Protest and assembly in the augmented city

Augmented reality can serve as a platform for experimentation, protest, and contestation in the city. In this excerpt from Kerb 25 Sara Dean asks: what are the speculative futures we can envision through the tools at hand and the increasing augmentation of our built world?

[This is an excerpt from Kerb 25: Contested Landscapes + Disruptive Practices. Kerb is an annual cross-disciplinary design journal produced through the department of landscape architecture at RMIT University School of Architecture and Urban Design and this excerpt is reproduced here with its permission. Click here to order your copy]

The city and the overlay

The city is a built environment, constructed of metal, glass, and concrete. It is also built of frequencies, signals, and protocols, directly connecting built objects and occupants and allowing them to respond to each other. Through these technologies, the city is becoming a more machine- readable place, and devices are allowing us to access geospatial and proximate data as we move through our environment. As our cities become more augmented, so do our civic actions – assembly, broadcast, and protest.

As the city becomes data-enabled and responsive, new modes of geo engagement are emerging; augmented reality overlays geofences, real-time reporting, public broadcasting, air rights classifications. Infrastructure, traffic, hobbies, schedules, food, finances, and jobs are responding to augmented urban information. And the question of ‘to what end’ is often being answered by the companies with the most investment in the technology. As the built city is a place of capital fluidity, so too are the augmented technologies of the city; driving apps get us to our destinations in the most efficient routes; Uber calculates surge rates in real-time based on momentary supply and demand; companies target us based on both demography and location.

Like the physical city, though, augmented technologies can be used for other interests than capital generation. The protests, barricades, occupations, sanctuaries, and broadcasts of our cities have their digital counterparts. Data layers are not inert or neutral entities, and in treating them as such, they are more likely to be used as political actors of the systems and power structures that created them. In taking protest to non-physical arenas, we must include data overlays embedded in and on top of the environment with our civic and architectural tools.

Layers and exposure

Augmented reality (AR) is a generalised term describing data overlays on a physical object or place. Watching the traffic change on a road through Google Maps is an augmented reality experience, as is a voucher popping up on your phone when you are close to the relevant business, or collecting Pokémon in an app-based game as you walk through a city. Augmented reality is often viewed as a ‘digital window’ through a phone, merging the physical environment with digital information. This can include information about natural environments, commercial and retail spaces, and games, fantasies, and other abstract environments.

Augmented realities often expose aspects of our world that we don’t expect, and sometimes that the technology doesn’t expect. Border Memorial: Frontera de los Muertos, an installation by artist John Craig Freeman in 2012, reveals the locations where people have died crossing the US-Mexico border. This work is a 1:1 memorial in the desert, viewable through Layar or Google Earth: a visceral experience of a data layer and an emergency not otherwise visible on the landscape.

As people roamed cities worldwide, clustering on street corners, parks, and landmarks to play Pokémon GO on their phones, the augmented city was brought into focus (even if the augmentation, in this case, was a city full of cartoon creatures) – and with it an implicit social agreement was exposed. As Pokémon GO players wandered around in search of collectible critters, they would gather in memorials and cemeteries, religious sites, and other sacred spaces. The game was programmed to use public spaces and landmarks for locations, without differentiating based on the type of public landmark. Public outcry over gaming in these places resulted in the gamemakers eventually creating a global dataset of sacred spaces to be eliminated from the game’s collection zones: a set of areas AR had exposed to view.

Area denial/data denial

The use of social media and digital community platforms as means for community organisation – from organising coordinated public events, to consolidating political movements, to documenting evidence of brutality – has been well documented. The effectiveness of the Women’s Marches on January 21st, 2017, in the end comprising 637 simultaneous events, stands as evidence of the efficacy of these tools to create coordinated, independent global events with the same associated branding, message, and memes.

But another way to calculate the value of a technology is to look at the attempts to control and limit access to it. The protest at Standing Rock in North Dakota has become a legislative touch point of the ways to limit digital access, confuse augmented space, and control digital experiences of protest by attacking devices and access points. Protesters experienced chronic lost data, deleted posts, lack of signal, drained batteries, and overheating phones. The Electronic Frontier Foundation’s investigation of these accounts points to the potential use of CSSs (cell-site simulators), which act as a cell tower and collect or interfere with cell data of any phone in the area. Regardless of which technologies were used to intercept the protesters data, the symptoms are evidence of the importance of digital broadcasting and documentation as civic tools.

