How the Royal Botanic Gardens Victoria is saving flora from climate disasters

Almost 26 million acres have burnt in Australia since November 2019. Enormous effort is needed to help bush recovery and to plan for future fire seasons. Foreground spoke with Tim Entwisle, Director and Chief Executive, Royal Botanic Gardens Victoria, about the Gardens’ vital and varied work.

Recent fires in south-eastern Australia have raised fears for the survival of more than 250 threatened species. But it’s not just animals under threat. Plants on which fauna depend are also facing extinction. And while there have been heartening reports of rejuvenation of blackened bush, there is much more to consider both in the ways we help the bush recover now, and in how we plan for a climate-changed future of intensifying challenges.

Surrounded by a temporary fence, the broken limbs of a white oak, over 150 years old, lie across the oak lawn at Melbourne’s Royal Botanic Gardens. It is almost the first thing gardens director Tim Entwisle mentions. One day, half the tree broke away. Even as the Gardens decided to invest in supporting and saving the remainder, the tree collapsed overnight. Yet the Gardens staff didn’t remove it immediately. Entwisle explains that this was partly about deciding how to manage the timber, but also because the tree would have meant so much to people that they may wish to come and see it. A sign explains the circumstances and invites visitors to share reminiscences.

The fallen oak features on a webpage that outlines how climate change is affecting the plants we grow. As Entwisle speaks about the many ways in which botanic gardens are helping with drought and bushfire recovery, he also reveals how conservation is not simply about preserving particular species or even ecosystems, but is a mission of care for the place you live in. Cultivating that care seems as much a part of the mission of the Gardens as its work with plants.

The Royal Botanic Gardens’ growing role in conservation and revegetation

The varied work of botanic gardens has many threads, from scientific cataloguing and research, to education, to visitor engagement with events and, of course, the maintenance of the public gardens themselves. All of these can play a role in helping communities deal with the challenges of a changing climate. In helping recovery after fire, The Royal Botanic Gardens Victoria offers two key services. The first is expert knowledge of plants and their habitats based on long study and the records of the state botanical collection held in the herbarium. The second is the Victorian Conservation Seedbank. It holds seeds of native plants of south-eastern Australia, presently about a third of the state’s flora and probably half its rare and threatened species. “We’ve recently had a very strong focus on alpine plants because we are worried, with climate change, that they may be the ones to go first,” says Entwisle.

Seed from the Victorian Conservation Seedbank includes a third of the state’s flora and around half its rare and threatened species.

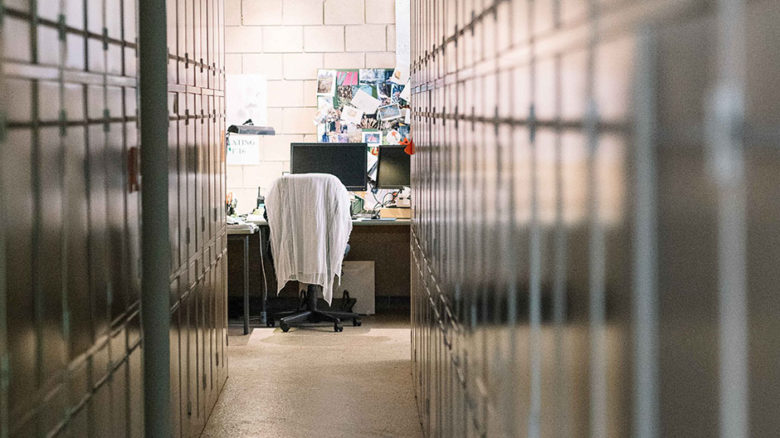

Volunteers help with mounting specimens at the Royal Botanic Gardens collection in the National Herbarium.

The National Herbarium stores the unique records of the state botanical collection and a wealth of botanical knowledge.

Following disasters such as the recent fires, the Botanic Gardens works closely with the Department of Environment, Land, Water and Planning (DELWP) to organise recovery. “DELWP lead the recovery, and we come in as a partner, bringing botanical knowledge and plant material,” Entwisle explains. “Over the last few weeks we have been meeting with the department, using maps initially to look at what impacts are most likely with different ecologies and what species might be under threat.”

