Petrol-powered planning: Car parks, COVID-19 and the future of urban retail (part 2)

Award-winning, multi-million dollar urban design nearly falls victim to calls for more road space in Geelong, while the perverse outcomes of ‘free’ parking fail to prevent demands for more of it. When it comes to cars and their parks, political expediency often trumps long term vision.

Free and public may be the benchmark for parking, as we discovered in part one of this feature, yet multi-billion-dollar industries depend on Australians buying and running cars—around a million new cars are purchased in Australia each year, and car purchase is one of the lead indicators used to measure the health of the economy. RACV’s 2019 figures put personal car costs at something over $200 per week— purchase, depreciation, loans, fees, insurance, repairs and petrol. Running two or more cars, as over half of Victorian households do, adds up to around a quarter of a household budget and is similar to or greater than the median weekly rent.

Given the amount of time spent in cars, they function as (in the language of car advertisements) “your home away from home” and “a great place to raise a family” in more ways than one. Car advertisements have long been a source of horrified fascination for me but these have taken a new tone in the COVID-era. One, set to a nostalgically lit stream of images of life moments (weddings, camping trips, parent-child bonding with wind in sun dappled hair), reminds viewers that “we’ve been your Sunday drive, your taxi, your home away from home, shared your journey”. Another offers, with bittersweet reminiscence, “remember how we used to just get in our cars and drive?”—“it’s time to reclaim the road trip”. Another shows people looking longingly out of their houses at their parked cars: “while we’re all parked for a while…we’re still anticipating your needs. We’re here for you”.

Both dire business predictions and apocalyptic films derive their power from empty streets with a deathly lack of traffic—the same conditions used to advertise cars. But all, I suppose, have in common the way the Australian nightmare future of Mad Max (inspired by George Miller’s experiences in road trauma wards in the 1970s), melds car and person.

