Our post-pandemic landscapes must be more equitable by design

The disproportionate effects of the COVID-19 pandemic and the climate crisis on the poor and marginalised have helped to ignite protests exposing long-standing inequalities. Much of this injustice is manifest in the way we design and regulate our cities.

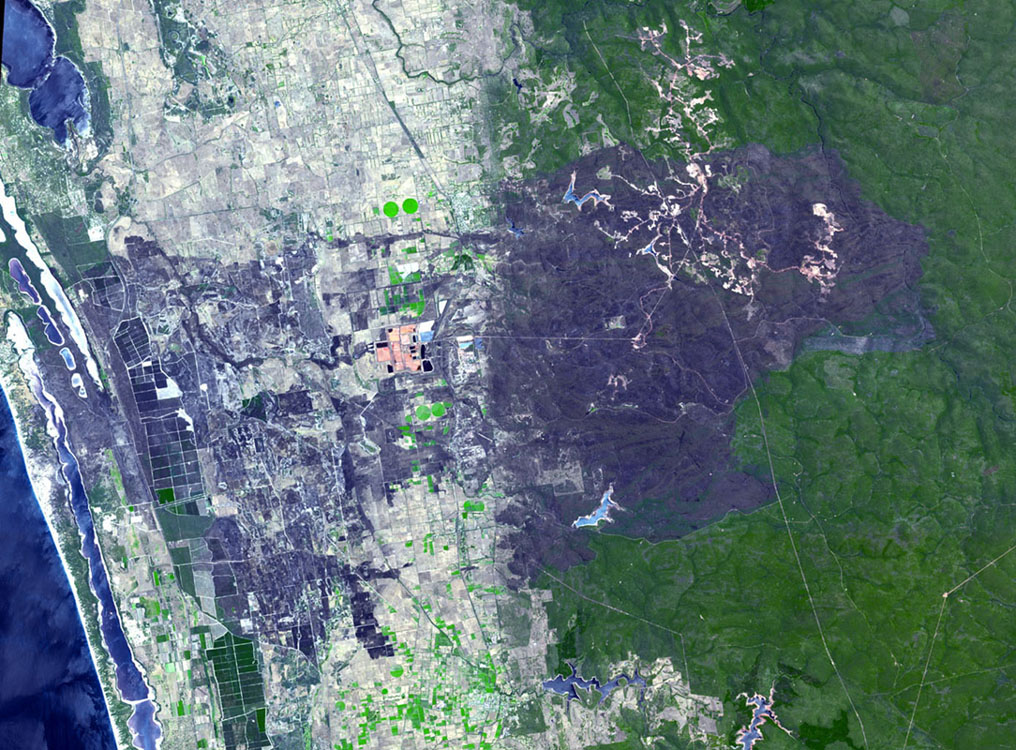

Post-drought, post-bushfire and looking forward to post-COVID, many struggling communities are focused on quick wins for devastated economies. Luckily there are many shovel-ready, easy-to-implement plans that can generate jobs while improving long-term amenity and environments. But there is also a need for projects to deliver fundamental social, environmental and economic change. These changes amount to rethinking an ethics of landscape for our times and for the future city.

Damaging the landscape damages us

The green infrastructure provided by natural landscape systems offers many and varied services, and threats to these systems are now thought responsible for outbreaks of new disease. The latest pandemic is giving us both urgent cause and an unprecedented opportunity to develop new perspectives on urban relationships with natural systems. As others have outlined – and as those working with public landscapes have long known – the built environment now inescapably encompasses the natural environment. So now we can see this better, how can we do better at shaping both?

Some have argued we should address the dire social and economic needs exacerbated by the pandemic and put climate change and other long-term environmental concerns on hold. In Australia the coalition is looking to cut ‘green tape’ “as part of the economic recovery from the coronavirus crisis” and a minister has claimed that “cashed-up activists” should not be able to hold up developments (while cashed-up corporations are permitted to fast-track them). Canada is trashing pollution protections, where “by some strange contagious logic, regulators kill public safeguards and blame the virus.”

Yet others see that COVID-19 must not mask the urgency of the climate change fight, especially since the two are linked. COVID-19 responses may well be a model for climate action as well as action for a more equitable society. Mass behaviour change, policies guided by science and acting for an inclusive greater good are what the challenges of the climate crisis, social justice and the pandemic all call for.

These are also principles that landscape architecture and urban design have always juggled to maintain within funding environments that demand measurable utility value. Built environment designers have become adept at quantifying the usefulness of trees, for example, in lowering temperatures and power bills while prolonging healthy human life-span and increasing property values. These numbers, however, are measures of other values that we also know are invaluable.

Let’s not return to normal

In mid-April, Citylab invited readers to draw maps of their worlds in the time of coronavirus. The ongoing project has shared many beautiful and varied images of altered perspectives from around the world. A common theme has been the discovery and rediscovery of local natural environments. Annita Parish of Montreal, Canada, offers a typical revelation: “I have never had the chance to explore my neighbourhood as I now do. It’s amazing, since it offers me an opportunity to look around attentively, particularly at the trees.”

Many commentators are urging consideration of the opportunities that new perspectives are giving us. Shared widely on social media, We Will Not Go Back to Normal is a mural painted anonymously with words by Sonya Renee Taylor. ‘Ten Lessons The Coronavirus Has Taught Us About The Planet‘ predicted that “a radically new approach to governing and prioritizing our natural environment will be needed emerging from the novel coronavirus pandemic.” Published by business journal Forbes, the 10 points are all about environmental appreciation, protection and enhancement.

