gum, as the resin from the trees was used for varnish. The whole process basically left the soil very impoverished. And so out of that, a very unusual combination of vegetation evolved together. Through this council process of re-evaluation, the cemetery’s ecologies were deemed to be very rare and overnight about 80 years of its life were eliminated — the council said “you can’t build there”.

I was involved in several design studios when I was teaching in the Landscape Architecture program at Unitec in Auckland where we looked at reusing parts of this cemetery. But also to see if we could assist the area to thrive and incorporate remains in different ways. It was quite an interesting case study as it opened up ideas of how different types of vegetation communities and graves could potentially co-exist.

HC: That’s interesting. At one of GMCT’s western cemeteries in Truganina we can’t use around 90 per cent of the site because it’s an endangered native wild grassland. So it’s facing similar conservation constraints to be worked around.

The Department of Environment, Land Water & Planning have now taken over the management of that aspect. But previously it was maintained every couple of years through burning the grassland. I haven’t been there in a couple of years, but it was quite a crazy landscape. It’s a classic grassland and quite remote. But I suspect now it’s sadly being swallowed up by housing estates.

It also calls to mind a work from Nelson Byrd Woltz – the Naval Cemetery Landscape in Brooklyn, New York. It’s a very small historic cemetery. They couldn’t disturb any of the ground, so they developed a circular and curving boardwalk on a pile drive structure and then seeded it with pollinating species from the local ecology.

For me it ticked just about every box of preservation, conservation and cemetery design. And it looks exquisite. The idea behind it was to preserve the graveyard but to give it life through supporting ecologies.

KS: I visited Rarotonga years ago, a volcanic Pacific island. What’s amazing is that the tradition there, the land ownership structure, is very different.

It’s not one person, one ownership, but a complex family ownership structure. I don’t understand enough of the details at all. But people are buried on the land. So there are graves everywhere and they’re beautifully cared for, like a little home, and decorated. It creates a very different environment. It’s almost like an acknowledgement of the whole life cycle. Which is a really healthy approach.

HC: It’s such a closed conversation. I think that’s the reason why I like the fact the state government amalgamated the cemetery trusts. Because prior to that, no one really knew about them, they were just doing their own thing quietly, secretly. And I think, by the same token, that’s because no one really wanted to know about them either.

I think that attitude still prevails because there’s an idea that we don’t talk about people dying because we can’t celebrate that like birth. That, to me, is something that we want to try and change through cemetery design.

Postscript: In September 2021, GMCT announced that a consortium of Aurecon, Architectus, McGregor Coxall and Greenshoot Consulting will develop a master plan for the greenfield site at Harkness. Click here to read more about their plans.

–

Katrina Simon has particular research interest in the history and design of cemeteries and the ways in which they evolve and change. She is currently the Associate Dean of Landscape Architecture at RMIT University in Melbourne.

Hamish Coates advocates for cemeteries to be developed as positive community assets. Hamish is a registered landscape architect and leads the design team at the Greater Metropolitan Cemeteries Trust and chairs the cemeteries committee for World Urban Parks.