Extreme measures: An ecologist’s urban sensors show us just how hot Western Sydney is getting

Dr Sebastian Pfautsch is working with Penrith City Council to quantify temperatures in what is fast becoming one of the world’s hottest cities. His hope? An urgent change in the way we design our cities.

Foreground: You graduated from the University of Freiburg, Germany, in 2007 with a Phd in Forest Ecosystem Science. How does someone interested in forest ecology end up installing heat sensors in the city?

Sebastian Pfautsch: My specialty is understanding trees and their water transport system, and therefore their cooling capacity, in relation to climate change, summer drought and heatwaves. Now I’m using all this fundamental knowledge to apply it to the real world; going out and installing temperature sensors in trees, to compare how different species can help reduce urban heat.

We started with this research looking at tree canopies in early learning centres for kids. We looked at the amount and quality of shade in those outdoor play spaces, which can influence the amount of time you can spend outside. We know that climate change conditions mean that you have hotter summers. That in itself creates a problem when you want to play outdoors, because you have less time available to you; you can only play in the early morning and maybe in the late afternoon, when it’s cooled down again. If you design a play space with no shade or the wrong materials, then you create a place that cannot be used for long. In the morning it heats up very quickly, stores the heat throughout the day and only cools down very slowly in the afternoon and early evening. So you then create a problem on top of climate warming where you have even less time available for the kids to engage in play and exercise.

