Work in progress: the tropical garden that can’t be rushed

Landscape architect Shaun Walsh reveals the joys (and hard work) behind a garden that he started planting twenty years ago. And he’s only just getting started.

CEO of South Bank Parklands and Roma Street Parklands, Shaun Walsh, is both a town planner and landscape architect. He is also a compulsive gardener. Twenty years ago he purchased an 11-acre property with his partner at Cooran, on the northern edge of the Sunshine Coast hinterland and surrounded by State and National Park rainforest. Shaun is a native Queenslander, born in Ipswich and brought up in Townsville and Brisbane, with family at Kin Kin and scattered around the Gympie area. His first job as a graduate town planner was with Noosa Council. The original council chambers were in nearby Pomona, but moved to the coast in the 1980s when the boom took over.

Shaun insists that his garden as a work-in-progress. His joy in gardening lies in bold experiments, to achieve his visions. There is no big budget and the work has all been done by himself using found objects, and with largely self-propagated plant material. It is not about showing off a completed designer landscape, but sharing the gradually ever-more apparent possibilities for new experiences of beauty and happiness.

Jo Russell-Clarke: When you bought the property, were you looking at it with an eye to its gardening potential?

Shaun Walsh: If I’d been brought up on the land, I would have been the one to stay on as a farmer. I want to embed myself into a landscape over many decades and watch things grow. Both my grandfathers were farmers, and I think there’s probably something genetic there. I just have a thing for soil and land.

JRC: You were familiar with the area and its weather patterns, while visiting family in the past. Have things changed over the time you have lived there?

SW: When we moved here, there was definitely more consistent rainfall and temperature. Over time we’ve had much higher and lower extremes of temperatures and also much more variability in rainfall. Sometimes we’ll get five inches in a day but then no rain for 10 months. Twenty years ago, when it was dairy farm and covered in kikuyu, there was consistent rain from south-easterlies and storms. We’ve seen a change in the pasture, with kikuyu rapidly dying out and being replaced by other pasture grasses. Gardeners by nature are very observant people and so are farmers. We are seeing climate change happening in this landscape.

JRC: What is the longer history of European settlement and agricultural change in this landscape?

SW: This area was one of the communal land settlement areas of Queensland, part of the New Australian Movement under William Lane. At its peak, some outrageous figure, like eight percent of Australians, were part of this movement. It was a reaction to squattocracy and the lack of access to land prior to federation. In our local area there was the Protestant United Group and another called the Woolloongabba Exemplars who settled in and around Pomona. While the settlement failed within 10 years, displacing the Indigenous population, their efforts led to the establishment of European agriculture in the area in the early 1900s.

JRC: Why are you a ‘compulsive gardener’? How did that come about?

SW: They say that when you retire you return to the thing you most enjoyed as a kid. Gardening as a kid made me very happy. During school holidays my grandfather and I would weed the lawn with a dinner fork. I’m not joking. My brothers and sisters and cousins detested it. I liked it! And then my mother was one of those natural, free-form gardeners, with cuttings in jars all over the place. At that time we were in Cleveland, which had very good soil. It was the original salad bowl of Brisbane, where you could stick anything in the ground and it would grow. It was perhaps the fact that I had success with growing things at a young age that got me hooked.

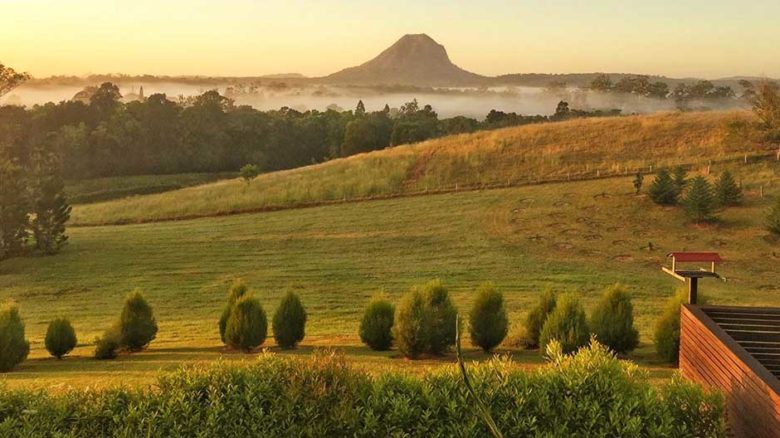

Garden walk, looking to house and Mount Pinbarren backdrop

View of Mount Pinbarren from the verandah at dawn.

