Street fight: Car parks, COVID-19 and the future of urban retail (part 1)

Cars, parked or moving, define our High Streets, at a heavy cost in space, health and lives. In the wake of the pandemic, some see an opportunity to reimagine how our CBDs function, with more space for people and less for cars; others are calling for a car-driven recovery. A bitter battle looms.

In the daily theatre that is Victoria’s coronavirus press conference, the topic of car parking has twice ranked mention as bit player. First, in mid-August, in the wake of public outrage over news a hospital doctor had accrued a parking fine, a state government directive was announced preventing local governments from enforcing parking meters or time limits. A few weeks later, both Melbourne Lord Mayor Sally Capp and Victorian Premier Daniel Andrews talked up plans for “London and New York” style outdoor dining and drinking, with visons of city hospitality venues taking over curb (street) parking in a bid to lure visitors back to a ‘COVIDSafe’ Central Business District.

With restrictions still in place, city streets are empty for now—bar police and the happily parked cars of doctors and construction workers. The dormant street serves as a blank slate onto which ideas compete for the reimagining of a future city. On the one hand, there is the recasting of street parking spaces into trendy summer hospitality venues or pop-up art installations; or the overnight transformation (in the vaunted style of Paris under mayor Anne Hidalgo) from car to bicycle-based streets. Like perfume advertising, the pedigrees of planning ideas are often given as London, Paris or New York—of which Andrews reported “they have used the footpath, the curb side parking, and taken public space and turned it into pop-up cafes, restaurants, bars”, and so in Victoria “that is what we will do. We will change the way the city operates, and the suburbs and regional cities.” In re-election campaigns, Sally Capp likewise promises a range of initiatives with the goal of “re-opening and revitalising the city” and “getting the city back in business”.

On the other side of ideas for the future city are scenes, in throwbacks reminiscent of American ‘drive-in churches’ of the 1950s, of public events conducted to an audience of parked cars; and then there are the many cities and towns promising the ‘golden ticket’ of free car parking. They do so with renewed vigour (calls for more and freer parking being fairly constant since the arrival of mass motorisation in the early 20th century) but this time in the hopes of enticing back a public presumed newly repulsed by public transport and inclined only to travel in the hygienic surrounds of their own vehicle. In the scramble for a post-COVID recovery Adelaide, for one, is to host a “happy driver’s month” in a “plan to lure more cars” and “encourage those people back into the city where they will support our businesses”. Other Melbourne mayoral candidates have proposed a “free parking push to lure shoppers back to the CBD”, including one policy that “would cost $10 million but would be invaluable in attracting shoppers back”.

That last statement hints at an odd truth about parking and retailing in the planning of Australian cities—that although the offer of ‘free’ parking to the driver is paramount, behind the scenes lie decades of efforts and millions of dollars spent in fostering this illusion.

In the novel Crash, writing of the hybridisation of car and body, JG Ballard wrote “we live in a world ruled by fictions of every kind—mass merchandising, advertising, politics conducted as a branch of advertising…we live inside an enormous novel”. The novel, the fiction, of the car is that it is free, and that convenient parking for it materialises naturally. Parking accounts for large swathes of urban and public space and so can represent opportunities for change—but it also buffers the dream of automobility. Moments of crisis prompt reassessment of parking, but any discussion of change shows something more personal and political is at stake.

Hence the view that there is something fundamentally immoral about health workers paying for parking. And why one of my transport contacts, like many who have worked in the field long enough to be jaded about just how serious a political issue even one parking space can be, warned recently, “Think the premier is getting a hard time from people because of the lockdown? Just wait until he tries taking their parking spaces away”.

“Parking spaces should not only be adequate in number”

