Root problem: Climate change is putting food security at risk

Foreground speaks with Ros Gleadow, a scientist dedicated to understanding how climate change affects plants and the lives that depend on them.

This article is part of Foreground’s 2 Degrees themed series of essays

Foreground: What motivated you to study how plants respond to changing environments?

Ros Gleadow: I’m interested in plants and how plants function. But rather than just understanding processes for the sake of them, what I’ve always been most interested in is the relationship between organisms and their environment.

Foreground: You have some very specific areas of research, looking at how some crops respond to increased CO2, how sea level rise might affect cassava and taro, how CO2 and climate change are threatening global food security. How did you come to these particular areas of research?

Ros Gleadow: I went back to do my PhD as an adult. I’d been working in the field and had a masters. I went to see a potential supervisor and he said – this was 25 years ago – plants do interesting things with their nitrogen when you grow them at high CO2 because they become more efficient. There’s a group of plants that make strange compounds that make them resistant to pests, because they release cyanide. And he said it would be interesting to see if growing plants at high CO2 affects these toxic compounds that plants make. So I started working in eucalypts – in sugar gums, Eucalyptus cladocalyx – and that’s what I did my PhD on.

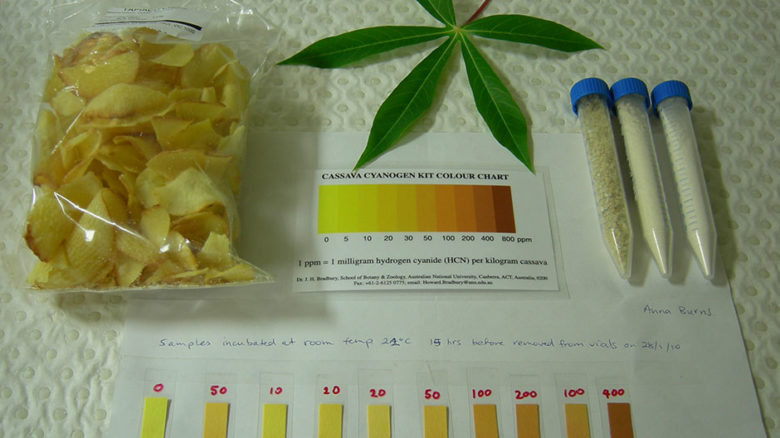

We found extremely interesting relationships between photosynthesis and defence, but as I was reading about that, I realised that two major crops in the world – cassava and sorghum – have very high concentrations of these compounds. The leaves of sorghum can be toxic to cattle and the tubers of cassava can be poisonous to people. So when I left my old lab at the University of Melbourne and moved to Monash to establish my own group, it made sense that I would shift my focus away from eucalyptus – which is what they continue to research – and focus on these crop plants. It was addressing a very important issue: what would happen with plant nutrition in a future world climate?

Ros Gleadow's research focuses on the question: what would happen to plant nutrition in a future-world climate?

Cassava, a woody shrub native to South America, is a staple food for over half a billion people.

When the sea level rises, Ros Gleadow has shown that Taro (pictured) will tolerate a certain increase in the amount of salt in groundwater.

Foreground: Was this problem framed back then in terms of climate change?

Ros Gleadow: We had no doubt at all about it. We’ve known forever that rising CO2 affects plants directly! Well, it’s certainly something I’ve been reading about for 40 years. It’s not new science. But what is new is learning what’s been happening at the physiological level.

Foreground: In looking at the eucalypts were you also looking at effects on animals that consume them, that rely on them for food?

Ros Gleadow: Yes, we did some insect feeding experiments with leaf beetles. We didn’t look at koalas, because the eucalypts we were looking at – there’s only about 30, or five percent, that make cyanide – koalas don’t eat because they’re sensible! But we did find with some of the other toxic compounds in other plants we looked at, that possibly by 2050 there would not be enough protein in the leaves of eucalypts to support a large animal like a koala. There are more digestion inhibitors like tannins too that make it harder to absorb protein, and that’s a direct CO2 effect, nothing to do with drought. This means that trees will have trouble supporting arboreal herbivores by 2050. Period. It’s big stuff. It was back in the news in 1995. And no one was really interested.

Foreground: Is that CO2 effect spread around the world evenly or are there pockets of concentration?

Ros Gleadow: It spreads around the world. But different trees respond differently. When you grow plants at high CO2 they become much more efficient at converting carbon dioxide, water and light into energy – the whole plant becomes more efficient – and the machinery that plants use to undertake that process is essentially protein. It’s a bunch of enzymes and things.

