Blurred Lines: landscapes that bridge the physical and virtual worlds

We now live in a world of overwhelming information and connectivity. But while today’s citizens, and in particular its youth, are saturated in digital environments, our public domain remains a vital site where the physical and virtual worlds collide

With perpetual connectivity fuelling today’s insatiable desire for ever-more information, the ways we socialise and inhabit public space have marked some important changes. Most of us now record more electronic than face-to-face interactions and have at least half a dozen online personas that we present to the world. We can have Facebook selves and Twitter selves, professional webpages and visual catalogues that display our daily experience of the world via Instagram and more. We have generated and now communicate via these transnational visual and written mediums. But are these new ways of interacting enriching our lives or deepening urban alienation?

Those who have traditionally designed our cities have been slow to pick up on the entwining of the virtual and physical in public space. Instead, tech-startups, software developers and UX designers have led the way, connecting our lived experience to the city in new ways. That’s why digital applications have radically transformed our urban experience, taking us to ever-greater heights of digital literacy. The digital world keeps us mobile (Uber and GoCatch), helps us find and make friends (Facebook), find romance (Tinder), be more publicly vocal (Twitter), and be health-conscious 24/7 (Strava).

In a world in which digital citizens are constantly connected via numerous avatars and in which Google pushes suggestions and crowd-sourced answers to an individual’s deepest insecurities, what it means to be either truly alone or truly emotionally connected is arguably more complicated than ever.

Clicking begets more ad revenue for the tech giants, namely Facebook and Google. While we’re not forced into this behaviour, the temptation of yet another dopamine high makes the choice not to click hard to resist.

Ironically, the tech industry is one of the most ardent believers in the importance of face-to-face interaction and experiential depth. They have recently moved to establish workspaces that are both highly liveable and that register traces of the authentic past: traces that cannot be as easily erased by the push of a button or confused through tech jargon.

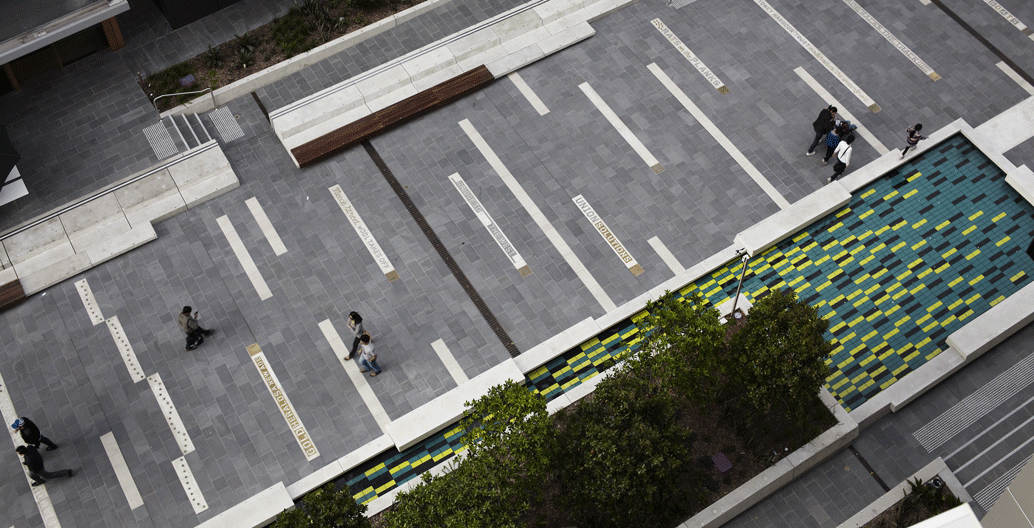

Landscape architects, planners and urban designers have an important role to play in realising these kinds of places, not only to support the innovation districts that the tech industry needs, but also to ensure that our cities remain spaces where we can have unfettered face-to-face interaction.