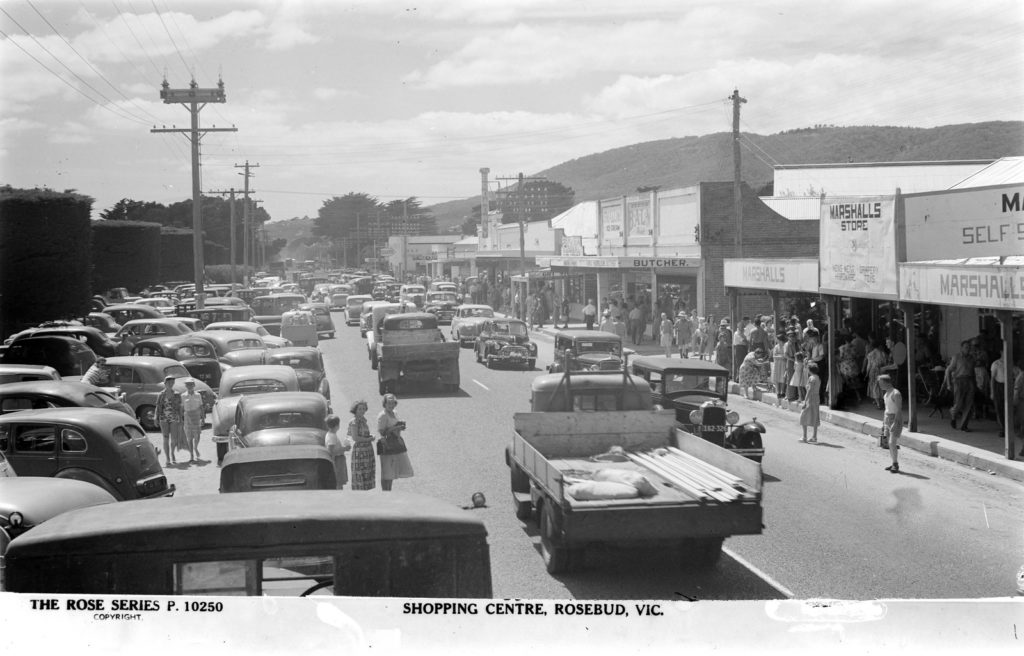

COVID-19 discussions are the continuation of tensions around public space, retailing, and car parking that have been playing out for decades in Australian cities. Since the arrival of mass motorisation in the early 20th century, Australian cities have been redesigned to accommodate cars (and, specifically, their parking) or have been newly built around the provision of ample ostensibly free parking. Despite being imagined in perpetual motion, cars are—in an apparently verifiable calculation—stationary around 95% of the time.

Since the car arrived, it has promised unencumbered personal mobility and an unfolding future melding freedom with machine. As in Le Corbusier’s “Radiant City” and other modern visions of the future city, from architecture to science fiction, it is easy to imagine a future of cars in motion—with us in them, sometimes in flying form. Imagining the immense spaces of car parking required to store cars is a less enticing design proposition.

Typically, the sycophantic task of providing car parking is left to city planners and traders associations—proposing underground or multi-deck car parks, or mechanisms for requiring ‘enough’ parking, to somehow solve the puzzle that car parks are actually very large (around 20 square metres per space) but considered essential to enticing, or ‘luring’ (so often this word—as if they are exotic animals) the consumption power embodied in the car. In some downtown US areas, over a third of the whole surface area is occupied by car parking, which nonetheless manages to disappear from public consciousness except for the brief moment of looking for a space. Parking, as recent scholarship on its role in cities notes, is expected but unnoticed, forgotten as soon as it is found. Any reader of Donald Shoup’s The High Cost of Free Parking in effect swallows a parking pill, to be burdened with forever seeing the acres of asphalt parking space that others are oblivious to.

For decades, planners have pursued the Sisyphean quest of integrating yet more parking into the city, yet never allaying fears of shortage. The 1954 planning scheme for Melbourne, for example, sought to reshape city retailing around the need for parking in two key ways. Older shopping strips, built before the car, represented “the formidable problem” of finding parking. Planners worried that these strip centres would languish and die if more and more convenient parking were not retrofitted, as:

It is becoming generally recognised that no matter how attractive a shop or a shopping centre may be, it will not attract the customer who uses a motor car for shopping unless adequate parking facilities are provided. With the growing use of cars, this problem is becoming increasingly acute, and in future must have a great influence on the prosperity of shopping centres and as a consequence on their planning. Parking spaces should not only be adequate in number, but if they are to fulfil their purpose properly, they must also be located convenient to the shops because shoppers do not want to carry their purchases a long way to their cars. [link]

In response to such concerns, Melbourne’s older retail strips were remodelled via demolitions and special rates projects to integrate significant areas of surface parking and of multi-storey garage parking. The Melbourne suburb of Coburg, for example, has roughly 1000 surface level parking spaces set in blocks either side of Sydney Road. Despite the long and largely successful efforts of trader groups to build or to get councils to build off-street parking areas, however, it remains the elusive on-street (curb) space that promises retail salvation. Hence (as detailed below) it is Sydney Road itself that still forms the battleground for urban change. It is the imagined space ‘just at the front’, the perfect ‘lure’ to the passing car, that retailers prize above all other space. Over the decades, even as older strip shopping centres integrate more parking, the fight over street parking rarely abates.

