Garden Cities no more: Australia’s leafy urban centres are under pressure

Australia likes to tout the ‘liveability’ of its capital cities. Yet a recent report has found the country is broadly failing to live up to its much-celebrated reputation for healthy urban living.

Australian governments, at both state and federal level, like to brag about the purported ‘liveability’ of their capital cities. A recent report, however, has found rhetoric and reality are two very different things. The report, published by the Centre for Urban Research at RMIT University, has found that while most metropolitan strategic plans in Australia aspire to achieve walkable, liveable, 30-minute cities, these aspirations aren’t translating into the implementation of effective policy. Furthermore, across measures related to walkability, public transport, and public open space, it found little evidence that governments were achieving even their own stipulated targets around liveability.

The report registers as a wake-up call, particularly when it comes to the burgeoning pressures on parkland within Australia’s supposed ‘garden cities’, as densification and population increases.

“We’re seeing a loss of private open space, which means that we’re losing biodiversity and we’re also losing green space that helps cool the city,” says Professor Billie Giles-Corti, one of the report’s authors. “And if more people are living in an area, there’ll be more pressure on open space. I don’t think people necessarily need the backyard, but we do need enough open space.”

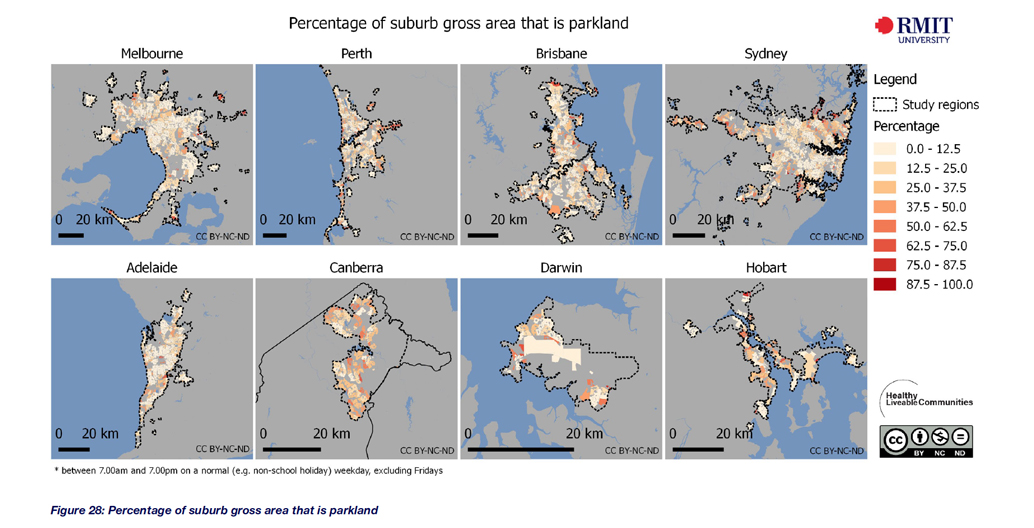

The report found that Melbourne and Adelaide, which both routinely top The Economist’s notorious ‘liveable city’ rankings, actually include comparatively little parkland within their metropolitan boundaries. The report found just 20 percent of Melbourne can be considered public open space, while it found Adelaide is the most park-poor capital in Australia, with a mere 10 percent of the city qualifying as parkland. By way of comparison, 57 percent of Sydney’s metropolitan area is allocated to parkland, with Perth not far behind at 40 percent.

Rymill Park, Adelaide. Image: via City of Adelaide

Western Park, Canberra.

Tarban Creek looking south to Sydney. Image: Sardaka

A lush tree canopy in Centennial Park, Sydney. Image: EcaterinaGo

Ku-ring gai Chase National Park. Image: Brian E Jensen

Across many cities there is immense pressure on parkland, as population growth continues to surge, while private outdoor space shrinks. Many inhabitants are forced out into groaning green spaces that were established generations ago. There is little evidence that contemporary leaders share the foresight of their forebears, in building for generations to come.