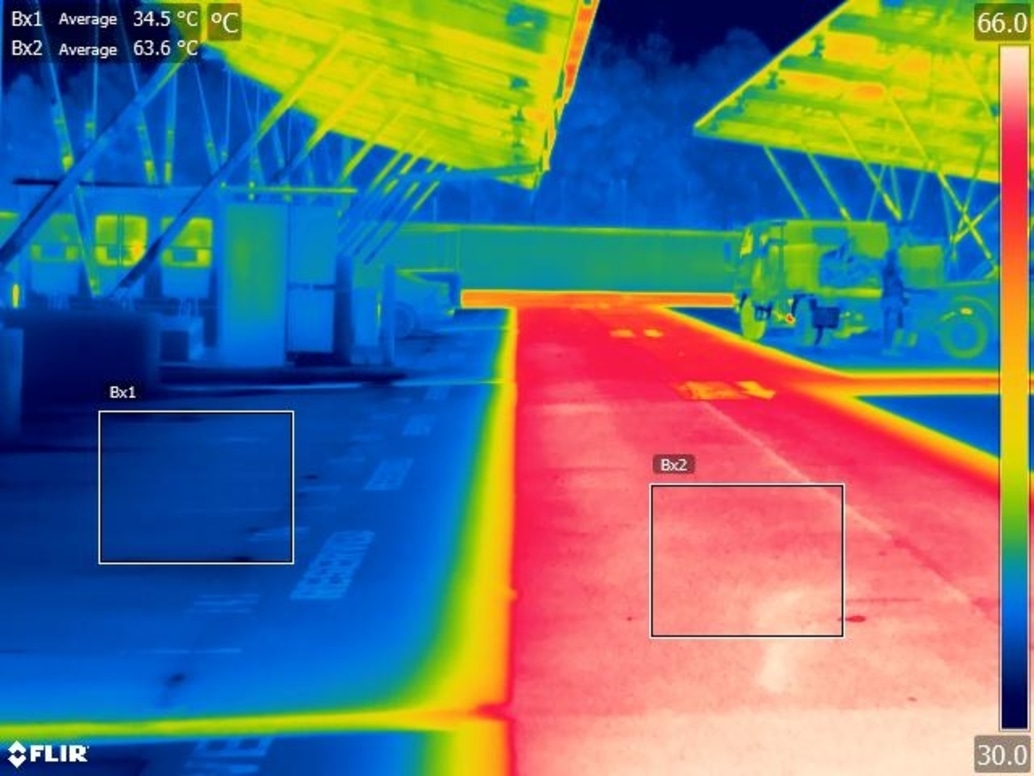

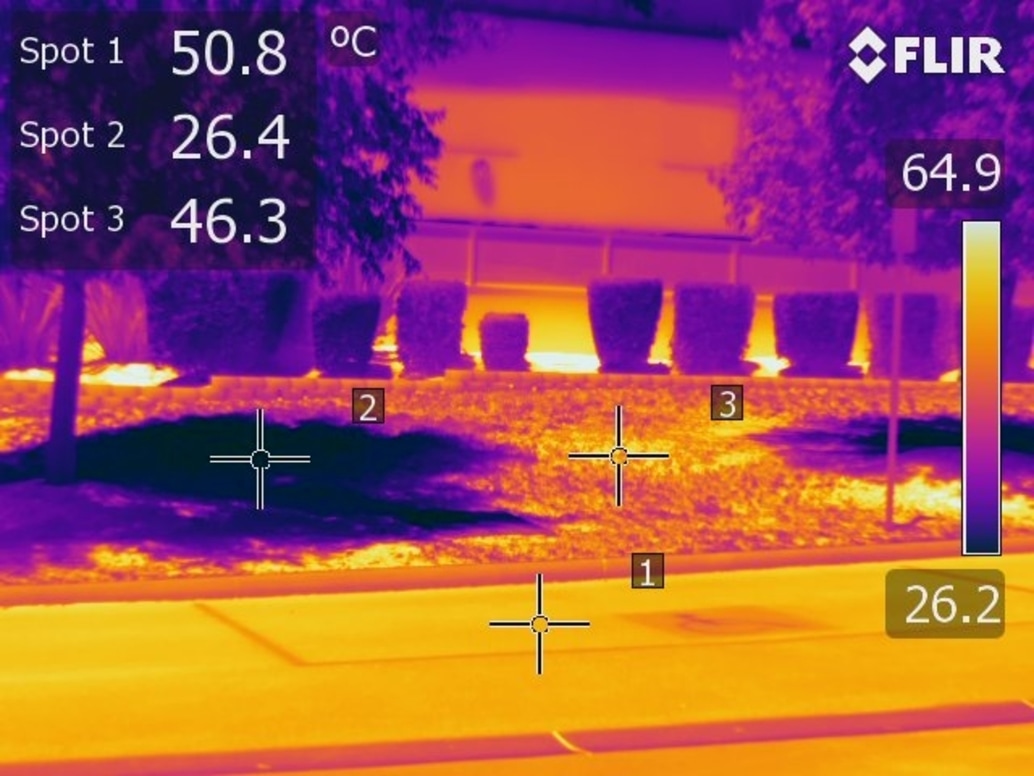

That small project exploded into full-scale research programs called ‘Cool Schools’ and ‘Cool Playgrounds’. I also look at car parks and all sorts of different locations in urban space where trees may not exist, to find strategies to cool these places down. In playgrounds I measure up to 100 degrees Celsius surface temperature. In car parks I see up to 80 degrees surface temperature. And of course, that layer of bitumen in the carparks has a huge thermal mass and only re-radiates the heat very slowly, contributing to the Urban Heat Island Effect, most notably at night.

Foreground: How do trees’ water transport systems help to cool urban spaces?

Sebastian Pfautsch: Evaporative cooling happens during that physical transformation from the liquid state of water to the gaseous state of water. That transformation, which takes place in the leaf, uses energy. This energy is provided by solar radiation. So, when water is transpired from a leaf, the leaf is cooled, and this cooling helps to bring air temperatures down. That is the cooling benefit you get when the tree has water to support transpiration.

Heat becomes an issue in summer, and during this time we also have very little water available. That means trees shut down their transpiration stream to preserve water, so they don’t suffer from what we call hydraulic collapse. The water menisci that span from the roots, where trees take up water from the soil, to the leaves, where they transpire, are like little rubber bands. The hotter the air and the less water in the soil, the harder is the pull. You can stretch the menisci, but if you overstretch, they snap. It’s very difficult for a tree to repair that damage, so for prevention they just shut down transpiration, therefore don’t lose any more water. But for urban space that of course also means that evaporative cooling stops. Shading is then the only benefit that you get.