The coronavirus crisis is highlighting the strengths of cities, as well as their vulnerabilities, and many in the built environment disciplines recognise they have a responsibility to drive change. This might begin with a consideration of how COVID-19 will affect urban planning and an open examination of planning and development priorities, both short- and long-term.

COVID-19 has created a desire for change requiring local stakeholders to think and act in ways we could not have previously imagined. Landscape architects have long been involved in nurturing strong relationships with communities. Some, such as John Mongard, invest their expertise in new forms of community activism while others, like WAX Design, are speculatively exploring new civic forms. McGregor Coxall’s BioCity Research continues its commitment to understanding urban resilience through scientific and institutional research collaborations.

The future is already here but it is unevenly distributed, and lockdowns have reinforced those inequalities. The rush to parks and cycleways during shutdown has revealed Sydney’s great divide, even while tackling inequality in cities is essential for fighting COVID-19. The innocent pleasure of sunbathing in a park is now a deep moral question that is also highlighting racism in the ways restrictions are policed. In the rush to make our cities safer, “we may be contracting a more dangerous virus – hygienic fascism.”

New Green Deals

Naturally, there is much talk of how communities should be supported as we emerge from restrictions. The World Economic Forum has declared that COVID-19 and nature are linked and so should be the recovery. C40 Mayors are coordinating efforts to support a low-carbon, sustainable path out of lockdown, aiming to shape green recovery from the coronavirus crisis. Although New Zealand’s mid-May budget announced a $1 billion spend on the environment, including jobs for planting and restoration, Greenpeace and others were unhappy that it paled in comparison to an as yet unallocated $20b infrastructure fund.

In their first article in a new series, The Guardian overviews a powerful global movement for economic recovery, where “investors and green groups alike say this is a once-only opportunity to move towards zero emissions”. Entitled ‘Seizing the moment: how Australia can build a green economy from the Covid-19 wreckage’ the article’s argument has been echoed by the Climate Council’s call for resilient recovery and the Greens discussion of what a Green New Deal for Australia might look like. Greenpeace has just launched their #buildbackbetter campaign “to create an economy that is resilient and equitable, one that helps us thrive while protecting our natural environment”.

Back in March, environmentalists globally declared that COVID-19 economic rescue plans must be green. Even before COVID-19 struck, momentum had been building for a “fundamentally fairer and more sustainable” system that would set the global economy on a path to decarbonisation. The United Nations is now calling for coronavirus aid to be directed at firms with green credentials rather than saving polluting industries. In Australia, the Reserve Bank called for a post-pandemic renewables push while corporate giants abandoned coal as renewables supplied more than 50 percent of the national grid over Easter.

Despite all this, the federal government has now directed emissions funding to coal and gas as the fossil fuel industry applauds the Coalition’s plans to support carbon capture and storage. An expert panel review headed by a former gas industry executive and business council president produced the ‘Technology investment roadmap discussion paper: a framework to accelerate low emissions technologies’, which critics say is misleadingly subtitled. A review of stimulus packages has identified further aspects of the inequitable targeting of assistance. These reinforce the neglect of synergies between environmental and inclusive social health that is increasingly seen as essential to not just the recovery, but the reinvention of our cities.

Equity in new public spaces

Equitable access to local public space has been especially important to vulnerable populations during the pandemic restrictions. The value of streetscapes designed for more than just cars has also never been clearer.

Many urban landscape projects aspire to create multifunctional public space, but this ambition is complicated by tensions around rights and responsibilities for access, use and maintenance. At the end of April, Vilnius, the capital city of Lithuania, opened public space to bars and cafes to allow physical distancing during lockdown and help the hospitality industry. This early example has inspired not just imitators and advocates for streets as sites for pandemic response and recovery, but also more ambitious plans for post-pandemic change.

But the rush to convert public space to other uses, both private and public, has met with criticism. A transportation planner has warned that pedestrian-friendly street redesigns that happen without diverse public input can end up harming the communities they serve. In short, ‘safe streets’ are not safe for black lives and pop-up improvements risk deepening mistrust and disenfranchisement. There are those for whom ‘outside’ is experienced from a position of disadvantage, including poverty, ill-health or other vulnerabilities, and that must be addressed before the streets are made more useful for others.

The same gentrification-lite has contributed to increasing and concentrating the poverty of poor neighbourhoods in the United States, according to a recent report: “The zip code you’re born in determines your health, but the zip code you’re born in is determined by your race and ethnicity.” For some, COVID-19 is a life-or-death crisis and where you live determines if you survive. For others, it presents a vision of urban utopia that has seen observers declare that coronavirus is not fuel for urbanist fantasies. At the very least, the assumption that more parks and more people using them equally benefits all “must be tempered by the day-to-day realities of those who don’t have the cheat codes of whiteness to help them avoid racial harassment,” when some users feel threatened. In recent weeks, many have begun an overdue self-education in privilege, realising that what might have been thought of as exceptional circumstances to be responsibly alert to, are part of systemic failures that require revolutionary change.

In May 2020, the first draft of the Rome Charter was released by a transnational group of more than 20 cities and 50 contributors. Aiming to promote the right to participate in cultural life as a condition for a better society, cities “must support every inhabitant to develop their human potential and contribute to the communities of which all are part”.

We may not be all in this together, but we could be, if we rise to the moment.

Dr Jo Russell-Clarke is a registered landscape architect and Fellow of the AILA. She is Foreground’s editor-at-large and a senior lecturer at the University of Adelaide.