Giles-Corti points to the striking lack of planning evident in many of Australia’s biggest urban and suburban developments of recent years. Fisherman’s Bend in Melbourne is a prime example of a new, almost park-less suburb. It managed the unenviable double act of delivering the worst car-centric tendencies of 1950s planning, while failing to allow for any of that era’s civic generosity.

“It’s difficult to build new open spaces once the horse has bolted,” says Giles-Corti. “What we have in Fisherman’s Bend is very wide roads. I would argue that we should be thinking about how we can use those roads in other ways, for open space. People are going to need it.”

Most policy experts would agree with Giles-Corti, with access to parkland a broadly accepted and important characteristic of a liveable city. Parks, of course, have long been appreciated from an urban beautification perspective, but research is also increasingly finding they have very direct and quantifiable benefits to public health. The World Health Organisation has found that urban green spaces, such as parks and playgrounds, can promote widespread improvements to mental and physical health, and reduce rates of death and disease.

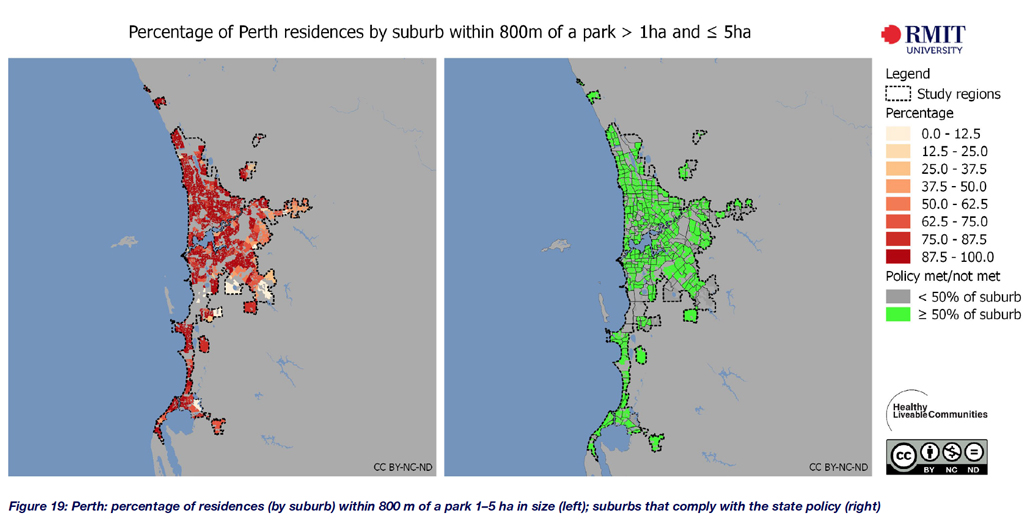

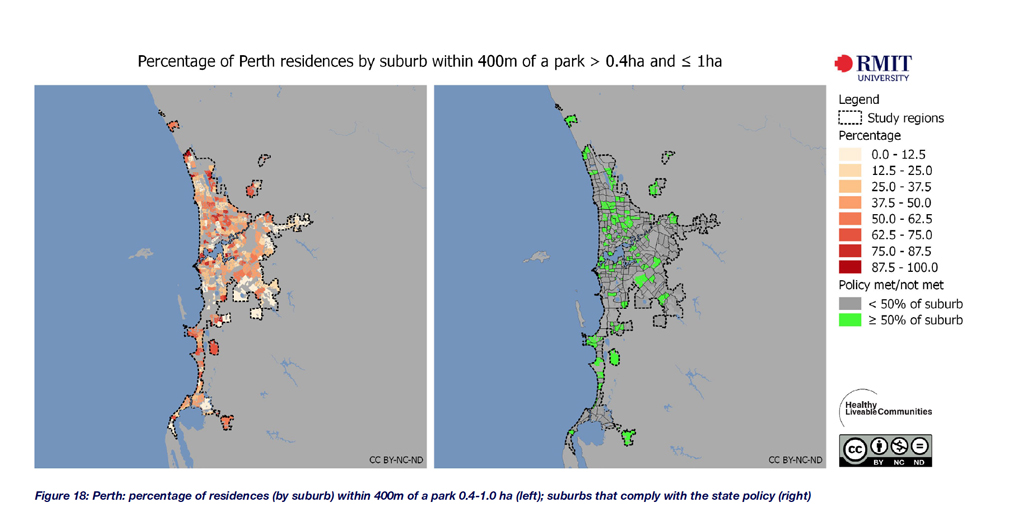

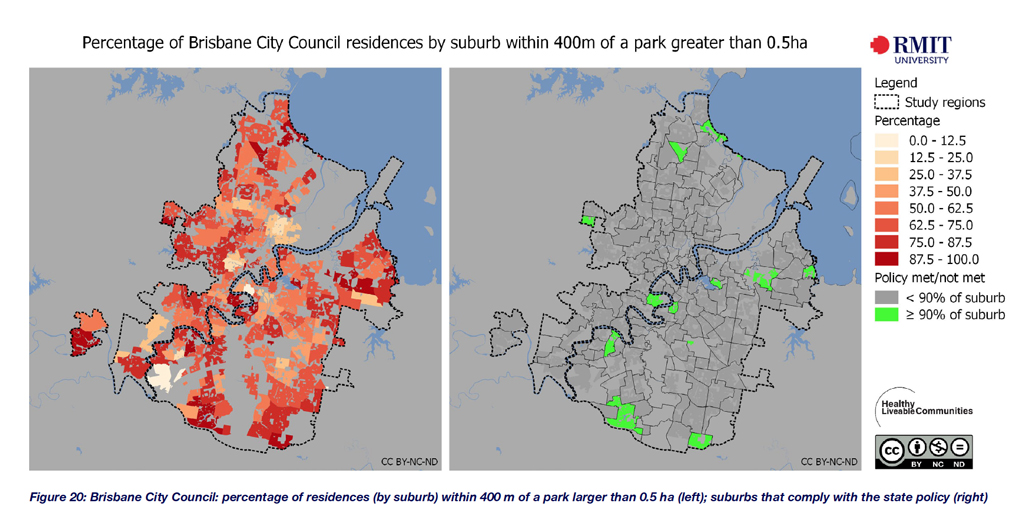

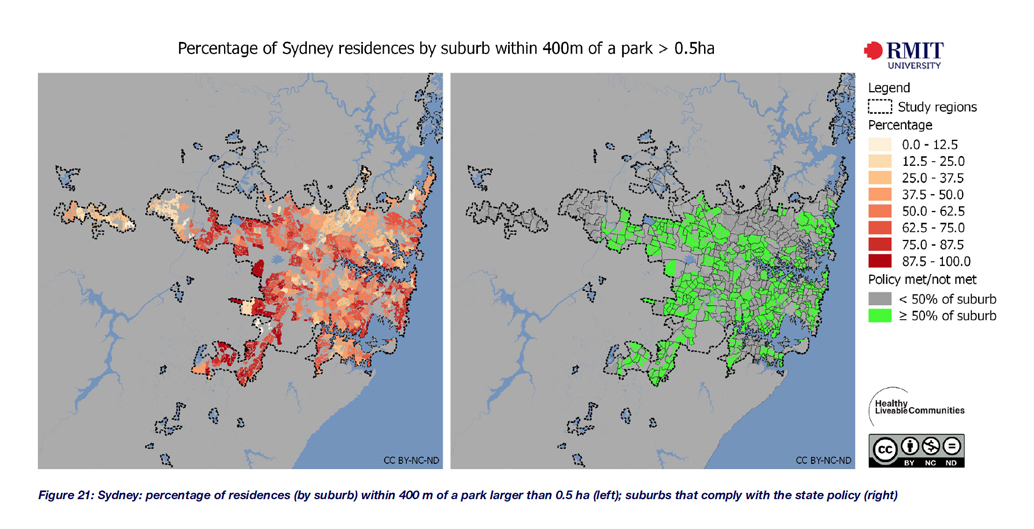

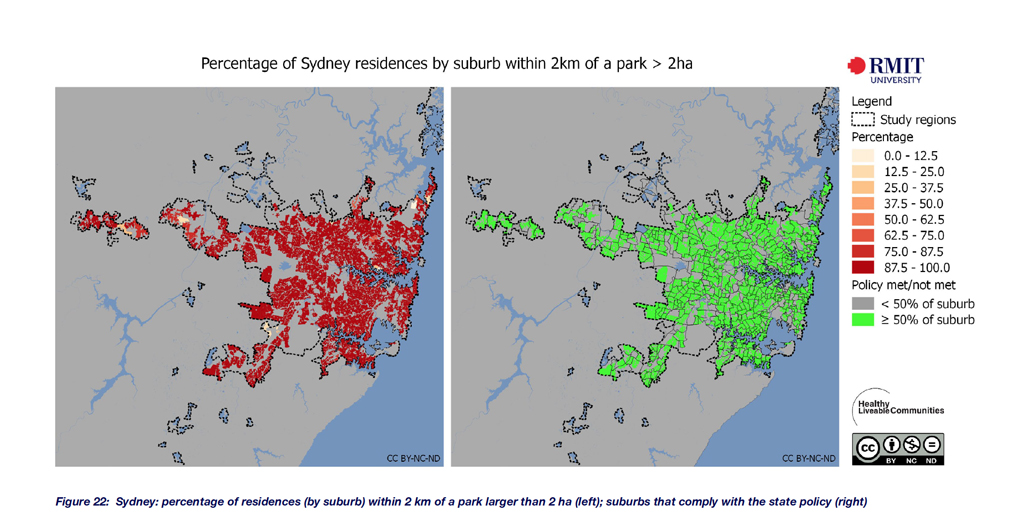

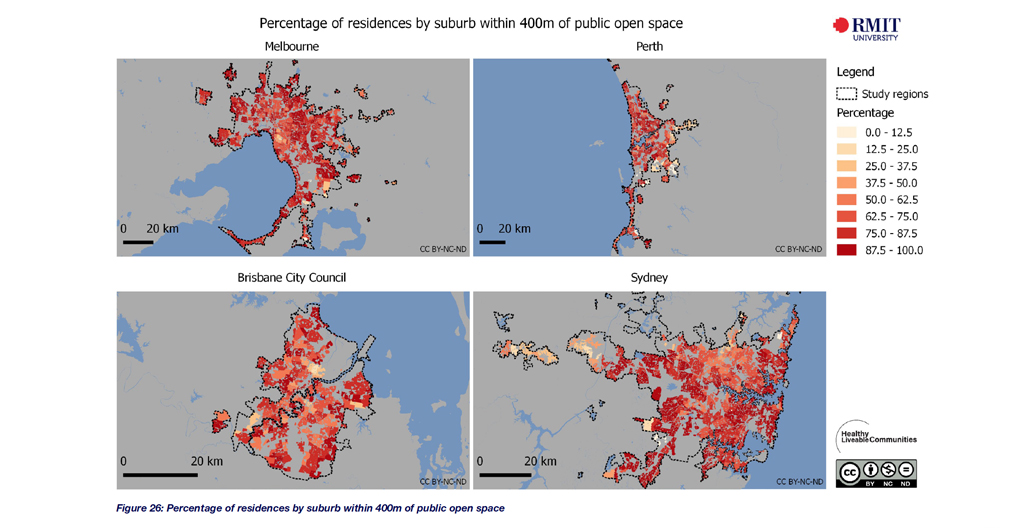

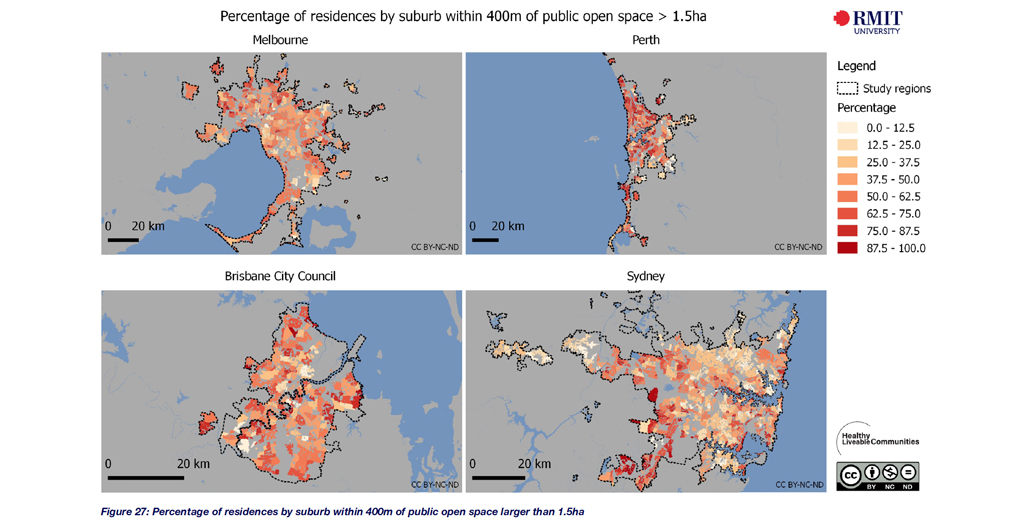

State government policies for Perth, Melbourne, Brisbane and Sydney do recognize the importance of parks, with all four states legislating policy that requires access to public open space within 400 metres of dwellings (or a five-minute walk). Three of the four states also have policies requiring access to large parks within longer walking distances. Almost all these cities, however, have failed to meet their own targets. Sydney is the only city that achieves its modest goal, which requires ‘most’ dwellings to have access to public open space. 