The landscape shifts and changes over the course of each day.

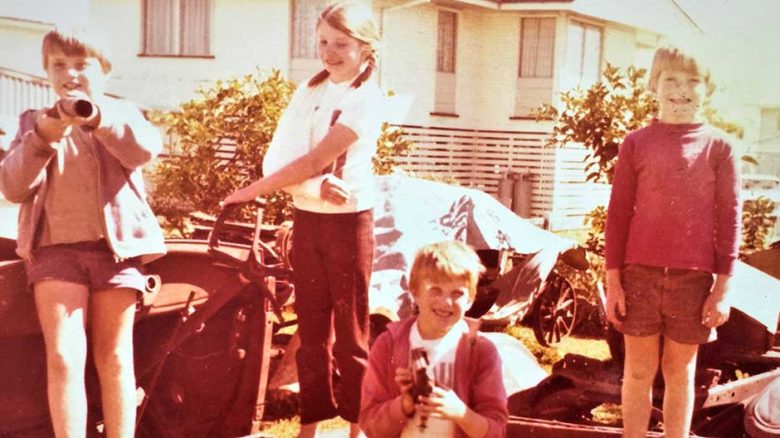

Walsh was brought up in Townsville, with a free-form yard. Here playing in 'Dad’s vintage car collection'.

JRC: Many of us would say we enjoy gardening, but draw a line at how much effort it can take. Yet clearly you seem to like the work!

SW: We recently had Costa (Georgiadis) at Roma Street Parklands. A member of the public asked him about his Gardening Australia show, pointing out that he doesn’t talk about the really hard work. Lifestyle shows do not focus on that. Gardening is physically demanding and full of disappointment at times, but anything difficult is all the more worthwhile, when you do have success. People also don’t talk about climate. We lived in Hobart for a while and gardening was easy. It’s temperate to cool. You can garden all day. And weeds are nothing in Hobart compared to tropical and subtropical weeds.

JRC: You have an interest in native plants and using them in gardens, in more than ‘bush garden’ ways. Is this a curiosity about what native plants can do, or something more?

SW: It’s a few things. Firstly, I am not a native plant zealot. The Brisbane Queenslander we lived in was full of colourful subtropical exotics, such as crotons and bromeliads. They were really garish and really beautiful. In Hobart we had a full cottage garden, with roses and flowering groundcovers. But this garden is different. I really set myself the challenge of conjuring up the same emotional connections we have with a certain type of garden, as European descendants, but just using a palette of native plants?

I think we’ve lost the way a bit in terms of how we appreciate our native flora in cultivated landscapes, compared to conversations we were having 20 years ago. Maybe the scrappy bush garden did us a disservice. We didn’t look to the further potential of certain species. If you look back, the first native plant we exported was the paper daisy. Sold as straw daisies in the early 1800s, it’s now a common garden plant in Europe.

JRC: Was the land here a clean palette when you first got it, or were there remnant portions of the indigenous landscape that were kept?

SW: There was just one gum tree and one fig tree across the eleven acres. The original framework planting of hoop pines we did eighteen years ago. Hoop pines around homesteads in Queensland are an iconic planting. They are site markers. Navigating in the landscape before there was a well-defined road network, you could find the homestead by a dominant growth of pines. There are some bunya pines, but I like the feathery foliage of hoop pines. We have frontage to a creek too, with very good rainforest just outside our boundary. So we put in an additional 50-metre riparian belt of endemic species, with the assistance of Landcare. To see it now, it looks like it’s always been there.