The next step is to look at what might be done immediately to help species regenerate in situ, including “making sure that if there’s any clean-up to be done, that they don’t clean the plants up!” There are other general aspects to managing the post-fire landscape. “You don’t want to rake up all the ash and the nutrients that need to go back in the soil,” says Entwisle. “The other thing we do after the fires – and it seems slightly odd in a way – is go out and collect seed.” Over the coming months and the next year or two, many plants will produce seed. Collecting seed from a variety of sites builds up ‘insurance’ against biodiversity loss with future fires.

In areas of dry forests where the flora has adapted to survive fires, many species will return. Some hold seeds in the canopy, Banksias hold seed in their fruit until a fire, ground orchids are protected by most fire because they are underground. But if the fire is too intense, even these bake, and if fire is too frequent they won’t get a chance to produce seed and reproduce. The recent Victorian fires also affected about half the region’s warm temperate rainforest, which does not usually burn.

Climate change predictions are that we will have more severe fire, extreme wind events will be more frequent and temperatures will be higher. “We know in our garden environments, for example, that we will have more days above 35 degrees and that is quite dramatic for us,” says Entwisle. Aside from the one or two degree overall average increase, it is such extremes that pose problems for plants. In terms of managing natural vegetation and our forest assets, Entwisle sees what we do to landscapes outside fire seasons as vital. “There’s a big debate going on at the moment about controlled burns,” says Entwisle, adding that the scientific evidence is that controlled burns are part of managing the forest. “But they are not the answer to everything.” Pre-burning all vegetation and continuing to burn it over and over ignores the reality that individual ecosystems need different fire regimes. “It’s the nuance in that debate that I hope we can contribute to.”

The Garden’s seedbank is a long-term strategic response to climate change and future revegetation. But if climate change means that the conditions for certain species are shifting or shrinking – as Entwisle fears for Australia’s alpine species – what can be done? The movement of plants across the landscape is a vexed question for Entwisle. “Do you reclaim back land to allow plants to migrate? Do you start to plant species in areas where they weren’t growing before?”

Traditionally there is resistance to the idea of planting outside a species’ natural habitat and much effort goes into sourcing local material and maintaining genetic integrity. Entwisle believes that we will have to start to change our thinking. Scientists have been investigating the impacts and issues of translocation of species for some time, but ethical questions remain. “If you start to plant out species into new areas, you’re effectively doing gardening, and it becomes very species focused,” says Entwisle. “So if you think the Wollemi Pine is the most important thing and you plant it where it needs to be to grow, you’re saying who cares if the local orchids die because the Wollemi Pine needs to survive. You are making some God-like decisions!”

Entwisle sees it as a philosophical dilemma, but he believes that a pragmatic mix of approaches can help. The original Wollemi Pine grove was recently saved from fires in a complex, secret mission. While the grove could be protected – this time – the survival of the species should and does rely on more than this. A ‘back-up’ grove was planted elsewhere in the Blue Mountains but climate change may make its local distribution unviable. There are specimens in many other botanic gardens too and regional botanic gardens are part of emerging strategic projects for preservation of regional flora. The Botanic Gardens of Australia and New Zealand (BGANZ) is a network of city and regional botanic gardens. Victoria has a strong network that is probably unique. Around forty botanic gardens were established during the Gold Rush in the late 19th century. While some function more as municipal parks today, they are keen to become “more botanic” suggests Entwisle. With 34 percent of the state’s flora of conservation significance, it makes sense for regional gardens to conserve, propagate and display their regional flora. A new program called Care for the Rare is helping regional gardens. As part of BGANZ, the Royal Botanic Gardens are propagating plant material and developing labels so that other gardens can display and promote their local flora.

Dr Meg Hirst, who runs the Raising Rarity project, with Neville Walsh and DrAndre Messina at the Seedbank.