59 percent of residences have access to public open space greater than 0.5 hectares within 400 metres. More dwellings in Melbourne (82 percent) have access to a park within 400 metres, than dwellings in other cities (39–58 percent), but Melbourne nevertheless falls short of its ambitious target of 95 percent.

While Melburnians might be able to crow about their comparatively generous access to parks, most of these parks are on the ‘pocket’ end of the scale. This is important, because for parks to meet their full potential from a health perspective, size matters. Evidence from Victoria suggests that pocket parks don’t do much to encourage walking or to improve mental health. For this, you need parks greater than 1.5 hectares in size. Notably, in Perth, the report found that people living within 400 metres of public open space were more likely to walk recreationally than in the other cities surveyed. Why? Probably because the parks in Perth tend to be larger.

Source: RMIT.

Source: RMIT.

Source: RMIT.

Source: RMIT.

Source: RMIT

Source: RMIT.

Source: RMIT.

Source: RMIT.

In summary, for healthier cities, lots of pocket parks might not be the answer. Fewer, larger, higher-quality public open spaces within closer walking distances of dwellings will be more successful in encouraging recreational walking.

As Giles-Corti readily admits, though, unlike in previous eras, most of Australia’s urban centres now face a dire shortage of space, which makes it exponentially harder to provide generous urban parkland. Australia’s cities just can’t build the kind of parks that our forebears might have considered appropriate. So we’re going to need unconventional, contemporary solutions, and clever planning.

“For example, Melbourne Water has a lot of open space that it uses to protect waterways and pipes,” says Giles-Corti. “So, sensibly, its saying we’ve got 30,000 hectares of open space that we can develop into green infrastructure. How can we do that?”

“There are governance issues to deal with of course, but we’re in a situation where we have lots of infrastructure, and we need to use it to create better outcomes for the community. Smart cities will use infrastructure in a smart way.”