The Green Necklace: a new perspective on Sydney Harbour’s parklands

Many of Sydney Harbour’s built structures are heritage listed but the landscapes that give the Harbour Bridge and Opera House their power are not recognised for their cultural significance. A timely study of the harbour’s “green necklace” of cultural landscapes looks to change that.

Of the recent big-picture winners of the Australian Institute of Landscape Architects (AILA) New South Wales (NSW) awards, one project stands out as particularly ambitious. Challenging how we even conceive of landscape, the AILA (NSW) Landscape Heritage Conservation Listing Project provides a framework for us to reexamine, reflect on, articulate and value cultural landscapes. In views crowded with famous structures, the project helps us see and appreciate the significance of Sydney Harbour’s parks, gardens, open space and remnant bushland.

Sydney Harbour’s Green Necklace

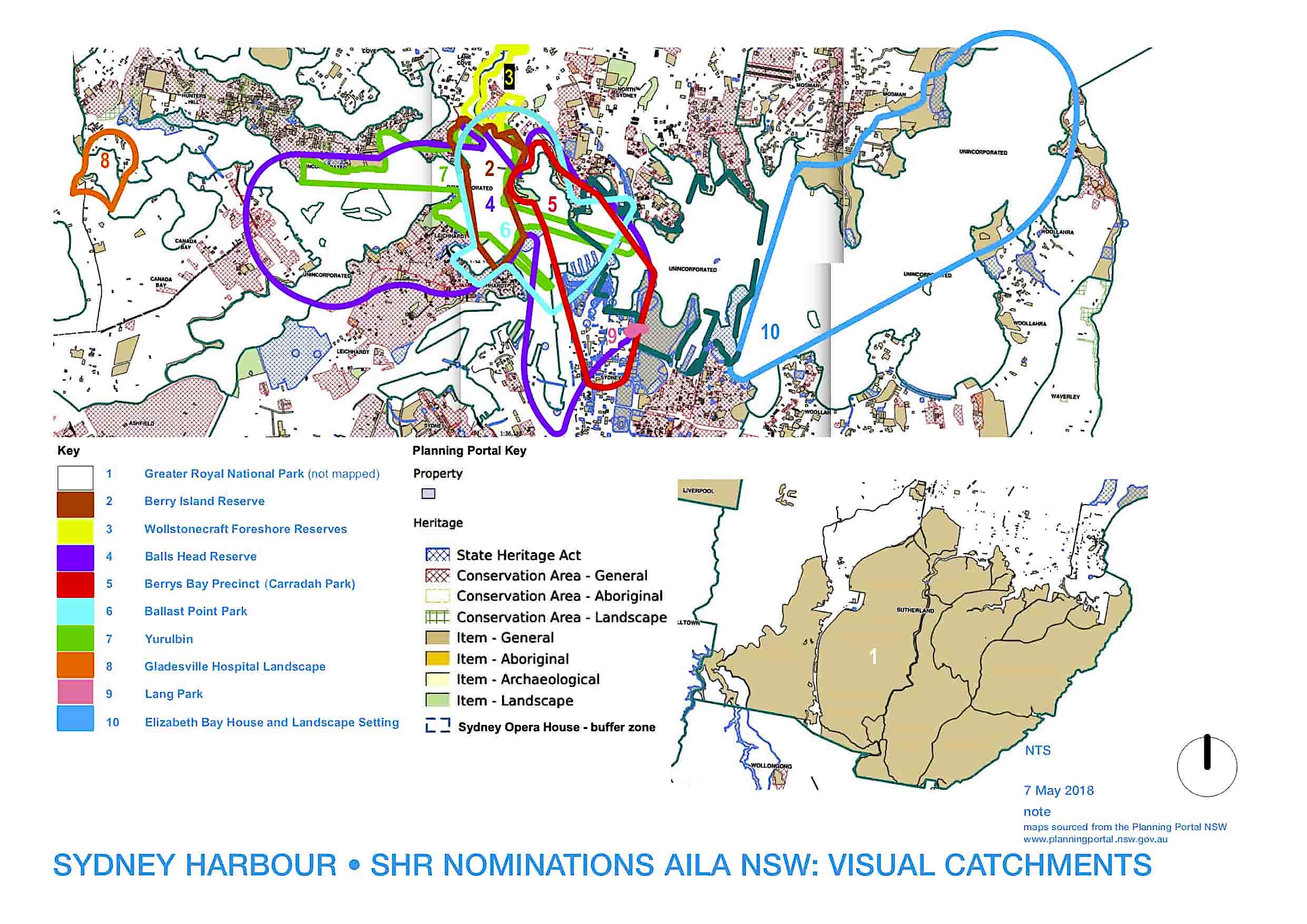

A specialist team comprising registered landscape architect Christine Hay, landscape heritage consultant Colleen Morris and registered architect James Quoyle have received an Award of Excellence at the annual AILA NSW awards. All three also have heritage conservation qualifications. Their study of the cultural heritage of assorted green spaces ringing Sydney Harbour included “parks, government institutions, Crown land, fragments of open space and remnant bushland, linked to create the ‘Green Necklace’’. Their project – The AILA NSW Landscape Heritage Study – has also received a National Trust Heritage Award for Landscape Conservation. The work developed a ‘landscape lens’ method focused on a whole-of-landscape approach that looked beyond the limitations of cadastral boundaries to include visual and water catchments as part of the shared heritage value of significant landscapes.

Sydney Harbour is one of the world’s great harbours. Its shores are dotted with iconic structures including the Sydney Opera House, and are linked by another icon, the Sydney Harbour Bridge. These structures and many more are heritage listed, but it is arguably the harbour itself that lends them their power. However the landscape – the land and water of Sydney Harbour – is not as a whole protected. This project set out to offer improved ways to consider and gain such recognition for important landscapes. As explained in the first volume of the study: “In the past the SHR listing process evolved from a fabric-based approach which focused on significant built elements with landscape as a setting. What is required is to invert the process where landscape is the significant item with the important built structures as elements within and responding to it.”