Digital occupation

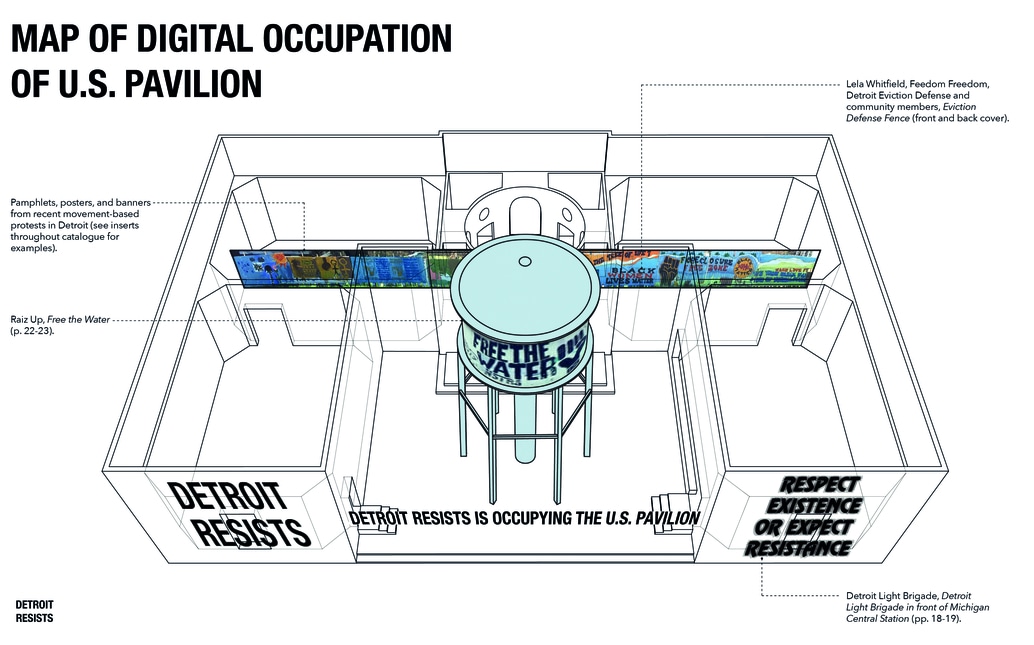

The call for the 2016 US Pavilion in the Venice Biennale, The Architectural Imagination, asked for “new speculative architectural projects” for Detroit, emphasising the “value of the architectural imagination in shaping forms and spaces into exciting future possibilities”. Large-scale interventions were emphasised by the iconic sites chosen by the curators throughout the city. The Detroit community, though, especially the activist community, felt under attack by the call and the curation of the projects for the US Pavilion. This threat was in particular a response to the similarity between the call and local events – the city was in the process of large scale land consolidation by developers, helped by new city policies redefining blight and eviction. By taking on the characteristics of the developer community, The Architectural Imagination, intentionally or not, was embodying this city threat.

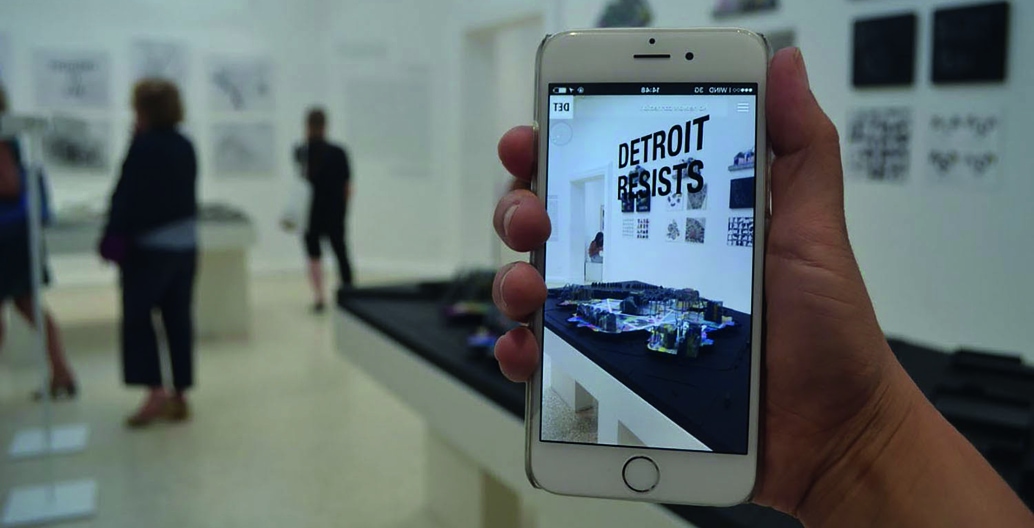

Detroit Resists, a collection of Detroit- area activists and architects, formed to give local voice to the opposition of this project. I worked with Detroit Resists to find a technological means to be ‘present’ at the Biennale and add their voice to the conversation about Detroit’s future. Augmented reality allowed Detroit Resists to create a digital installation on the US Pavilion’s geo-coordinates. This ‘digital occupation’ used new technologies to build on the physical traditions of sit-ins and physical protests, adding activist installations from Detroit directly into the Pavilion without impeding the physical exhibit. The Biennale was flyered, physically and via social media, with information about how to see the Digital Occupation of the US Pavilion. Media picked up the story, with photos of the exhibition layered with digital objects from the Occupation; a graffitied water tower, or an anti-eviction mural on a home fence. Through a layered spatial experience, the community was able to be on-the-ground at the Biennale.

The digital civic body

The history of speculative and ‘paper’ architecture is a history of the ways that we can envision new relationships between people and their environment, or new power systems or value sets of future civilisations. Technologies are similarly offering new visions of future worlds, with responsive data and closer relationships between people and the built environment. But the real test of our agency to impact the future is in our ability to use technology itself as a platform for experimentation, protest, and contestation. What are the speculative futures we can envision through the tools at hand and the increasing augmentation of our built world?

New technologies are often lent to solidify existing power structures – to virtually tour luxury condos for purchase, or convince investors of the potential of a future development. But like all tools, and architecture for that matter, they do not embody a politic through their existence, but through their use. It is our responsibility as architects and designers of cities to see augmentation as a civic device as well as a commercial one. And ask ourselves the futures we are implying through the ways we deploy them in our work.

_

Sara Dean is Assistant Professor at California College of the Arts in San Francisco. Her work considers the implications of emerging digital methodologies on public engagement, urban interface, and ‘smart’ cities.Her research studio VUCA, designs urban strategies to engage complex systems and uncertain futures. This work spans spatial and digital media, with a commitment to open-access data and crowd-production.