Tim Entwisle (far right) at the Dandenong Botanic Gardens to launch a program for regional gardens: Care for the Rare

Botanic gardens hold expert knowledge of living plant resources needed to address the challenges of climate change.

While regional botanic gardens are undertaking local conservation through cultivation, it is interesting to consider that there are many more Wollemi Pines now in private gardens around the world, thanks to a partnership between the nursery industry and botanic gardens. As Entwisle recalls, “I was director of Sydney Botanic Gardens when the Wollemi Pine was first going out for sale and it was really exciting to have this rock star plant!”

Having an iconic plant to talk about helps people connect to plants and spread the stories of plants and their environments. The Raising Rarity project led by Meg Hirst and funded by the Australian Flora Foundation and Melbourne Friends, focuses on assessing the horticultural potential of rare species with a view to their introduction to home gardens. As Entwisle points out, though, the only problem with that approach is that it is sometimes the ugliest plants that are the rarest.

Growing resources to tackle growing problems

Around 80 percent of funding for the Royal Botanic Gardens comes from the state government, the rest is raised by the gardens from activities including walks and other events, cafe and shop sales, and research grants. The gardens also have a strong philanthropic foundation and generous individual donors that provide funds for particular projects, such as collections for the seedbank or work on the state botanical collection.

Another resource is the legion of volunteers. Entwisle is particularly keen to build relationships with volunteers, citizen scientists and other groups including Indigenous communities. There are strong ‘friends’ groups at both Melbourne and Cranbourne. They contribute across a wide range of areas from mounting herbarium specimens – sewing them onto sheets of paper to preserve and put them into the collection – right through to horticultural work, guided tours, and working on conservation projects including seed collection and propagation. “They’re very knowledgeable people,” Entwisle adds. “I’d love to increase our volunteer numbers not only to get more done but also because of that lovely connection through to the broader community.”

Technology can help with engagement, while helping the gardens too. Visitors can take climate change walks, with ClimateWatch, which is part of Earthwatch. Using a phone app they can monitor and record flowering times, for example. “We encourage people to come through the gardens and look at when different things are flowering, such as the Jacarandas or the Banksias,” says Entwisle. It provides citizen science data. With Fungimap people send in photographs and map where mushrooms and other fungi grow. “We could never do that, our scientists could never get to all those areas,” says Entwisle. “We know this works for birds and frogs and it’s the same for us, providing a great way to get information about plants – even discovering new species!”

The gardens’ relationship with Indigenous communities is something that has grown in importance for Entwisle. “Our Aboriginal Heritage Walk is our most popular tour,” says Entwisle, noting how significant it is that locals and visitors alike get to appreciate something about Indigenous culture in the city as part of a living urban history. With plants you can talk about food, medicines, artifacts and ceremony. You can experience a culture more intimately with plants you can engage with directly. Other walks and talks cover bush food, Indigenous plant knowledge, seasonal experiences such as Luc (eel season) and the dry season, a range of activities for children and more. Indigenous children at a kindergarten in Cranbourne use the gardens there to learn about their own culture.

Prior to it being a botanic garden, the Melbourne site was an important meeting place and some very old trees remain from that time. The Long Island area of the gardens has been replanted with indigenous species and the new masterplan to be launched soon proposes a river gate onto the Yarra River. The river is an important part of Melbourne’s Indigenous culture and the gate is intended to increase the connection to it, the wider landscape and to Indigenous stories. “It’s called the Royal Botanic Gardens, so there is that Imperial English sense of the garden’s history in its name,” reflects Entwisle. “So it’s very important that we acknowledge what was here before and what is still here of Aboriginal culture.”

Entwisle sees a change in the ways people are relating to plants, something similar to what happened in Melbourne in the 1970s and ’80s. “I think maybe with climate change and drying landscapes we are noticing and developing an appreciation of our local flora.” It’s not that Entwisle believes people should become specialists, but that Australian species – and local indigenous species – could just become part of the mix of home garden plants, wherever you are. “The more you look at plants and grow plants, the more you see and seek out different and interesting ones and move past the obvious showy blooms.” And that makes our environments and us, all the richer.