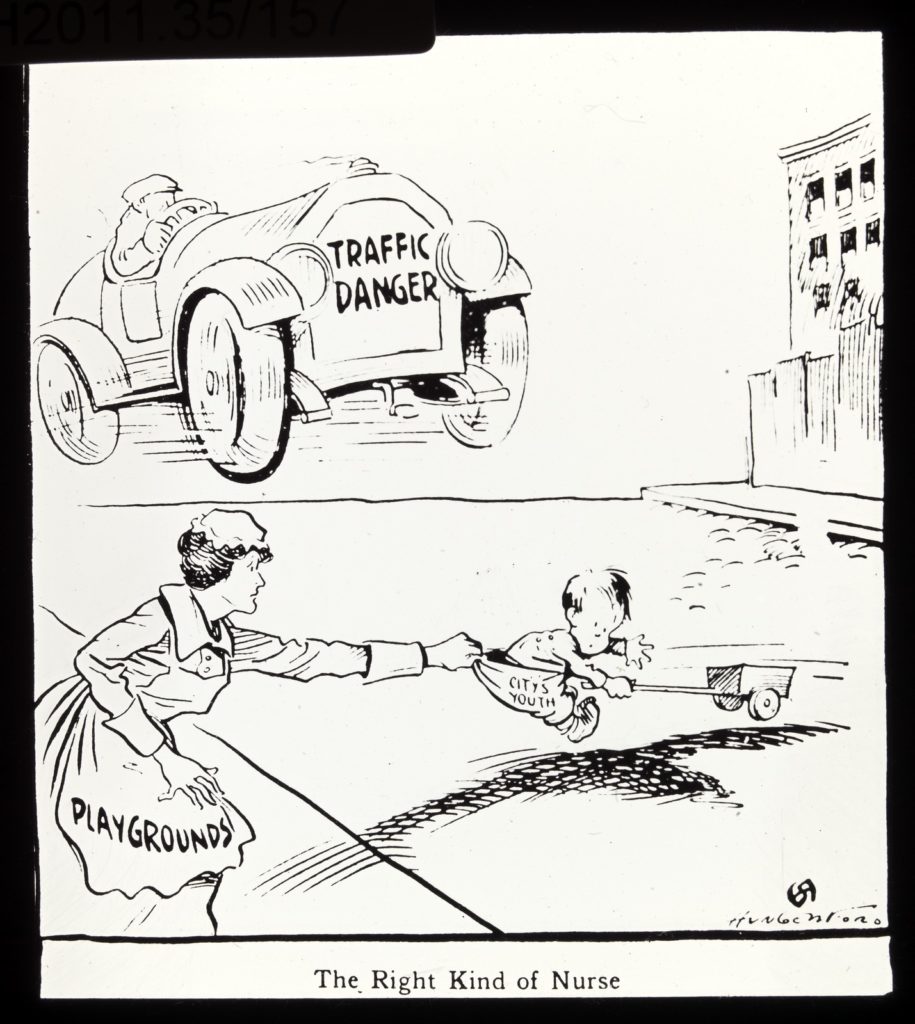

Conflating car with identity, family, and life itself is a core part of the marketing of cars but also of the logic of many urban planning debates. Infrastructure decisions are made on the basis that people need cars to get to work, and that they need to work in order to pay for the car. The poverty, health costs, and unequal burden of car dependency in cities are far more abstract than the idea that people—and particularly the kinds of people Australian politicians like to talk about (ute-driving tradies, night-shift nurses)—should not pay parking fees or fines.

There is something about car storage that the popular narrative demands be free of charge, despite individual spaces costing in the vicinity of AU$60,000 in construction and land costs alone. These direct costs are spread across governments, developers, and real estate costs— as well as in the opportunity costs of space not used for other purposes, and the externality costs of subsidising car use over other transport modes.

“It is a truth universally acknowledged”, to paraphrase Jane Austen, that a car costing its owner several hundred dollars a week is always in want of a free car parking spot. This accepted truth underscores intense political engagement where parking is concerned.

In Yarraville, a small pre-automobile shopping strip in Melbourne’s west, the 2015 installation of parking meters by Maribyrnong city council was so deeply unpopular with local retailers that, after protests, vandalism, and other actions failed to deter the hated AU$1.50 per hour parking fees, chairs were thrown and councillors beaten up at a council meeting.

Unhappily for the local councillors, but happily for me in that I gained an anecdote neatly encapsulating how seriously people take car parking, the next day a trader representative compared the parking meter brawl to the Arab Spring—meaning that at some point, violence is the only political recourse. The Yarraville parking meters were switched off.

A victory for revolutionary politics, perhaps, but the same retailers also once fought away a pop-up parklet taking the place of several parking spaces—suggesting it is not just aversion to pecuniary change, but change itself, that shapes Australian centres and streets. The Yarraville parklet, like many others, proved popular (and perhaps more importantly, profitable) after the fact, and became permanent.

The Magic Parking Pudding

In Norman Lindsey’s children book The Magic Pudding, a grumpy but delicious desert is capable of being endlessly eaten, leading to a host of characters pursuing the pudding for its promise of bottomless fulfilment. Such is, I think, the dream of parking in politics—that everyone can be satisfied.

Alas, especially when it comes to the public curb space, while competing visions for the future often rely on how street space is allocated or reimagined, the space is finite and these demands cannot all be simultaneously met. This is especially true when the demand is for unlimited, unpriced storage on public space for vehicles many times larger than humans themselves. Every politician wants to promise more and free parking. How to achieve this within the contested space of the actual street is a different challenge.

In the COVID-19 climate of Melbourne’s CBD, impossible ideas about the ‘pudding’ of street parking space are being newly propagated. On the one hand, the politically indefensible idea of a doctor being issued a parking fine has been enough to prompt the state government to stop councils enforcing parking rules including time limits. Yet commercial garage car parks in the CBD have been simultaneously closed by state government policy defining garage workers as non-essential. This is despite the fact there are 24,754 on-street spaces in total in the City of Melbourne but nearly 200,000 off-street spaces.

There is far greater capacity to meet parking demand off the street, and even parking operators are campaigning for ways to re-use their languishing spaces. For various reasons, however, access to garage space is less politically important than the imagined dream street parking space ‘out the front’.

Adding to the challenge, in the context of central hospitals in Melbourne, street parking space largely means residential areas—to which residents already lay fierce claims of entitlement. The City of Melbourne and other Melbourne councils issue residential on-street parking permits to residents, based mainly on the age of the dwelling. Thousands of residents of high value terrace housing in the streets surrounding Melbourne hospitals hold these parking permits, which allow residents unlimited parking in areas otherwise subject to time or meter limits (though not guaranteeing or reserving them a car park). At the same time, COVID-19 debates prompted the issuing of thousands of street parking permits for hospital health care workers—overlooking the issue that the spaces are already largely allocated for residential parking permit holders, who then complain to the council about their street being ‘parked out’. The directive preventing councils enforcing parking rules also means that council officers are not allowed to enforce parking meters or time limits—such as those privileging permit holders of either type.