Spaces of unfettered face-to-face interaction Image: Simon Whitbread.

Spaces of youthful informality Image: Simon Whitbread.

Spaces that promote health and well-being Image: Simon Whitbread.

ASPECT Studio's Goods Line. Image: Florian Groehn.

The rise of the innovation district

Across California’s Silicon Valley, tech giants sit side-by-side in “innovation districts”. Apple, Google and Twitter colonise the outskirts of a city and its arterial roads with shuttle buses to and from these districts – most notably in San Francisco. Evidently, cities understand the inherent value of these districts. Sydney’s proposal to develop the White Bay Power Station into Google’s new Australasian innovation district would have been a good example of this, had Google not pulled the plug due to the area’s poor public transport links.

The Sydney office of landscape architects ASPECT Studios worked with Google on the ill-fated White Bay proposal. The practice has been collaborating with digital infrastructure experts to consider what the future might be for innovation districts in Sydney. For Sacha Coles, director of ASPECT Studios, the answer does not lie in dramatic innovation. In fact, it may simply require a realisation of the existing value that landscape architects are already very good at delivering.

Together, ASPECT Studios and Arup Digital have been exploring what bright young startups need and desire to develop their ideas. While some findings, such as internet connectivity and public transport connections, are obvious, others, such as a high-quality public domain, are more surprising. Real-world spaces and landscapes for face-to-face social interaction were seen as just as important as their digital counterparts in setting the stage for serendipitous encounters and social play.

Arup’s urban renewal advisor Hugh Gardner has been collaborating with Coles in developing various digital strategies and approaches to public space. For them, the sheer volume of time we dedicate to our devices (there are approximately two smart devices for every human on the planet today) means less time for spending in the local park with friends and family – implying that how we design our public spaces may help avert the “digital revolution” from entirely overtaking our daily lives.

New technologies “don’t just enrich our experiences; they ‘become’ our experiences” in the words of author Michael Harris. Or as Marshall McLuhan would have said “the medium is the message”. For the youth of today, physical mobility doesn’t hold as much importance as it once did. Instead, access and connectivity to information are everything. It’s little wonder, then, that there are declining rates of car ownership. In the face of such massive shifts in attitudes and choices, Gardner and Coles argue that public spaces are more important ever before. Projects such as the Good’s Line and the landscape spaces of nearby Darling Quarter, both by ASPECT Studios, seek to provide physical alternatives to online worlds.

ASPECT Studio's Goods Line. Image: Florian Groehn.

ASPECT Studio's Goods Line. Image: Florian Groehn.

ASPECT Studio's Goods Line. Image: Florian Groehn.

ASPECT Studio's Goods Line. Image: Florian Groehn.

ASPECT Studio's Goods Line. Image: Florian Groehn.

Delivering the goods

Sydney’s Goods Line, a project from ASPECT Studios, Chrofi Architects and other collaborators, addresses the innovation agenda through landscape themes of “authenticity” and “wellness”. It is a project which seeks to take many of the catch-phrases of our decade and reclaim them for landscape practitioners. Phrases such as “landscape-as-platform”, “social infrastructure”, “authenticity” and “user experience” are all common within the world of startups today and each is used as a starting point for design explorations in the project.

The Goods Line is built on and among the remnants of industrial history, threading its way past the Disneyland that is Sydney’s Darling Harbour. It is the remains of what used to be a vast network of freight rail lines and in fact the first rail line to open in Australia in 1855. In its original use, it was dedicated to transporting coal, timber, wool, grain and agricultural produce to and from Darling Harbour, where it was shipped around Australia and the world. Its use for freight declined in the 1960s, with the rise of containerisation and road freight. Now, redeveloped warehouses sit alongside the Goods Line: architecture adapted from this largely forgotten world.