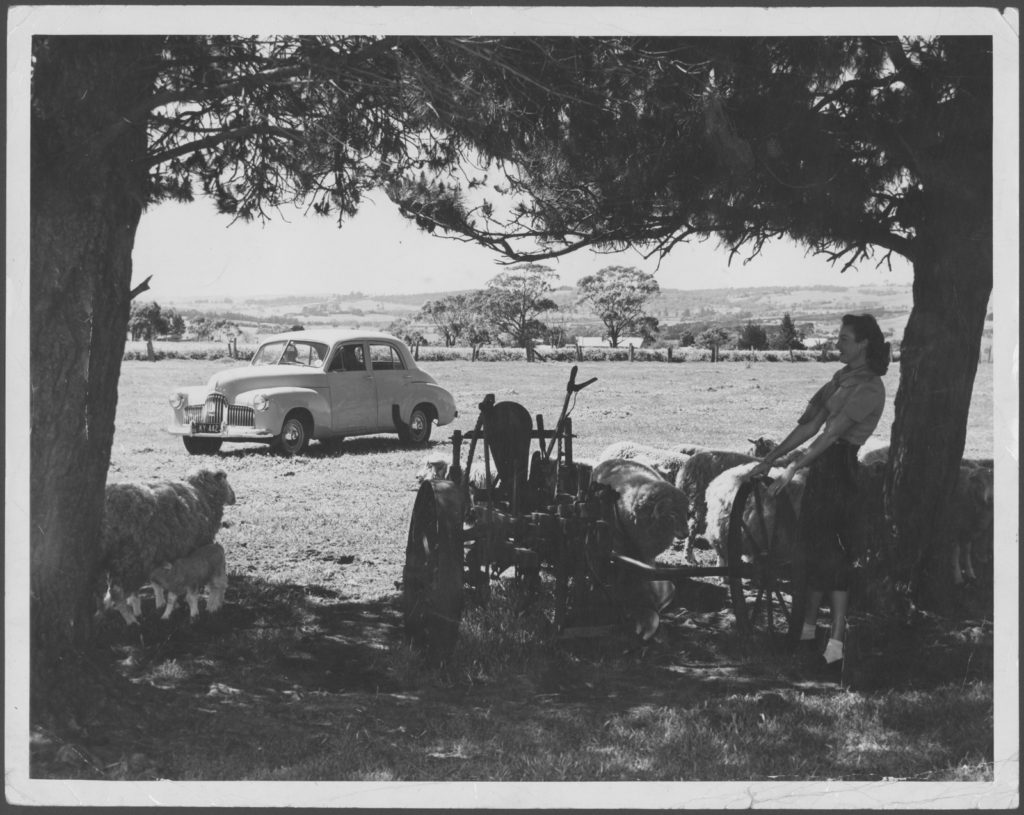

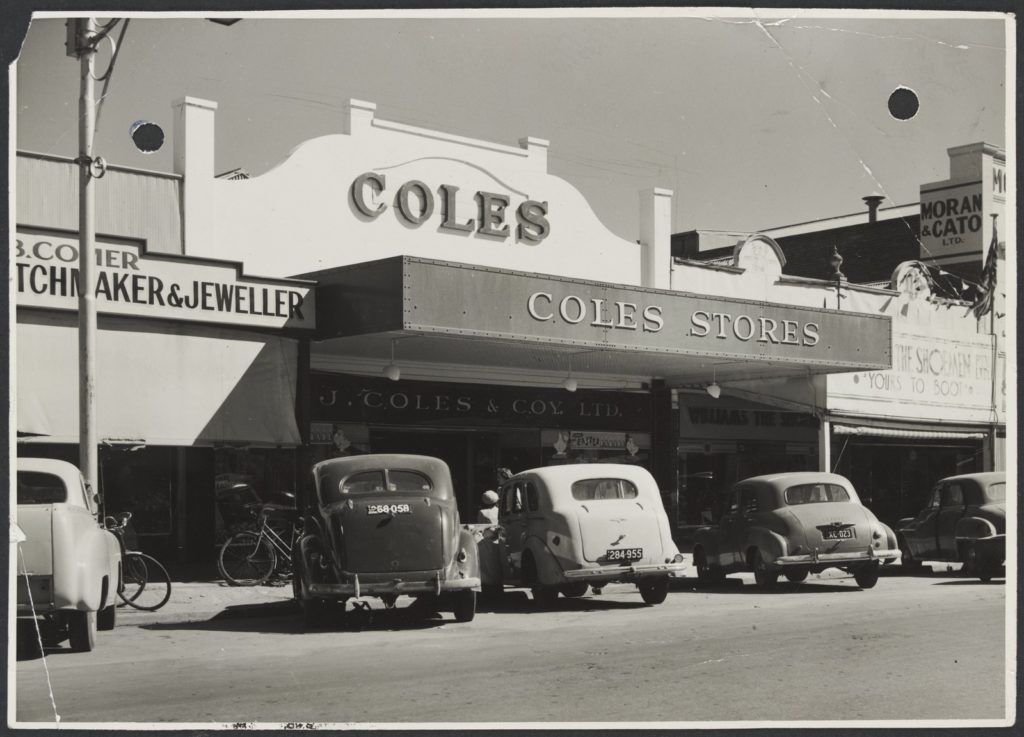

Also through the 1954 Melbourne planning scheme, meanwhile, newer suburban centres were specifically modelled on the new American shopping mall—an internal pedestrian retail space surrounded, in fact dwarfed, by oceans of surface car parking. Victor Gruen conceived of his highly influential shopping mall as recreating the pedestrian feel of European town centres, with cars kept outside. In a 1950s Melbourne seeking to plan around the rapid increase in car ownership (and associated demands for parking) a Los Angeles, not New York, planning pedigree of futuristic motorisation and malls was to be boasted of.

In 1953, the Town and Country Planning Association and the City Development Association invited Charles B Bennett, Director of Planning at the City of Los Angeles, to present in Melbourne. A puff piece on his visit, “Planning of a city for good living”, illustrated “a parking station for 2000 cars, in the heart of a city, but away from the traffic lanes”. Approvingly, the article described how “Los Angeles has developed principally during the ‘automobile age’”, noting “Los Angeles residents enjoy the freedom of movement made possible by driving their own cars”. Bennett praised the use of zoning and master planning—“the best things in life are the result of planning on the part of someone who had vision”.

Part of planning for the car was the use of minimum off-street parking requirements—site-based requirements for each development to provide parking to meet anticipated needs. As well as including enticing images of American shopping mall car parks, this was one idea that Melbourne planners adopted directly from Los Angeles: of the new policy (much of which still applies, albeit in more complex form) the scheme authors conceded that “by contemporary American standards this provision would be inadequate, but it is much in advance of what is available today in Melbourne.”

“Make room for parking!”

As a dense central area developed before the arrival of cars, Melbourne’s CBD has its own history of attempts to reconfigure to cater to parking. Historically, Melbourne CBD traders have been active in seeking to add commercial parking to the CBD, and to deflect on-street parking restrictions, in efforts to compete with suburban malls. The politics of this in the 1950s is described in Graeme Davison’s Car Wars (2004). Through the mid-20th century, Melbourne CBD trader group the City Development Association (CDA) proposed more kerb parking, parking decks, sponsored visits from Los Angeles planners and traffic experts, and printed pamphlets and articles urging new ways to fit parking into the central city.

