Spanning the gap between park and precinct: Tanderrum Bridge

A new pedestrian bridge in one of Australia’s most heavily-trod sports precincts recalls the civic generosity of a different era.

Before Melbourne was Melbourne, it was home to the Kulin nation. When visitors from other lands came to visit, they would be granted safe passage and temporary use of the land in a ceremony called Tanderrum. Generations later a new bridge bearing that name has been designed and completed at the Melbourne Olympic Park, just in time for the 2017 Australian Open. True to its name, this January the new bridge welcomed and granted safe passage to swarms of visor-clad, sun-oiled and mildly jet-lagged visitors, as they made their way to see Federer’s return.

Granting safe passage is not always so simple, however, when pedestrian herds compete with the logistical support needed to manage over 200 hundred large events a year. Such logistics include everything from accommodating Madonna’s legendary flotilla of roadies and support crew, to the unruly chaos of 10,000 Wiggles kids, to the not inconsiderable safety and security challenges of an Australian Open, this year reaching a record attendance of close to 90,000 spectators, in one day. All of which makes the business of how you get pedestrians in and out of Melbourne Olympic Park very important, particularly when it is moated by busy roads, commuter rail tracks and the Yarra River.

Tanderrum Bridge can serve tens of thousands of pedestrians in a single day. Photo: Pete Glenane/HiVis Pictures

Tanderrum Bridge's material qualities recall an investment in simple public infrastructure from a previous century.

Subtle realignments in Tanderrum Bridge integrate it with the landscape. Photo: Pete Glenane/HiVis Pictures

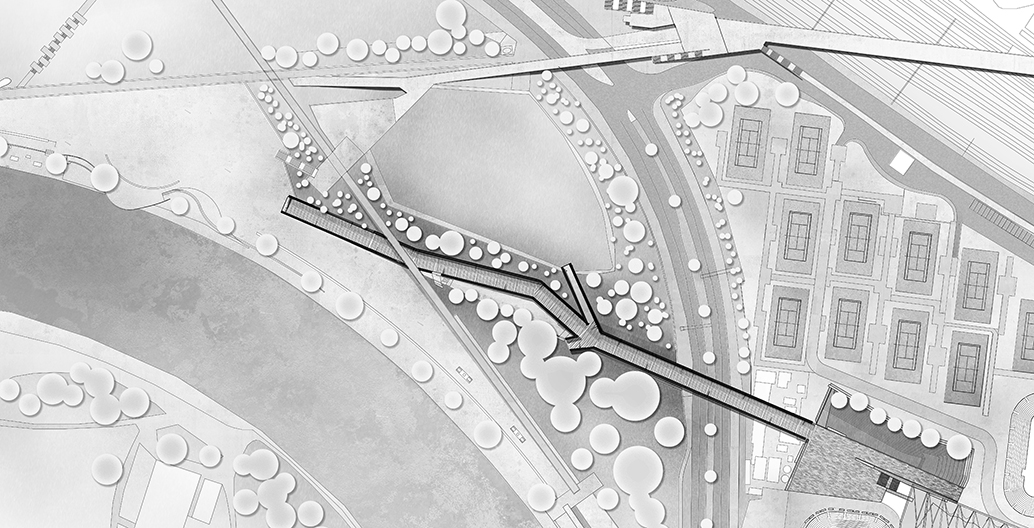

Tanderrum Bridge in plan.

As one of the later elements in the Melbourne Olympic Park Masterplan, Tanderrum Bridge is more than a logistical exercise, however. Its budget may have been modest compared to the Rod Laver Arena four-year facelift, currently under way, but it is arguably more important in civic and symbolic terms, as the bridge supports the delicate balance between prime public space and commercially supercharged event precinct. As a zone of unbridled commercial sponsorship and sold out events that together supports more than 1500 local jobs, the Melbourne Olympic Park is unlike any other urban park, to the extent it swells the city’s coffers.

In a context of intense commercial use and enormous pedestrian flows, Tanderrum Bridge enhances a seamless network of universal access, from pathways and bridges to parks and forecourts, dotted with shade trees, benches and places to gather: all vital components of the public park. It forms a gateway to a contiguous pedestrian terrain, from Flinders Street Station to Richmond, where hunched phone-gazing pedestrians need not sleep-walk across a single traffic intersection.

At this point the Office of the Victorian Government Architect (OVGA) deserves some praise, as this kind of high quality urban design is not, sadly, the default setting for pedestrian infrastructure. When the Melbourne Olympic Park Masterplan was established, the OVGA established a design quality team to provide advice and design advocacy in relation to new buildings and infrastructure within the park. It is partly due to this advice that the park is not otherwise entirely swamped by pop-up shops, Kia display stages and Ginza-priced sushi carts.

The sculptural quality of Tanderrum Bridge means the experience of walking below it is as rich as walking across it.

Tanderrum Bridge's concrete spans are wrapped in a lightweight weave of steel rods.

The bridge has been designed to minimise disruption to the existing landscape below it.

Tanderrum Bridge forms a gateway to a contiguous pedestrian terrain. Photo: Pete Glenane/HiVis Pictures

It also helped that the design of the bridge was procured through a design competition, which resulted in the commissioning of John Wardle Architects, in collaboration with the Boston-based architectural practice NADAAA. Designed to withstand the deadweight of thousands of pedestrians, the bridge’s substantial concrete structure might have looked like any other city elevated by-pass. Here, however, the substantial girth of its concrete spans are wrapped in a lightweight weave of steel rods. This sculptural materiality continues in the bridge’s balustrades, lighting and various gateway elements, recalling an investment in simple public infrastructure from a previous century.

Added to this material craft, in plan the bridge is cranked subtly and realigned, to integrate carefully with the award-winning landscape of Birrarung Marr. Three slight shifts in orientation occur in the bridge’s span, which starts at Birrarung Marr’s lower terrace and rises up slowly to cross Batman Avenue, to arrive at the outer courts of the tennis grounds. These shifts not only minimise disruption to the existing landscape, but also mitigate the long, straight, undifferentiated quality that afflicts nearby William Barak Bridge. Instead, traversing it feels like a journey, with detours and nuanced views, and platforms where you can stop and look out over Yarra River and the historic Speaker’s Corner.

It has become customary to rename new bits of the city after aboriginal leaders. In borrowing the same conventions that resulted in Melbourne being named after the Prime Minister of England at the time of its colonisation, this custom profoundly misrepresents the indigenous relationship to land as one of ownership or dominance, as was witnessed in the background debate to the naming of Perth’s Yagan Square. It is therefore refreshing to see a new piece of high quality public infrastructure that is not only more appropriately named, but also so handsomely honours its name.