Now, take the whole greater Sydney basin at the moment. It’s absolutely bone dry out there. That means you have very, very little benefit from evaporative cooling, which has far reaching implications, much more than local shade, as evaporative cooling cools the air and not just the surface. Therefore, evaporative cooling is reaching far beyond your actual tree.

Foreground: Is the solution to urban heat problems simply planting more trees?

Sebastian Pfautsch: No. At the moment, it’s the Premier’s priority to get five million trees into the Greater Sydney Basin by 2030. Well, planting five million trees is very difficult, just to find the space, but keeping them alive to develop a large crown is even more difficult. Then knowing if we run into dry summers, they will just not provide any transpirative cooling benefits. It raises a lot of questions. Just think about what it means to grow these additional trees under the current water restrictions. Every new tree in the ground is super, but tackling urban heat requires more.

We know that green infrastructure is vital when you want to provide a livable climate for a place like Western Sydney. Without trees, summer heat just becomes unbearable. In the new developments out West, you have blocks that are nearly completely covered by houses with black roofs. There’s simply no space to grow a meaningful canopy. This situation means we need to rethink how we plan, build and live.

Foreground: So it’s fair to say you’re less than enthusiastic about the way Western Sydney is currently developing?

Sebastian Pfautsch: Just look into other countries where traditionally you had hot climates. People would never ever put a black roof on their house. It’s just completely opposite from what logic would tell you. I’m doing quite a bit of research using thermal cameras on unmanned aerial vehicles, drones. You can just see these black roof constructions everywhere. It’s a fashion more than any understanding of what’s actually happening to your microclimate when you build like that. The house heats up much quicker, it stores more heat, and because you have no space for trees, there is little natural cooling. You end up with a large electricity bill because you need to run the air conditioning a lot. As everyone is doing exactly that, the additional heat vented from A/C systems does certainly not help to cool your suburb.

There is cool roof technology available. You can have whatever roof material you want and then just paint it in this reflective paint that reduces the absorption of infrared radiation. We’re using this type of technology also on roads and car parks these days. So, this stuff is available, but nobody out west is putting it on.

Foreground: Tell us a little bit about your work with Penrith City Council. What’s driving this project?

Sebastian Pfautsch: Penrith is the hottest place in the greater Sydney area. They only have one weather station available to them, which is out at the Sailing and Regatta Stadium, so it’s close to water plus a lot of open green space. And that’s where the official measurements for temperature for Penrith come from. I know from my previous studies with Parramatta, Cumberland, Campbelltown, that once you move away from those weather stations and you get into urban space, where you have hard surfaces, buildings, traffic, and so on, you have very different temperatures. We saw that you could have discrepancies of up to 22 more days above 40 degrees recorded in urban space compared to a weather station from the Bureau of Meteorology.

I wouldn’t be surprised to find 50-plus degrees somewhere in Penrith this summer, because the weather station has already recorded 48.3, and that’s at the weather station site. We could see 52, 53, 54 degrees in some locations, just because of the way that the urban matrix is configured, where you have very little green space, where you have retained heat that helps to accelerate and accumulate heatwave temperatures. I recorded a heatwave in Campbeltown at the end of last year where you had nine consecutive days above 38 degrees, from the 25th of December to the second of January 2019. And that was last year, which wasn’t an extraordinarily hot summer. But this coming summer might be.

We are excited to get to show some of our research at the Cooling the City Masterclass event. Our research and the event are parts of the larger strategy by Penrith Council to raise awareness around the serious impacts heat has on so many aspects of urban life.

Foreground: What are you hoping to achieve with your Penrith project?