In one article headed “Parking space ‘must be found” (1954) the CDA warned that “Melbourne’s central business area was facing the gravest threat of its history” if new measures to manage competition for street parking were continued—“if the ban on kerb marking is made general, not only will thousands of motorists be completely frustrated, but business will decline”. In 1955, foreshadowing the COVID era preoccupation with health worker parking, an item headlined “Parking forcing doctors out of the city” warned parking troubles were “forcing professional men out of the city into the suburbs” and would “force business out the same way unless prompt and drastic steps were taken”. And in 1956, with a strident heading presaging 1966 dystopian sci-fi novel Make Room! Make Room! (later adapted into the film Soylent Green) “Make Room for Parking!” the CDA urged “that post boxes, fire hydrants, taxi stands and other service installations be grouped together in an effort to create more kerbside parking space”.

Davison charts the futuristic visions of a Melbourne CBD that managed to balance cars with the central city. Later, in 1965, the RACV unveiled plans for a “split level city”, with layers of parking beneath the Melbourne CBD. Robin Goodman studied the role of city retailers in Melbourne in the early 1990s, finding “a persistent discourse within Melbourne that…retailing within the CBD will inevitably decline under competition from suburban shopping centres”. Goodman tracks this fear of decline over decades, with strategies for marketing and responding to that threat since the 1950s. COVID era headlines, “Melbourne’s CBD faces $110b wipe out”, “Inner Melbourne economy tipped to suffer $110b hit over five years”, reprise these fears with new urgency.

Long before COVID-19, Australian retailers feared going out of business on account of numerous threats (online trading one of the more recent). Another Melbourne councillor, Nicholas Reece, recently penned an opinion piece for The Age entitled “Death of Melbourne’s shopping strips is an opportunity for renewal”. The list of strips he gave with high vacancy rates encompassed those with ample parking, and those without. Even the standalone malls built for the car now struggle with tenancies and viability—as the ABC discovers in “Shopping centres feel the pinch as retail speeds up move to online”.