JRC: And is that bringing back the fauna as well?

SW: Yes, one of the things we are noticing, as the whole garden develops, is how much fauna we are getting. Birdlife, kangaroos, bandicoots, echidnas. And we also have a great flood predictor. We’re on Pinbarren Creek near the Six Mile, which is a major tributary to the Mary River, so we have cracker floods. We’ve had really large native turtles come up through the paddocks a few hundred metres from the creek, to lay their eggs in the garden. The first time it happened it freaked us out. The following week we had a major flood.

Secluded swimming terrace with young hoop pines starting to become a landmark

Front stairs with mountain backdrop

Reconfigured front stairs and landscaping

View from dining pavilion into mass plating palm of doranythes palmerii lillies

Hedge of luminous podacarpus (left) and pandorea vine, bangalow palms and juvenile hoop pine (right).

JRC: Can you describe a journey into the garden?

SW: To start, we turned our back to the road and I’ve planted what I call the shrubarethrum as a screen. I’ve experimented with species not traditionally associated with shrubs, like native Croton insularis, Podocarpus elatus and green kamala. They create a moment of drama when you come through our gate and see the view.

The planting along the entry is large-scale and simple: silky oak and flame trees with an under storey of clipped Cissus antarctica kangaroo vine, which performs like ivy. So you get a clear mid-storey sight to the house, through the trees. I have a procession of clipped Callitris columellaris, Queensland coastal cypress. Eventually I’d like it to be a bit Tuscan. I’m interested in the juxtaposition of Australian and South-East Queensland species, in non-traditional relationships. The bunya grove I have coming up has a foreground of Pandanus pedunculatus, which you never see together. The hoop pine grove has Macaranga, so you end up with these big green lollipop leaves and round trees against the pointed hoop pines. The contrast brings out the best in both.

The latest project I’ve been working on, is a big grove of native finger limes. In the wild they’re evocative of an olive grove. The kangaroos love them. Of all the fauna damage I’ve had over the years, they are the worst. It’s not the eating – they just seem to love rolling on them. I don’t mind the wildlife damage. Yellow-tailed black cockatoos come in and decimate the swamp banksias every year, but there’s nothing more spectacular. It is better than any flower I’ve ever seen.

Around the house is a series of planted courtyards. I don’t like big forecourts of cars. I do everything I can to get cars out of the landscape. In my professional life, I have stewardship and leadership but not necessarily control. Luckily, with your own garden you can do what you like!

JRC: We don’t hear much about gardening from landscape architects. Why do you suppose landscape architects are reticent to talk about the garden as a sensorial, designed space?

SW: It’s a quandary. Architects embrace houses – the domestic form of architecture. Harry Seidler was as proud and well-known for his houses, as high-rise and major commission work. Why aren’t landscape architects the same? It’s actually the general public’s emotional connection to gardens that is the gateway to landscape architecture appreciation. We shouldn’t think it inferior to talk about gardens. It isn’t a lesser art. Perhaps it is part of an old inferiority complex, in thinking that engineers and architects know better. That’s just rubbish. Whenever we’re engaged in a discussion with other professionals, we must get in there, boots and all, with confidence in the value of the expertise we bring. I don’t distinguish between gardens and landscape architecture. I think it is all landscape architecture.

JRC: Perhaps it could also point to a declining interest in plants, as a key material of our discipline?

SW: That could be right. Planting can be seen by some, as the dressing to a space, rather than instrumental to its success. It’s important to remember too, that gardening is a process. My own garden is very much still in progress – that’s the joy of it. Perhaps that’s the distinction between gardening and landscape architecture. Gardens are allowed to change. There are other constraints and expectations with public landscapes. With my own garden I am prepared to think 10 to 20 years ahead, not two or three. I love watching it grow. It gives me great joy. I can sit on my verandah and say to myself, “Gee, that’s doing really well!”

–

Dr Jo Russell-Clarke is a senior lecturer in the School of Architecture and Built Environment, Adelaide University, and a registered landscape architect and Fellow of the AILA.