Securing heritage recognition and protection for places takes time. As well as the time needed to develop detailed reports there is the process of assessment. It can take many years, working with many people, including owners and custodians, to understand and document the values of a place. Christine Hay and the team were working with a grant awarded by the Heritage Council, administered by the Heritage Division of the NSW State Government. The grant was to research and develop applications for ten sites of landscape heritage significance for the NSW State Heritage Register (SHR), increasing the number of landscapes listed as well as overall appreciation of landscape values and a method to better enable future nominations.

While the SHR criteria for listing allow for recognition of landscapes as significant heritage sites for, among other reasons, their ‘natural’ history and environmental values, an early workshop with landscape architects and heritage consultants, for the study found that many practitioners believed landscapes were not well represented in the SHR list and that their significance was not sufficiently appreciated or understood. Even though visual assessment and mapping of views are well-documented planning tools, it is unusual to include water within a proposed heritage area. Hay, Morris and Quoyle considered the waterplane of Sydney Harbour in their review of potential sites for heritage listing, and concluded to add adjacent waters in their final ten nominations. The result is a series of landscape gems forming an interwoven ‘green necklace’ around and across the harbour.

Talk to stakeholders beforehand

Hay acknowledges the importance of working closely with those in government and elsewhere who can help guide and develop reports to most effectively produce successful nominations. The team’s process included early meetings with the NSW Office of Environment and Heritage (OEH, now Heritage, Department of Premier and Cabinet) and the AILA NSW Chapter, Landscape Heritage Group (ALHG) amongst others. “Step by step we brought all our thinking together,” explains Hay. “A nomination for heritage listing comes from the community, in this case the AILA” says Hay “and we feel our nominations are quite strong because we had already worked so much with stakeholders and government.”

Consultation and collaboration formed an integral part of this pre-working process. The team’s award submission acknowledged the ALHG (Matthew Taylor (Chair), Helen Armstrong, Craig Burton, Oi Choong and Annabel Murray)and staff from North Sydney Council, Aboriginal Heritage Office, Property (NSW), as well as officers of the OEH as collaborators. Hay remembers in particular how helpful Christina Kanellaki Lowe of OEH was in seeing beyond the site to a wider landscape significance. Hay is hopeful for the listing of their ten nominated sites and is excited that Berry Island Reserve and Wollstonecraft Foreshore Reserves may be progressing toward SHR listing as one landscape.