Both the street and the local government have in these ways been set up to fail. There is not enough street parking, and while prevented from managing competing demands for it, they are held accountable by variously aggrieved aspiring car parkers. This pressure flows through to limits on other ideas for curb space—bike lanes, green space, or other uses.

The problem is not unique to Melbourne or to COVID-19—emerging forms of (auto)mobility have also been making difficult claims on public curb space and on the parking policies used to govern curb space. Greg Marsden, Robyn Dowling and others characterise the curb as a difficult to govern ‘boundary’ space onto which new forms of mobility—including car-share, delivery, and ride-share services—are pushing for more codified and marketised claims. This places pressure on legacy governance systems, themselves encoding an earlier, 20th-century automobility transformation.

While automated vehicle technologies are sometimes imagined as technologically and market-driven transport models ‘freeing up’ road space, governance of the curb is far more locally and politically contingent. It is also dated: while the future seems technologically advanced and seamless, the reality is the way we manage streets for car parking is not. Much like toilets, parking underscores how we exist in cities but is largely unspoken of, and the technology involved has not really advanced since the early 20th century.

Ideas and technologies do exist for finding and managing parking space more efficiently, but a political default to ‘predict and provide’ standards tends to stymie innovation. I have often been contacted by app developers looking to digitally connect parkees to parking spaces: but who butt up against the fact most parking (outside of airports or some limited CBD and institutional areas) is free of charge, and that little data exists even on its extent let alone its availability.

In Victoria, the state government is also a source of conservatism around parking. Daniel Andrews has spoken of preventing councils from introducing “bureaucratic delays” to opening up curb car parks to the envisioned post-COVID New York style eateries. One might get the impression local governments are in the habit of preventing change, and that the state government will bravely step in to reimagine curb space. This can sometimes be true (as with Geelong’s “Green Spine” drama, which I discuss later) but in the cases of many inner Melbourne councils, it is local government that has often been pursuing parking change over past decades but struggles to get state government sign off.

In 2019, planning minister Richard Wynne criticised Moreland’s proposed transport strategy and revised parking plan; the state government later officially rejected Moreland’s proposals (to be fair, citing a lack of supporting research). Of the City of Yarra, Wynne’s electorate, the minister found enough critical evidence in an anecdote that some of his constituents had been “driven out” by car parking regulations—“he was a plumber and she was a night emergency nurse…they ended up having to leave the suburb of Richmond because they were getting booked all the time”.

In 2007, St Kilda Road bike lanes were proposed by the City of Melbourne but stopped by Tim Pallas, who also intervened to stop plans for 40-kilometre zones in the CBD. In 2018, in response to the City of Melbourne’s parking policy “transport strategy refresh” proposals, I recall that aspects informed by my own work (a discussion paper on parking, much of it proposing selective re-use of curb space) were dismissed by Andrews as “purely academic” (although in this case, the state government did not actually prevent the city’s changes).

In late 2019, the State Minister for Roads Jaala Pulford prevented even a temporary trial of parking changes to Sydney Road despite council, local community (via a survey) and VicRoads support. Traders have long opposed change to Sydney Road, particularly where parking loss is involved. When the trialled road changes were proposed, Labor MP Lizzie Blandthorn called on Minister Pulford for assurance that no removal of parking on Sydney Road would be attempted, even temporarily, as the continued success of this precinct is dependent on it remaining accessible for all commuters.

But 2020 brings new winds to the City of Moreland and to Sydney Road’s future. Promising outdoor dining in Moreland, the same Labor councillors who fought parking policy changes under the banner of “fair parking Moreland”, have switched to enthusiastically promoting the idea of outdoor dining on closed street parking, ahead of local government elections. The fear and promise of COIVID-19 has unleashed some new imagined possibilities, at least within Labor politics.

“They got their wish”: (Soylent) Green Spine?