When you grow a plant at high CO2, because it becomes more efficient, you would think, for example, that it might grow twice as big, but they don’t. They grow a bit bigger, depending on what sort of plant it is. The reason they don’t grow as big is that they just downsize that photosynthetic apparatus. They have less protein. They conserve the machinery if you like. When a koala is eating leaves, or a cow is eating grass, or we’re eating spinach, the protein we’re getting from it is primarily photosynthetic machinery. If that downsize is a direct result of more carbon dioxide, it means there’s less protein. So a koala has to eat more leaves to get its protein, a cow has to eat more grass to get its protein, and if we’re vegetarian we have to eat more plants to get our protein.

Foreground: Is this problem compounded by a lack of nutrients and water?

Ros Gleadow: If plants don’t have enough nutrients, the problem is compounded. If you give them lots of nutrients, you have less of this effect of reduced protein. Of course there are other complications. But it turns out that the benefit plateaus. So you can only compensate with a certain amount of fertiliser. If you don’t give plants enough water the increases in efficiency are a positive. The plants are smaller as a result of not having much water, and you don’t see such big decreases in protein concentrations. But of course the plants are small.

If you grow wheat or barley in high carbon dioxide, the leaves have less protein and as the grain grows, it gets protein from the leaves and so the grain itself has less. It’s already been shown that this is happening. And less protein in grains affects baking quality. Work done by Agriculture Victoria in Horsham in Victoria has shown that, again, by 2050 the predictions are you won’t be able to make a proper loaf of bread. It won’t rise because there won’t be enough protein in it. This is a direct effect of increased CO2 concentrations. We’re not getting into any climate models here. People say, so can’t you compensate by plant breeding? It’s a very complex problem and it’s not one that’s easily resolved. Despite the difficulties of reducing emissions, reducing emissions is, in fact, much easier in the end than trying to deal with the consequences.

Foreground: Did you encounter skepticism or any hostility in this early work?

Ros Gleadow: In the nineties, you had individuals who were deniers but the opposition wasn’t organised. Of course there were skeptical people. No-one could deny that CO2 was actually rising in the atmosphere, so if you are looking at direct effects, as I was, you don’t have to get to any climate models.

Before I did my PhD, when the kids were young, I was writing educational programs for teaching biology at university. We were using rising CO2 effects in the atmosphere as a model for understanding how plants and animals function. I found this great report in the library which I realised later was the first IPCC report from 1990. I also came across the first CSIRO submission for that report done in the late eighties predicting the effects on temperature and rainfall for Australia. And essentially nothing has changed since then. All that has happened is that the error bars have got much smaller. We’ve just become more certain. So this stuff has been known for a long time. It’s not new.

The other thing we looked at was some modelling from the Victorian department of – whatever they were then – conservation and environment. They’d done some modelling in 1990 –1991 on distribution of animals in Victoria with changing temperature and rainfall. The modelling shows how with one degree warming the animals would still be able to occur in existing national parks. With two degrees warming the animals – I can’t remember which particular animal we focused on in the end, but a number of different mammals – would be outside existing national parks but still have suitable climate in the state, although not within national parks. With three degrees change there would no longer be anywhere suitable for them in the state.

It wasn’t perfect modelling and you would do it differently now, but the principles are exactly the same: we need to plan for national parks that incorporate a range of different climates so that animals have a place to move and plants have suitable places to regenerate. The reason I say this is that this stuff was going on when the mood changed in the late nineties, early 2000s, when somehow the opposition got more organised. Until then it was widely accepted that the climate was changing and CO2 was rising. I guess Australia didn’t sign Kyoto and they were following the US. Before that the US had signed Rio. George Bush senior has signed that. And climate change has never been politicised in the same way in the UK because Margaret Thatcher was a scientist. She understood science.

In terms of opposition, yes, I have had opposition. I’ve had abuse. I’ve had personal attacks. Anybody working in climate change pretty much has had those things. It’s awful. It’s horrible. For about six months – I had found something that was unexpected, some unexpected responses to carbon dioxide – I would come in in the morning and there would be emails and emails. People trying to smear me. Spread disinformation. Undermine me scientifically. Personal attacks. I know people who had death threats. I didn’t but I certainly had some really horrible, nasty stuff. And so when I’ve had friends who have toyed with the idea of being denialists because they’d talked to someone, I’d say: you know, just have a look at what these people do. Some of them are naive but some of them are not nice people. Pretty much everyone in the field has a story here.

The naturally-occurring cyanide content in cassava increases under drought conditions.

“If you grow wheat or barley in high carbon dioxide, the leaves have less protein and as the grain grows, it gets protein from the leaves and so the grain itself has less.“ - Ros Gleadow

Rising sea and CO2 levels will change what crops are grown in Australia and where. Ultimately Pinot Noir will not be able to be grown in Victoria

Foreground: Aside from CO2 rise, you’ve also looked at responses of plants to sea level rise as a consequence of global warming.

