Object and spirituality: Building on Country

Contemporary building practices in Australia typically impose international styles. But as author Alison Page explains, there is now a growing movement to understand and apply the principles that Australia’s First Peoples developed over millennia to shape and care for Country.

Bennelong Point, the site of Australia’s most recognisable building, the Sydney Opera House, was known by the traditional owners of the land as Tu-bow-gule, meaning ‘where the knowledge waters meet’. What was the knowledge held here at the confluence of the saltwater and freshwater where the Tank Stream meets the ocean?

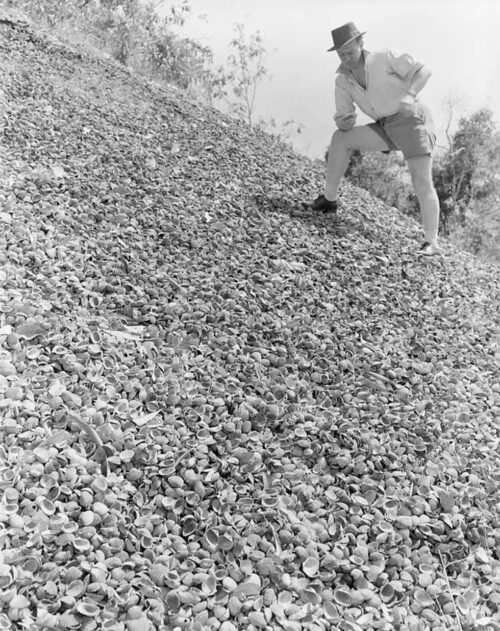

The site was home to extensive middens, said to be up to 12 metres high, which is testament to the abundance and variety of seafood in the area. After the arrival of the First Fleet in 1788, this place was taken over for cattle and renamed Cattle Point. Then, as construction started on the buildings on Macquarie Street, the middens were repurposed into a lime slurry to form the buildings’ foundations and the place was again renamed, this time as Limeburners’ Point.

The knowledge about how to crush the shells and release the lime to bind stone and bricks for building was something that my people practised. I would regularly camp on the south coast with my extended family over weeks in the summer, and one year all it did was rain, day after day, reducing our camp site to mud and water. My aunties collected shells in buckets and crushed the shells, adding spit and water until they made a rudimentary concrete that they laid underneath our tents so we could stay on longer that year.

The value of this shell resource was not lost on the colonists, who used it to build the very foundations of the colony. They were building modern Australia from countless stories, camp fires and meals shared over 65,000 years. This is building on country as a usurper, not a collaborator. The colonists came and appropriated a site and its contents for their own purposes: to re-create the buildings, farms and landscapes of their British homeland on an ancient site that had nourished the Cadigal people physically and spiritually for millennia. The purpose of the new buildings was to honour the memories of other places far away, with a different climate and different plant and animal species. The places were renamed, which meant that the knowledge and meanings encrypted in the First Nations’ language of places was overlaid, often with simplistic descriptions of a site’s function, as in Cattle Point; such a practice completely changed and confused the identity of the locations. Even the renaming of Tubow-gule to Bennelong Point in the early 1790s, after the senior Eora man who became an interlocutor between the natives and British, has done little to show the true meaning of the place ‘where the knowledge waters meet’.

For many years, building practices in Australia have overlaid international styles on this land, but there is now a growing movement to understand the stories and original names. In Australia, the term ‘Country’ has recently been capitalised in many written sources, in an attempt to carve out a different way of engaging with place. There is genuine interest in diving deep into the rich and complex culture of Indigenous people, especially their ecological relationship to the land.

In the Indigenous worldview, Country means a way of seeing the world. Everything is living. There is no separation between people and nature. It is multidimensional and extends beyond ‘the ground’. There is sea, land and sky Country. As anthropologist Deborah Bird Rose wrote, ‘People talk about country in the same way that they would talk about a person: they speak to country, sing to country, visit country, worry about country, feel sorry for country, and long for country.’ Country has Dreaming, origins and a future. The term attempts to encapsulate a sophisticated spiritual connection that Indigenous people have with the land that extends beyond ecology and includes songs, stories and kinship relationships.