Meanwhile, in Warrnambool, south west Victoria, there is some (again, anecdotal) evidence that the saying to “be careful what you wish for” is playing out around car parking.

Earlier this year, The Standard reported Warrnambool was “to get free parking to combat coronavirus…in a bid to help struggling businesses”. City retailer groups finally got what they had long lobbied for: “when the coronavirus pandemic struck, they got their wish—the city council voted to allow free parking as part of its COVID-19 measures to help stimulate businesses struggling during the shutdown.”

An unfortunate truth of parking is that providing more of it, and especially at little price to the driver, often does little in the way of increasing visits. For more visitors, the space needs to turn over, to actually be available, and retailers have a long habit of parking in the spaces in front of their own shops—one fairly reliable way to prevent visitors accessing it. This tendency to park for hours or days is usually what prompted the introduction of hated parking meters and time limits to begin with. Such histories of attempts to ‘free up’ parking are usually forgotten in reprised calls for the return of free parking. In Warrnambool, traders had long lobbied for free parking. But having gotten this wish, the ABC reported in July how “Warrnambool’s free parking trial backfires as motorists ‘overstay their welcome’”. Predictably (to a parking researcher), traders and employees had parked in the spaces: “instead of allowing shoppers to come and go with ease, some traders and their employees reportedly hogged the parks in front of their shops all day, raising the ire of neighbouring traders.”

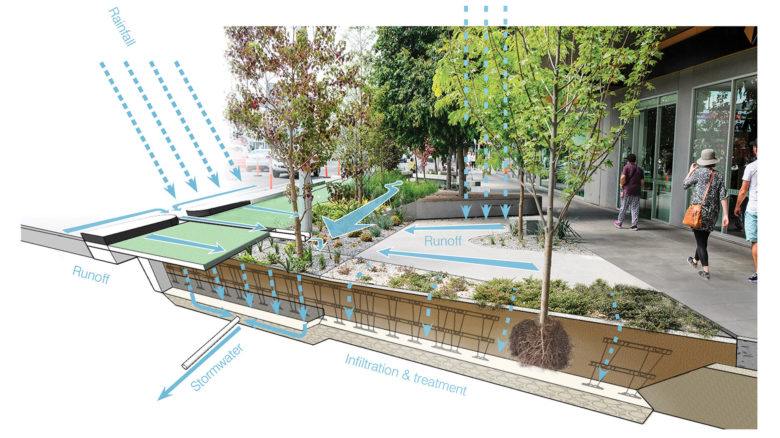

Inbuilt drainage systems as part of Outlines' proposal for Malop Street, Geelong. Image: Outlines

The Malop Street upgrade involved creating a protected bicycle lane as well as outdoor seating. Image: Outlines

Car parking along Malop Street would be inflected to surrounding streets. Image: Outlines

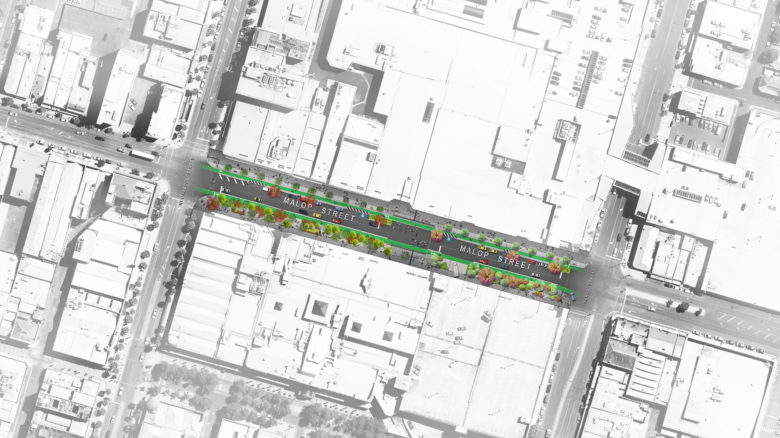

Another recent forum for competing visions of parking and retailing futures has been Geelong, where the Malop Street “Green Spine” project combines separated bike lanes, outdoor dining and garden areas in a 200-metre stretch of road space reallocation. The first phase of the project had been built in 2018 as part of the “Revitalising Central Geelong Action Plan”. The project has not been popular, at least not at council level.