Australian retail real estate values have been steadily falling and businesses are shifting away from ‘bricks and mortar’ to digital sales. Onto this has come COVID-19 closures and more downturns (hand sanitisers and home electricals for a newly housebound populace notwithstanding).

In the US, many suburban malls have closed—a phenomenon captured in the grass-festooned car parks of ‘dead malls’. Dead malls have been linked to a lack of interest and demand in the face of the global financial crisis in 2008, and increased competition from online retailing and a resurgence in town centres or downtown areas. Mall owners and financiers have sometimes looked to traditional high streets as models, with efforts to recreate hospitality focused outdoor spaces.

But a variety of winds buffet retailers. A lack of evidence either way sustains the belief that parking is the panacea for retail ills. As Reece wrote, “many of these businesses were already struggling as a result of the shift to online shopping at the expense of bricks and mortar retail. COVID-19 has turbo charged this trend”.

The tribulations of the retail sector matter more broadly to cities, for one thing because retailer fears so often shape public policies. A focus of this fear and influence has been, both before and during COVID-19 debates, an assumed equivalency between ample free car parking and ‘visitors’, with ‘visitors’ code for ‘spenders’ and in turn, for retail viability. Viable retail serves as both proof of and marketing for a city’s success. Retailers, imagining their impending end, cling to the idea parking is the one true hope. Never more so than in a crisis, many can’t imagine (parking) space as anything but a commodity for their business.

Retailing has a fundamental role in how we imagine public spaces. Unashamedly or unconsciously, when politicians speak of ‘revitalising’ centres a fundamental precept is that public spaces function to support retail businesses. Outdoor space, for dining and hospitality, tends only to be seen instrumentally, in terms of its value in attracting spending. And history shows Australian retailers (especially in local collective form, as traders associations) embody a characteristic of capitalism itself: uniquely preoccupied with fearing and foreseeing its own end, while being unable to imagine any alternatives (to paraphrase Mark Fisher).

As one example, in 2012–2014, plans for accessibility and speed upgrades to Melbourne’s Number 96 tram route sparked ‘neighbourhood spot fires’ of parking fears along its route from St Kilda’s Acland Street to the Nicholson Street ‘village’ of North Carlton and East Brunswick, where a “save Nicholson Village” campaign negotiated to retain car parking spaces. A consultation report for the tram project suggested that while a pedestrianised Acland Street was “widely supported by the community and the City of Port Phillip, there were strong concerns raised (in particular by the St Kilda Village Traders Group) that this would impact local businesses in Acland Street”. Acland Street traders warned that the removal of 50 parking spaces would “sound the death knell” for the strip, and held a funeral for the loss of on-street parking that the tram upgrades involved. The changes to Acland Street did ultimately go ahead—I would report on how it turned out, except that with St Kilda (as with most parking changes) there is a fundamental lack of systematic, before and after studies of retailing impacts (although the City of Port Phillip did prepare this evaluation report 12 months after completion). In the midst of online retailing and COVID-19 downturns, it is left to sharing selectively framed pictures either supporting or disproving impacts.

While retail traders’ concerns so often underscore opposition to changes to parking, there is weak or contrary research evidence that parking influences retailing viability. Available studies suggest that the number of drivers, and influence of parking, is overestimated by traders. Some studies suggest retail spending is higher by pedestrians and cyclists, and that spending is increased by road space reallocation to parks and other spaces. Barbara TH Yen and others (2015) found that in restaurant precincts in Brisbane, store owners significantly over-estimated the proportion of customers coming by car, while underestimating pedestrian and other traffic. Alison Lee and Alan March (2010) found in a study of Lygon Street in Carlton that while bike parking was allocated a small amount of space, it generated significantly more spending per hour (AU$31) than car parking (AU$6). However, there are few observed behavioural studies or large-scale sources of evidence over time.

Parking and retailing remain a realm of received wisdom, and anyone’s novel to write.

[This is the first part of a two-part feature on car parking’s influence on the design of our high streets. Find part two here]

Dr Elizabeth Taylor is a Senior Lecturer in Urban Planning & Design at Monash University. Taylor’s research explores links between urban planning, housing markets and locational conflict. She is the author of the book Dry Zones: Planning and the Hangovers of Liquor Licensing History (Palgrave Pivot 2019) and the co-host of the podcast This Must be the Place.

[This article was modified Friday 2 October 2020 to include a link to the City of Port Phillip’s Acland Road pedestrianisation evaluation report — Ed]