Joining the Dots

Created in 1999, the New South Wales State Heritage Register (SHR), administered by the NSW Office of Environment and Heritage (OEH), contains over 20,000 statutory-listed items in either public or private ownership. But while there are sites listed on national and even world heritage registers they are not state listed. The (now) Royal National Park outside Sydney is Australia’s oldest national park and the second in the world. It was added to the Australian National Heritage List in December 2006, and is also listed by local government but is not on the SHR. The team documented a Greater Royal National Park as their first nomination for the register.

What is particularly interesting, yet difficult, is recognising a ‘site’ that is not clearly bounded. “Landscape is vast” explains Hay, and the team set an ambitious initial overview of possibilities for site listings. Undertaken over two and a half years, the study’s philosophy ‘the landscape lens’ evolved from a mapping resource identified by the ALHG. Its principles, in line with the Burra Charter, consider natural systems, spatial qualities, historical development and human responses to place.

“We started looking at landscape conservation areas” which are recognised as precincts in the Heritage Act 1977, “but the potential number of sites to assess in each was too big”. There was limited time and funding to develop the nominations themselves – which constitute Volume 3 of the report – but the preliminary work of the first two volumes which established and put into practice the ‘landscape lens’ will greatly assist future listing of significant landscapes.

The AILA NSW Landscape Heritage Study is a ‘heritage’ report, rather than an environmental or ecological report. But the protection and restoration of ‘natural’ vistas and landscapes is being recognised as a vital part of the effort to preserve the historic identity of urban places. As the heritage study suggests, a “major shift in thinking is required to recognise that landscapes themselves are an essential component of cultural heritage in addition to individually significant trees, buildings, gardens and archaeological sites.”

Heritage significance can and does lie in the natural systems and qualities of a site as much as social and historical association. There is an obvious logic too in recognition of environmentally distinct landscapes as also culturally significant – beautiful places inspire cultural responses, while natural materials, geology, flora and fauna are what social practices, economies and local settlement grows from and reflects. Aboriginal cultural heritage and history is one very important aspect of this that the team looked to draw more attention to.

For Hay the project speaks to understanding the bigger picture of the landscapes around us. Investigating and documenting this for heritage listing helps make this important interpretation available to people. “One of the main differences [about this approach to heritage] from my perspective is thinking about landscape as a catchment, which implies connectivity.”

A view of Berry Island with beach and water demonstrates the importance of waterscapes as an integral part of Sydney Harbour cultural landscapes. Photo: provided

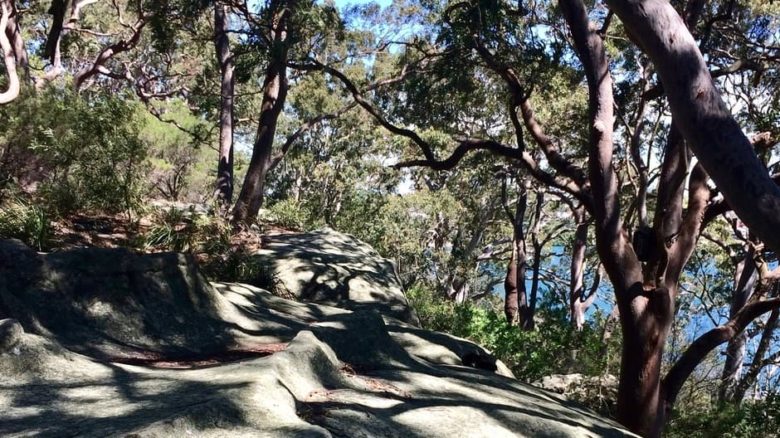

Sydney Harbour has a green necklace of open spaces with adjasent water views worthy of heritage listing as cultural landscapes. Photo: provided

A track around Berry Island in Sydney Harbour. Berry Island Reserve is one of 10 cultural landscapes nominated for heritage listing in the study. Photo: provided

Another key criteria of the study in pursuing significant landscapes for listing was to review the exemplary work of a passing generation of Australia’s first landscape architects. “Older practitioners are looking back at their legacy and wondering about the values of those times that are manifest in the work” says Hay. All forms of landscape are under threat from development, but more recently designed landscapes are even less regarded as potential heritage places than either natural environments or places of indigenous significance. Hay mentions Andrew Pfeiffer as one such practitioner of many. David Banbury, landscape architect and project manager from North Sydney Council works with the challenges of protecting heritage assets such as the landmark wharf at the former coal transport depot at Balls Point Reserve. Banbury recently highlighted the importance of the Coal Loader site as a community place that has come to represent the intersection of the old and new.