In what was decried by bike groups as “a retrograde move” but by the mayor as “response to strong feedback” , Geelong’s council voted to spend AU$2 million dollars to remove the bike lane project (which had cost AU$8 million to build). The mayor explained the decision by saying that “it’s clear our community is frustrated with traffic congestion” and the lanes were “causing too much traffic congestion”. In one of many ironies of parking, when there aren’t enough cars the solution is to get more visitors with more parking. And when there are too many—i.e. congestion—the solution is, again, more parking.

(1/2) These changes are modifications to the Green Spine in response to strong feedback. It’s clear our community is frustrated with traffic congestion along Malop Street, and as their elected representatives it’s our duty to respond. The bike lane will remain on the south side. https://t.co/YV0dSxqcve

— Geelong Mayor (@Geelong_Mayor) February 25, 2020

The Geelong council voted against keeping the Green Spine, and for reintroducing parking. But in an unusual move, the state government intervened to prevent Geelong council from removing the Green Spine. The state roads minister this time deployed the Road Management Act to keep the “award winning project” in place and prevent its “reckless” ripping up.

Putting Malop Street in context, the 200-metre strip would have fitted perhaps 50 parking spaces. The council indicates there are “more than 4700 off street car parks and 5400 on street car parks in Central Geelong”. Thousands of spaces are not enough when bikes have taken the place of somewhere less than 1% of that space. Deposed Geelong mayor Darryn Lyons ran for office in 2018 with the platform “Free Parking and More Parking”—boasting that “when I was Mayor I delivered free parking and if elected I will lobby council and state to make sure Geelong not only has free parking but that we have more parking”. In the wake of COVID-19 this, too, has returned to Geelong—as a “COVID support measure” Geelong has introduced “further incentive for people to enjoy the variety of shopping, dining and cultural attractions in central Geelong” via free car parking at least until the end of 2020. To what benefit remains to be (and will probably never be) tested.

Malop Street Green Spine won a Landscape Architecture Award for Civic Landscape at the AILA Awards 2019. Image: Drew Echberg

Malop Street by Outlines Landscape Architecture provides more footpath space for pedestrians and a safer bicycle lane. Image: Drew Echberg

The Green Spine project was almost demolished (for a cost of $2 million) to reinstate car turning lanes. Image: Drew Echberg

“Get Born…”

As I write this, my own future unfolds within the parameters of COVID-19 policies and car parking. It even shifts in its possibilities along eerily similar lines to Victoria’s cities and streets. I am nearly nine months pregnant, and due to give birth any day now. When my pregnancy started, I lived in an inner-city Carlton apartment, and intended to have the baby around the corner at the Royal Women’s Hospital. But when COVID-19 restrictions started I relocated to what was previously my holiday home of 12 years, in country Victoria, intending to wait the restrictions out somewhere with a garden. But as restrictions escalated, they increasingly cleaved Melbourne from regional Victoria. The limits on hospital visits and other tightening conditions increased over the months and ultimately, I officially ‘decentralised’ to have the baby in Bendigo. We have left our Carlton apartment (and its car park) empty for months, as bereft as the streets that surround it. The small country town I live in now was recently advertised as “a great town for these testing times, a very safe place to live”.

Meanwhile, an amazing amount of the information provided to me for attending the hospital to give birth is based around parking the car I do not have. A five-minute introductory video to the maternity ward spends the better part of a minute setting out the various options for parking my presumed car—in one deck, or another, or nearby. To ‘get born’, in the imperative of Bob Dylan’s Subterranean Homesick Blues (“get born, keep warm, short pants, romance…”) is to be born into a world where the main objective is to not get COVID-19, and to be born into the safe enclosure of a car.

Trying to communicate the idea of not coming to hospital in a car and parking is, especially in COVID times, no mean feat. With only one visitor allowed, I should park downstairs, and keep my things in the parked car, and when I leave (in the parked car), I should have my car capsule ready. A list of “essentials for mum and baby” starts with “car capsule” and “sun shield (for car)”. I think back to my own childhood, the hours spent waiting in supermarket car parks, and wonder sometimes if this was prophetic. And I think of my present, in which I hear every imaginable reason why more free car parking is (or at least, hypothetically, could be) the only or fairest solution to a given planning or transport question. And the certain look that people give when I say I did not drive somewhere: the feeling that a person without a car is somehow obscenely reduced.