Sebastian Pfautsch: To really wake people up, make them aware of the dangerous levels of heat we are already exposing ourselves to, and then use that information to have a go at how we build in the West. Because once they see the evidence, people will hopefully start to think about what they’re locking themselves into.

The way we develop western Sydney at the moment can’t continue. All of these developments use the same principle of squeezing as many free-standing houses as possible into a limited space. Where space is very expensive, you chop it up into little blocks. You have very little space left for gardens or communal green space. You have lots of space that you plaster with concrete or bitumen. You provide, for example, walkways in each of those new developments, on both sides of the streets. But nobody’s walking there anymore – it’s too hot! So why do we need two sides with walkways? Could we just have one, and then make the other green again?

The data that we collected for Cumberland is already used to inform their master plan and the development control plan. Campbelltown is using the findings from the report that I presented to them for their strategic planning. I would like to see councils starting to advertise ‘cool zones’, urban areas dominated by green infrastructure. I put this in these reports as a recommendation, to increase public awareness of the cooling value of parks and other green space.

Foreground: So how would we go about getting more water into the landscape in these urban environments?

Sebastian Pfautsch: There’s a big push towards water sensitive urban design and opening up surfaces instead of providing more and more impervious surfaces. You can do that for example in carparks and driveways by using compacted sandstone or other porous materials instead of bitumen, which allows water to seep through and become available for plants. In the middle of streets, you can have green spaces and angle the street towards those green spaces, so that when you have water runoff, it actually flows into the areas where you want to grow plants, including trees. Currently runoff flows to the curb and down the drainage system.

Of course, we very quickly run into problems again when it comes to regulations, because road safety, for example, is a big issue when planting trees. There are certain minimum distances that you have to keep. So it’s very difficult to shade a four lane street with big canopy trees. Yet we know that streets are contributing massively to the Urban Heat Island Effect. These are issues that we need to talk about. We need people to have a solid understanding of the current situation, its complexity, and then start to move towards informed decisions that provide real cooling.

We want to settle another 1.8 million people out in Western Sydney. There’s a clear conflict for water. But I keep saying we just need to think smarter about how we keep that water in Western Sydney. Sponge city is a nice graphic word for this way of thinking. On average, we still get seven to eight hundred millimetres of annual rainfall in the Sydney basin. Climate change predictions say that this overall amount will not change.

Now we need to find ways to keep the water where it falls instead of channeling it out of the city. That would mean with 800 millimetres of water available, we can grow as many trees as we want. That’s not a problem. The question is much more about conflict for space. When you want to put 1.8 million people in, where will the space be left for trees? We can already see the pressure from development that is exerted on the Western Sydney Parklands or on the South Creek system.

How we solve this problem is a matter of public demand and also political will, because we know that urban development will make the place hotter. Providing canopy will be vital to just prevent the materials themselves – roofs, walls, walkways, streets and so on – from heating up during the day, and allowing the air to cool at night.

We also need to implement water sensitive urban design and be serious about it, not just dibble dabble around here and there. Have a whole suburb that you develop to incorporate water sensitive urban design from the very beginning. Urban planners and architects are looking to build very large systems underground that can hold stormwater instead of losing it into drainage systems. What keeps us from making it compulsory that every new large carpark needs to use this technology? We have a lot of useful technology available. People need to apply it.

Coming back to trees, it is fact that we still see a net canopy decline across the Greater Sydney Basin, even with all the councils pushing for more green infrastructure. This paradox situation is the result of development and because of mature trees being cut down on private properties. Trees get cut down, left, right and centre because they’re not valued in the way that I think is necessary in a world with a heating climate. Large trees reduce urban heat by cooling and shading. Let’s get serious in valuing that. Retain large trees and help young ones to develop quickly. As summers will only become hotter we will need every square metre of canopy in Sydney.

–

Dr Sebastian Pfautsch will be presenting at Penrith City Councils’ Cooling the City masterclass, 18 February 2020. Click here for more information or to buy tickets.