Ros Gleadow: Yes. I tend to do a lot of this work with honours students because I don’t have much money for research. With cassava, for example, it’s very salt sensitive. Taro will tolerate a certain amount of salt in groundwater. We grew cassava and taro experimentally in greenhouses by supplying varying amounts of salt, and I think what we would say is – as farmers know – you don’t grow cassava on the coast, you grow taro on the coast. But as sea levels rise you can continue to grow taro with reduced yield but you won’t be able to grow cassava. Any Fijian farmer will tell you that they know that already. We’ve just worked out why.

Foreground: Food security globally is a huge issue because of climate change. How does it tie in with Australia’s food security?

Ros Gleadow: In Australia we export a large amount of the food we produce. With all the droughts last year, I did hear that we imported grain one month, which is unusual. We’re a major food exporter so I don’t think Australia’s in any danger of food insecurity. But we do have to consider the amount of money that comes in from exports, because if we end up having to use all the food we grow to feed our people, then that’s a big export income that we don’t have. I’m not an economist, I don’t know the answer to that potential problem, but it’s something to consider. The other thing is that there are massive changes going on in agriculture throughout Australia. Some crops are now uneconomic. We’re now growing cotton in Victoria because it’s warm enough and it’s a better use of water in terms of it being a high-value crop. Richard Eckard talked about some of these changes at Government House last week. Pinot noir will ultimately not be able to be grown in Victoria, the taste of shiraz will change as temperatures change. But I think Australia’s food security is quite safe. I don’t think there’s an issue there – we just have to support our farmers economically so they don’t go out of business.

In terms of food security, there are three main aspects: the first is the production of food, and a lot of that is controlled by climate and agricultural practice. Then there’s the distribution of food: are people able to buy it and access it? So you can have food insecurity in wealthy countries. You can have food insecurity with people who are overweight or obese even in developing countries because they can’t access nutritional food. This relates to the third aspect: the nutritional value of plants. So the two things that are of particular interest to me are the relative amounts of protein and anti-nutritional factors in plants.

For example, cassava – which is a staple for over half-a-billion people in the world and eaten by a billion people every day – naturally contains cyanide, which is harmful in itself, but when there’s a drought becomes much more toxic. And yet that plant is very vigorous and will grow well in drought conditions, so if there is an increased reliance on cassava we need to make sure that people process it well. We need to raise awareness of this as an issue because it’s an incredibly hardy crop, a productive, brilliant crop, but the spread of its use throughout the world is faster than the spread of the knowledge you need to process it before consuming.

Foreground: There’s one more question and I wonder what relationship it has to the bigger, complex picture of food security. How might plant invasiveness affect productivity?

Ros Gleadow: There are a couple of points here. One is about humans introducing species to places where they don’t belong. It’s very clear that Pittosporum undulatum has been introduced to Melbourne because the native distribution and the introduced distribution didn’t coalesce until the 1980s. But the other point is that with climate change you do have shifts in populations. Plants and animals need to move to and grow in locations they are adapted to. In the last IPCC report they actually predicted how fast plants can move. Basically trees can migrate at about one to two kilometres a year. And plants do migrate as a result of changing climate. So you have to have reserves for them to migrate to.

But another big thing is that we have huge programs of planting, such as work by Greening Australia, Greenfleet, DELWP and many other organisations, for carbon farming or revegetation or other purposes, and they need to be planting for a future climate. There’s a lot of modelling going on to make predictions about where plants and animals will be in the future. You can look at provenance or choose appropriate species, but we need to be anticipating that change. Trees live for hundreds of years. By 2100 the climate is going to be different. Basically, plant now what is thriving 100 kilometres further north!

The University of Western Sydney is doing a lot of great work on this sort of modelling. Belinda Medlyn is a mathematician, a fantastic scientist doing amazing work which has just been recognized in her receiving an ARC Laureate Award which is the highest honor an individual can get from the Australian Research Council. There’s a lot of great research going on in Victoria, by DELWP and AgVic, for example, and we’re making a big effort to adapt to climate change by reconsidering our planting regimes, investing in research to identify trees that will grow in different areas and deal with heat. There’s a lot of good stuff happening. The bigger picture is that this is a wicked problem and it really is hard to address at the global scale. I think we need to separate that. We should be worried, but we don’t need to despair. People need to know there is good stuff happening and that we can do things to tackle this. And we need to support people who are doing this work.

This article is part of Foreground’s 2 Degrees themed series of essays

–

Professor Ros Gleadow is Head of the Plant Ecophysiology Research Group at Monash University, President of the Global Plant Council, a founder of The International Safe Cassava Working Group and board member of Eucalypt Australia.

Her research group studies impacts of climate change on the chemical composition of tropical crops and wild relatives, as well as the response of taro to sea level rise and the use of cycads by first people.