Penned in: How public space is failing our children

Young people need opportunities to socialise and find their place in the world. Yet the opposite is happening in our public areas, which seem to be increasingly hostile to their presence.

For many years, the suburbs have been home to families. Their quiet streets and generous blocks provided space for children to grow. Recently, however, suburban housing has seen reduced block sizes, narrower lot frontages and ever-wider double garages. The latter reduces passive surveillance of our streets, while increased road connectivity brings with it more cars, further reducing the opportunity to play and hang out beyond the garden. The previous generations’ fond memories, of time spent playing with mates in the street after school, have been consigned to history.

Meanwhile, at the higher end of the density spectrum, apartment living is transforming from the domain of the single or couples without children to a growing option for families. The increasing unaffordability of detached homes, combined with the expanding market for apartments, has made high density living the only option for those seeking affordable housing close to the city. In 2007, only 3 percent of families lived in apartments; by 2016 this number had doubled to 6 percent and the number of children in Australia growing up in apartments looks set to steadily increase in the years ahead.

This is problematic, as the apartment market has traditionally focussed on the needs of those without children. As more families join this demographic in high density housing, tensions are rising. In 2016, WA Today published an article highlighting this issue, giving an example of a complex where children were banned from playing in communal outdoor spaces. While families now make up a significant percentage of apartment residents, it is increasingly clear that the apartment market itself is not meeting the needs of children.

Knock on effects

There are few public places where adults don’t feel safe, whether walking down the street, meeting friends in the park or eating out. Regardless of their needs or abilities, be they bike riders or the elderly, most adults are made to feel welcome in public spaces. This is not so for children. Despite making up 20% of Australia’s population, if children aren’t with a guardian, their access to public space can be extremely limited. Playgrounds and skate parks largely constitute the only consideration paid to children in public space terms. Important as those spaces are, they alone are not sufficient.

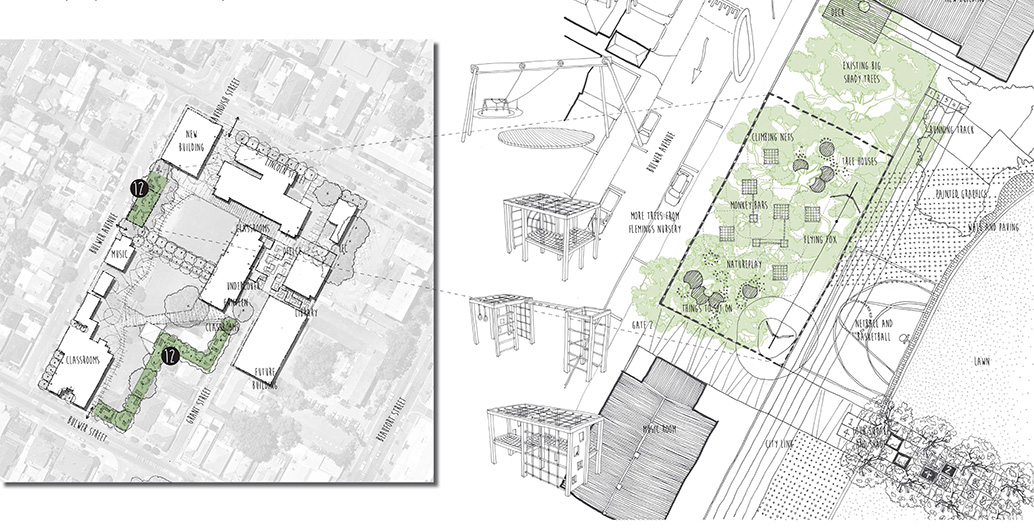

Collaborating on a new playground led to exciting design outcomes Image: UDLA/Highgate Community

Children from Highgate Primary School Master Planning Image: UDLA

Collaborating on a new playground led to exciting design outcomes Image: UDLA/Highgate Community

This lack of space for children to be children carries particular concerns. For children, play is not simply a fun way to pass time, but is also a key developmental activity. Children learn social through play, the ability to meet new people, negotiate rules and acceptable ways of interaction. Play builds confidence in children, teaches them how to take risks and when to moderate behaviour.