ASPECT Studios envisaged this industrial infrastructure transformation as a piece of “social infrastructure” that would connect some of the most important knowledge-based industries and neighbourhoods in Sydney. These institutions are distributed from Pyrmont and Ultimo all the way to Surry Hills and Redfern and include the Australian Technology Park at Eveleigh, educational and media institutions, such as the ABC, UTS, TAFE and the Museum of Applied Arts & Sciences (Powerhouse) – with the latter the subject of many recent headlines over proposals to move part or all of it to Parramatta, following the Liberal NSW government election promise.

The self-devised brief to transform the old Goods Line into social infrastructure, developed with local government agency Property NSW, gave ASPECT Studios (as the design lead), pause to consider what kind of landscape they were actually designing. The resulting space is not a street, nor is it a park, nor is it a forecourt for the adjacent buildings. Somehow it aims to be all of these and more, in a complex hybrid.

The Goods Line aspires to be a new typology, learning important lessons from pop-up parks, contemporary workplace design and event spaces, while also integrating some of the lessons of post-industrial parks that were developed around Sydney in the 2000s. This mix of the playful and the historic makes the landscape very much a multi-functional and eclectic space. To some extent it is its context that provides its multifunctional energy, but it is also the mix of surfaces and spaces that makes this animated space come alive.

This aspiration to be a swiss army knife of sorts poses an interesting question. Just as we have an app for everything today, do we also need a park that does everything? This is a question the park provokes and is one that Sydney must consider, if it is to develop spaces that bridge the digital and physical worlds in this frenetic age.

The Goods Line retains and enhances Sydney’s industrial past through careful overlays of precast concrete that overlap its industrial remains, creating a partial palimpsest – partial because the industrial is not erased but retained, masked and montaged in layers. The industrial elements are complemented by curated “weedscapes” that are among the most beautiful elements of the landscape.

The space is dotted with “wellness” spots, inviting active participation such as table tennis and outdoor exercise, a performance amphitheatre and a grass platform for either relaxing in the sun or kicking a ball. These jostle in close proximity to signs and infrastructure of the digital startup district that characterises the area, such as long outdoor co-working desks and power outlets for laptops and shady study pods that take advantage of the shade of existing fig trees.

The space is fun but there is also a sense here of a collision of virtual and physical worlds. These active spaces along the 500m length of the Goods Line are a continuation of the work ASPECT Studios began with the Darling Quarter: their 4000m2 playground (the largest in central Sydney).

Darling Quarter by ASPECT Studios. Image: John Maramas.

Darling Quarter by ASPECT Studios. Image: Florian Groehn.

Darling Quarter by ASPECT Studios. Image: Florian Groehn.

Darling Quarter by ASPECT Studios. Image: Florian Groehn.

Darling Quarter by ASPECT Studios. Image: Florian Groehn.

Not so disrupted after all

Despite today’s digital disruption, which is at once hype and brutal economic reality, what it means to be directly connected with each other in a digital age hasn’t fundamentally changed. For landscape architects and urban designers, the public domain is a battleground for these connections. This means that landscape architects have the potential to have more impact on the logic and connectivity of our everyday lives than any other design profession.

It is in the public domain where opportunities for genuine interaction are presented and intensified, or conversely, dissipated or prevented. Just as the car – the apotheosis of individual technology – is now being surpassed by the online avatar, landscape architects are well-placed to intervene in these new urban landscapes of digital youth.

Today’s children will have no choice but to be resilient and transform with a rapidly changing socio-economic and employment landscape. Our urban landscapes should support young people on this journey through spaces that stimulate multiple ways of being.

To do this, all of those involved in the design of such spaces will have be conversant, not only with aesthetics and programs that support virtual-physical exchanges, but also with new technologies such as augmented reality, as bridges to and from other worlds.

––

Dr Scott Hawken is an urban designer, landscape architect and landscape archaeologist with local and international experience in professional and academic contexts at the University of New South Wales (UNSW). His work focuses on the agency of open space as a variable in the spatial makeup of the city.