At the same hospital-meets-car-park, waiting in line (masked, in spaced rows, and amidst the accoutrements of security and temperature monitoring cameras staving off the threat of coronavirus) I overheard discussion of that “tragedy in Kangaroo Flat”. Looking it up later, I read of a two-year-old boy who “wandered” onto the road where he was struck and killed by a car. Cars, whatever else they are to people, are killers. The single largest danger to children, including my own child, will be a world made for and of cars.

Some risks are managed by governments, others are fostered by them. I cannot have visitors, or a bath, but my car (if I had bought one—though I find I am at pains to point out that I can drive, but choose not to) is, in principle, free. And while various constraints on personal liberties—such as freedom of movement—have been tolerated by most in the interests of controlling coronavirus deaths (at least, in a throwback to Australia’s penal past, by most upon pain of police retribution), the line is drawn at the idea of restricting or paying for parking. Car fatalities have a nominal ‘target zero’ but are routinely around 1000 per year in Australia.

In the book Movie Towns and Sitcom Suburbs, Stephen Rowley contrasts the real world of the American suburban landscape with the idealised small-town squares of movies like It’s a Wonderful Life. He points to Back to the Future (1985) and the changes evident in the town centre between 1955 and 1985 as one example. The 1955 scenes embody “the traits of the classic small town, as well as the optimism about a suburban extension”. But by 1985 “the town square has been transformed into a stark image of a run-down old town centre, neglected as retailing has moved to suburban malls and roadside strips” and “most tellingly, the lawns at the centre of the square have been replaced by car parking”.

Back to the Future is rare for commenting (subtly) on the urban parking condition—more commonly in the imagined worlds of cities, the protagonists drive but have no trouble finding parking. They pull up at the front, jump out, and seamlessly continue. The future (indeed, most versions of the fictional present) is usually somewhere where parking issues have disappeared—whether through flying cars, or seamless transit-like cars, or a post-apocalyptic vision of hell where there is, nonetheless, no traffic. Only darkly comedic or social-realist programs will show car parking at foreground, bleak and sometimes overwhelming for the defeated character. Think of Seinfeld, the “show about nothing”, about banalities, which features several parking-based episodes, or of Fargo, as the antagonist chips with anger at the frozen windscreen of a parked car, or Planes, Trains and Automobiles, where Steve Martin’s character struggles hopelessly across a vast airport car park.

Another line from Dylan’s Subterranean Homesick Blues is “Don’t follow leaders, watch the parking meters”. This is quoted as epigraph at the front of a biography of Hannah Arendt. Whatever Dylan meant by it, in the context of governance and Arendt the intended injunction is to pay attention to the overlooked details of bureaucracy. It is these banalities that shape our rights and our lives more directly than do the politics and promises of the future—or in this case, future city—that allow us to ignore reality. In The Origins of Totalitarianism, Arendt wrote that “there is hardly a better way to avoid discussion than by releasing an argument from the control of the present and by saying that only the future will reveal its merits.”

Might Arendt’s “banality of evil” apply to the banality of parking policies? Not evil, perhaps, but much of the damage of the automobile age has been ushered in by the good will of bureaucracy. I think also of Bertrand Russell’s possibly apocryphal story of taking nitrous oxide (laughing gas) and chasing the profound sense of knowing “the secret of the universe” that the drug induces. This sense of awareness, alas, was always accompanied by physical inability to move or to remember what the vision was. With great effort, Russell wrote in 1945’s A History of Western Philosophy, the man (presumed to be Russell himself) trained himself to scrape pen to paper and finally “wrote down the secret before the vision had faded”. That scratched vision turned out to be: “a smell of petroleum pervades throughout”.

Russell used the story to illustrate the deceptiveness of insight—but having studied parking for several years, I tend to think of it as prophetic. Competing visions for a future city appear and recede; but, always, a smell of petroleum pervades throughout.

[This is part two of a series by Elizabeth Taylor on the role of cars in city design, culture and planning. Find part one here.]

Elizabeth Taylor is a Senior Lecturer in Urban Planning & Design at Monash University. Taylor’s research explores links between urban planning, housing markets and locational conflict. She is the author of the book Dry Zones: Planning and the Hangovers of Liquor Licensing History (Palgrave Pivot 2019) and the co-host of the podcast This Must be the Place.