Play is also the way children get most of their physical exercise. Playing and being physically active as a child is a precursor to being physically active as an adult. Furthermore, physical activity, play and being outdoors have a positive impact on both physical and mental health. Sadly, in Australia one in three children do not enjoy a healthy level of daily physical activity, which is linked to one in three Australian children being overweight or obese and one in four suffering mental health issues. For those professionals that are responsible for shaping the places in which we live, it is vitally important that they start to look for ways to get children back outdoors, playing and socialising.

Yet our urban and suburban environments are heading in the opposite direction. In cities, the provision of vibrant streetscapes too often translates into coffee strips, bike paths and urban activations dedicated to adult recreation. In suburban areas, a focus on the car has had devastating impacts on children’s capacity to move freely around neighbourhoods. Consider the cul-de-sac – Australian children who live on cul-de-sacs are more likely to achieve their daily levels of physical activity than a child who lives on a through street, yet our urban development policies increasingly support the use of connected/grid streets over cul-de-sacs to improve traffic flow.

If in doubt, ask

There is a disarmingly simple solution to this problem – the key to ensuring that children are considered in the designing and planning of our public spaces is to talk with them. Children are shockingly underrepresented as stakeholders in discussions about our public spaces. According to the United Nations Convention on the Rights of the Child, of which Australia is a signatory, children not only have a right to play, but to have a say about decisions that affect them and for this to be taken seriously. Why do we ignore this fundamental right?

Is it a throwback to the belief that children should be seen and not heard? Many adults I speak with question the ability of children to meaningfully contribute to the discussion of what are considered complex concepts. Surely their experience and understanding of their environment is equally important as ours, as they are living that experience now?

Even when we attempt to meet children’s needs, if we don’t consult with them directly, we can miss the boat. In my role as a play consultant with the not-for-profit organisation Nature Play WA, I recently escorted a group of children to a new popular playground in Perth. After 30 minutes of play we had a little design debrief. They had set themselves the challenge of creating a design for their new playground and we were using these debriefs to assist them with their design process. They talked about the parts of the playground they enjoyed and the parts they didn’t, but not one of them mentioned the art works that were sculpted into almost all of the play elements. They hadn’t even noticed them. Very possibly, a large portion of the playground’s budget was spent on elements that the kids didn’t even notice. This example is symptomatic of our approach to public spaces for children: we consistently design for the adult’s experience, without considering how the intended user is experiencing this space.

Engaging with children is not onerous. As with adults, it is about building up a relationship of mutual trust and, importantly, respect. To be respectful to children, we must be mindful of our role as an adult in children lives. Children are so used to living under direction from adults that they will often provide a response that they think you will want to hear, perhaps rather than what they really think. So it is important to consider how information is shared to ensure genuine interactions.

There are also ethical requirements, to ensure children’s safety. This includes ensuring correct supervision, that responsible adults are supportive and aware of the work, that those working with the children have the right qualifications. As with any consultancy, it is important not simply to tell them what we are doing. This is not engagement. This is informing. We must work together to develop a design that meets the needs of their community.

Lastly, it is important to have fun, to provide opportunity for children to respond in ways that are non-verbal and verbal… and to play!

UDLA was lucky enough to work with Highgate Primary School on the masterplan for their school site, as part of the My Park Rules project. This project was a great example of a community, in this case a school (including parents, teachers and the students), working together with the design team to create a masterplan that met their specific community needs. With UDLA acting as a design facilitator, the children became actively involved in all phases of the design process: providing drawings, ideas and critiques to help change an existing condition into their preferred one. Community involvement in the process was just as important as the outcome, providing parents, students and teachers with a deeper understanding of their place and the children with a sense of ownership. As designer, UDLA was given a better understanding of what was required to fulfil their needs. Probably most importantly, the children were involved in the decision-making process. This process introduces children to the role of an active citizen. It is a valuable step towards ensuring our next generation is both involved with and passionate about the things that affect their lives.

The process of engaging with children reminds us that children experience things differently to how we might remember experiencing them. Just having this awareness is a huge step in the right direction to creating public spaces that encourage children to engage, play and be a part of a healthy community.

Shea Hatch is a registered landscape architect in Western Australia with UDLA. She recently completed a Masters in Public Health (UWA) with her major research paper a qualitative investigation of barriers and motivators for children’s independent outdoor play in Western Australian Policy, with Dr Julie Saunders and Dr Hayley Christian. Shea has also spent time working with the not-for-profit organisation Nature Play WA as a play space consultant.