Small Triumphs in the Recognition of Landscape Heritage

The heritage value of cultural landscapes is already reflected in the SHR criteria, as it is in UNESCO world heritage values, and is part of what has made the Burra Charter so influential. The charter influentially acknowledged a range of values that were different to those evident for European historical monuments where heritage conservation was initially formalised. Hay and her team were grateful for their consultation with the Australia ICOMOS National Scientific Committee on Cultural Landscapes and Cultural Routes, responsible for the Burra Charter and its revisions.

This project follows in the footsteps of global measures to recognise less tangible, yet still demonstrably valuable cultural heritage. UNESCO provides an international listing of intangible cultural heritage which includes sounds, smells and practices as part of protected local legacies. Australia has no entry in this listing. Last week it was reported that France may legislate to protect rural noises, as tourists complain about noisy roosters, church bells, cicadas and farm machinery. As the news report notes, a territory’s identity is marked by its “landscape, flora and fauna [but also] more than what the eyes can see.”

Despite its importance, there is no national-level guideline for Landscape or Visual Assessment (LVA) in Australia. The Planning Institute of Australia will hold a workshop in October on this issue. Landscape architects in Australia have relied largely on documents from international landscape architecture institutes and government bodies. The Department of Premier and Cabinet has collated many local references and pursued research projects to provide practical guidance to land managers in the conservation of cultural and community landscape heritage. But, as suggested in a new book by former Chair of the Australian Heritage Commission Professor David Yencken, the richness of Australia’s national heritage listings has been an ongoing concern since our relatively recent start at conservation efforts.

The number of heritage nominations that make use of landscape values and recognise landscapes as heritage places is much lower than the more easily argued and defined aspects of built form and constructed historic objects.

“It’s a slow raising of awareness” says Hay who is encouraged that other AILA awards this year also looked to a bigger picture of landscape value. The next steps for the team include promoting further interest in the work. Their study has already piqued the interest of several local councils, keen to list and protect more of their local landscapes. At state level the team has met with Barbara Schaffer, Principal Landscape Architect in the Office of the Government Architect NSW and presented their work. Hay feels the work is part of an inevitable and welcome trend to a more mature, sensitive and richer inhabitation of our landscapes.

This year the AILA NSW awards recognised a number of very big projects with an Award of Excellence. The scope of the Western Sydney Parklands Design Manual by NewScape Design in collaboration with Western Sydney Parklands Trust, recognises the pressures and potential of the fastest-growing region in Australia’s biggest city. Similarly a massive new park was envisaged in the Southern Parklands Framework by Tyrrell Studio in Collaboration with Western Sydney Parklands Trust. The Sydney Water Waterway Health Improvement Program (WHIP) by McGregor Coxall is a major green and blue infrastructure project, while their Cooks to Cove GreenWay project connects the under-utilised infrastructure corridors of 108 hectares of remnant ecologies. The reference guide Everyone Can Play: A Guideline to Create Inclusive Playspaces is, by definition, an all-encompassing best practice toolkit of case studies and examples to assist in delivering playspaces for everyone. More awards were made to further ambitious, large-scale and long-term projects.

–

The legacy and future of Squares and Parks is the focus of this year’s International Festival of Landscape Architecture in Melbourne, 11-12 October.

ICOMOS 20th General Assembly and Scientific Symposium will be held in Sydney in 2020. The Green Necklace will be a central idea for the conference.

Christine Hay, Colleen Morris and James Quoyle are all members of the Australian Garden History Society (AGHS) whose conference will also be held in Sydney in 2020.