So what does it mean to build ‘on Country’?

We realise now how the British colonists blanketed Indigenous lands with their values, placed layers of concrete, steel and glass over the earth with little understanding of its need for care, and believed in the dominance of humans over nature in their approach to architecture and planning. It can be seen in the grid layouts of townships all across Australia, the streetscapes and human-made parks, with buildings turning their backs to the rivers, and roads filling in streams. Streetscapes were favoured over landscapes. Cities like Sydney are lacquered with so many impermeable layers of Western thinking that architects, designers and builders must decide how each new layer can dig below the surface and reveal the original story of Country. How can we, as designers, pick the scabs and allow the country to breathe again?

Just as trees, mountains and rivers contain stories, the design of new places, objects and systems can be a purposeful extension of Country and imbue meaning and story into them, so that as we engage with them over time, multiple narratives are strengthened. If the stories are rooted in cultural values that reinforce our relationship to nature and compel us to care for it, then this will ultimately become our collective and cultural identity.

What a transformational perspective for Australian designers and architects: to be part of an Australian design ethos that views the construction of the built environment as an extension of our creation stories, that these ‘things’ are to be sung into existence with a purpose of clarity that reinforces our connection to Country and our ecological responsibility to care for it.

The framework of Indigenous culture is not just a collection of songs, stories and myths from the ‘noble savage’. What we know now, through our genuine engagement and deep listening, is that beyond the dots in the paintings and the etymology of the languages is a network of symbols that reveal traditional knowledges – knowledges that have allowed Indigenous people to survive successfully despite major changes in climate, with a culture that is responsive to and coherent with nature.

And the potential goes further. The arrangement of knowledges within the environment – built and grown – has been achieved through Songlines as a method of recording vast amounts of ecological data without the written word. In the first book in the First Knowledges series, Songlines: The Power and Promise, co-author Lynne Kelly describes how Indigenous Australians used the three-dimensional world around them – mountains, rocks, rivers, stars – as visual triggers to remember traditional knowledge. This was further reinforced through songs, elaborate Dreaming stories and dance, so that as people moved repeatedly through Country over time, that knowledge was embedded into the synapses of their brains.

Perhaps here is the vital clue to the true meaning behind Tu-bow-gule. Maybe it was a clearing house for knowledge about marine ecology that connected to Songlines within and beyond the Sydney area, so when the nawi (traditional bark canoes) pulled up on the shores of what is now called Circular Quay, people gathered, shared and updated this knowledge around the camp fire.

When Jørn Utzon conceptualised the Sydney Opera House as looking like shells growing out of the ocean and as a gathering place for song and dance, you could imagine that he was connecting with the memory of Tu-bow-gule. Within his practice, he often looked to nature for guidance and cited shells, birds’ wings and clouds as inspiration for his building designs. Although his homage seems purely aesthetic, Utzon was a pioneer of sustainable architecture in that he used prefabricated modular forms; his reverence for nature was not skin deep. I am sure he would have loved the chance to sit with traditional owners at Tu-bow-gule and share a meal or even spend the night and discuss how his building could be activated through ceremony and song. Imagine if the decision-makers and architects had joined them under the stars – perhaps the process of building the Opera House would have been a lot smoother.

Country-focused design is an attempt to reinvigorate ancient conversations about the human connection to nature and how the built environment can play a vital part in this dialogue. It is as much a process as it is a product, in that it goes beyond stylised homage to plants and animals. From the first marks on the page to the decisions by governments, to the materials used in the fabric of the buildings and the public domain, every step has respect for Country at its core.

It is not too late to tap into the traditional knowledge waters at Tu-bow-gule, to define a new Australian design identity – one that truly responds to the ebb and flow of Country and is powered by some very old ideas.

First Knowledges Design: Building on Country by Alison Page and Paul Memmott (Edited by Margo Neale) published by Thames & Hudson. $21.99