The inverse high-line: Melbourne’s Skyrail linear park

Does government issue public consultation really give the public a voice? That’s the question urban design think-tank Office posed of the Skyrail linear park project. With the park’s final designs just released, we speak to Office to see if local residents were heard.

Due for completion in late-2018, Melbourne’s newest elevated railway line will remove nine level-crossings, build five stations, and convert “111 MCGs’ worth” of vacant land into open public space. Delivered by the Victorian Government’s Level Crossing Removal Authority (LXRA), the final piece of the project is nearing completion: a 17-kilometre linear park sitting directly under the rail overpass.

Located between Caulfield and Dandenong, the park will be split into seven sections, featuring multi-use sports courts (such as netball, basketball, futsal and table tennis), fitness areas, bouldering units, a RSL memorial and ceremonial space, and 400 new car parks. But with so much of this project riding high (both literally and figuratively) on the aspirations of its users, and the government that serves them, some are wondering whether the authority actually cared about the outcomes of community consultation.

“Some planning bodies just use consultations as a means to reinforce what they’re doing anyway,” says landscape architect Steve Mintern, director of not-for-profit urban planning office, Office. “One of the questions during the consultation period for the Skyrail open space plan was whether or not residents wanted signage… well, of course you want that.”

Above: An overview of the Caulfield to Dandenong Skyrail project.

Mintern, along with Office, took it upon themselves to establish an alternative community consultation option, called Leftunder. While the authority engaged in a sizeable number of direct and indirect consultations, Office argued for an unfiltered and open consultative process, seeking honest input from the park’s beneficiaries.

At various points through the park, playspaces will be accessible to residents and visitors. Image: LXRA.

The park will incorporate mixed-use modes of use for residents and visitors. Image: LXRA.

The park's proposed RSL memorial and ceremonial space. Image: LXRA.

The authority states that the plan allows for 4000 new trees to be planted across the corridor. Image: LXRA.

Centre Road East in Clayton will facilitate a number of different ball-sports. Image: LXRA.

Community ‘lounge’ spaces on Heatherton Road, Noble Park.

“Everyone is going to say that they like trees. So if you ask them a yes or no question about more tree-planting, you’re going to get the answer you want,” says Mintern. “The bigger challenge during these processes is to ask what’s missing from the community. Consultation should aim higher.”

This discrepancy is apparent when you compare the open space consultation findings from Office and the LXRA. While the authority fielded 1573 written submissions, not one articulated the opportunities for habitat development, despite eight percent of those submissions discussing the project’s impact on vegetation. By contrast, one Leftunder resident spoke of the opportunity for Skyrail pylons to include habitat boxes, “preferably for native birds and species other than possums”.

“That idea was a simple translation of a resident’s idea that came about without filling out a survey,” says Mintern. “So we drafted some visuals on what that might look like, which went out to Twitter, and that got aggressively mocked by the anti-skyrail brigade – which is just part of the process. But that’s what consultation should be like, because if you put an idea out into the world, it’s open for criticism. Whether that criticism is positive or negative, it’s valuable either way.”

For the most part, the nature of the criticism surrounding the park stemmed from irrational fears of the “overpass”. One resident, Michelle Bennett, told the Herald Sun that “everyone is concerned about security and safety”. However, the newspaper failed to acknowledge that her suburb of Carnegie sits in one of the safest local government areas in Victoria, with a crime rate of 3896.8 per 100,000 people.

It is, however, easy to understand why perceptions such as Bennett’s continue to linger. Popular culture has cast underpasses as crime-ridden, such as in the Batman franchise, sites for the abnormal in A Clockwork Orange (1971), and reaching back into history, a home for trolls, thanks to fairy tales such as the Three Billy Goats Gruff (1841-44).

A Leftunder consultation box at Carnegie Station. Image: Leftunder.

Folly for a Flyover, London. Image: Assemble Studio.

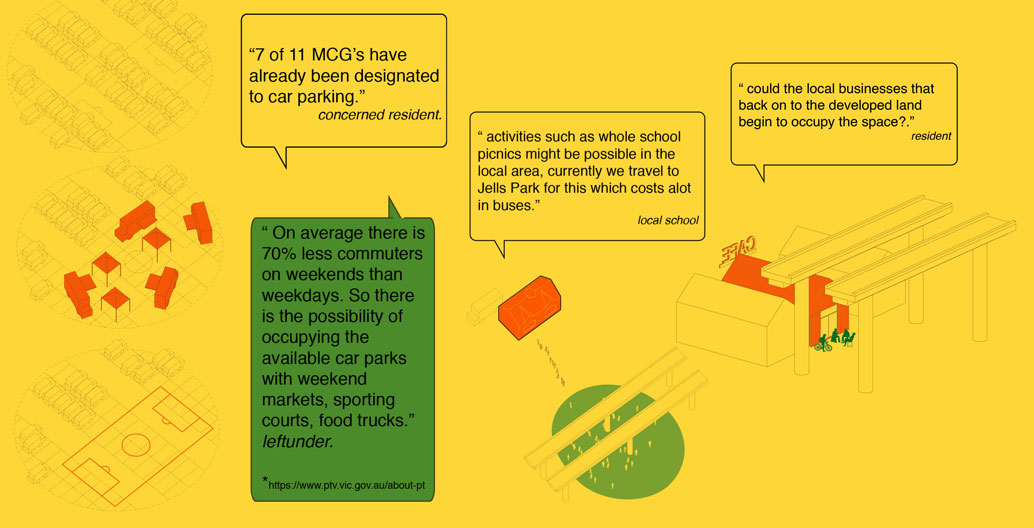

A snapshot of some of the community's ideas when tabled with Leftunder. Image: Leftunder.

Construction staff pouring concrete for the elevated rail deck. Image: LXRA.

The hollow core deck at the Clayton Station. Image: LXRA.

The last beam slotted into place between Clayton and Noble Park, totalling 384 beams spanning 2.8km. Image: LXRA.

“When you look at overpasses traditionally, they have been quite horrible places,” says Mintern. “What’s interesting about the linear park is that it’s a completely new build, so you have the opportunity to bring the community along with you, for them to understand they have the right to ‘good stuff’ to be present in the area.”

In the lead-up to the consultation period, Leftunder looked at the ‘good stuff’ in overpass conversions around the world, charting sites in Europe, the UK, and Canada.

“One of the projects that got the most community engagement was the Folly for a Flyover project in London,” says Mintern. The project, by London-based group Assemble, transformed a flyover on the city’s A12 motorway into a temporary hand-built canal-side cinema. It housed a bar, cafe, and cinema stalls. Mimicking the red Victorian brick of surrounding Hackney Wick, the intervention drew together a team of volunteers to assemble, and eventually disassemble the project. “Because of the temporal nature of the folly, it allowed its creators to test and experiment.”

“Thinking about what should go into the park isn’t something that most residents think about every day. So showing residents some interesting projects, and paring things back from there certainly got them excited,” says Mintern. “Even if you look at the sheer amount of car parks, thinking about what they could be on the weekend, and what they convey after hours, is really valuable. They don’t have to be dead space if you think about them temporally.”

Above: The Caulfield to Dandenong: Community Open Space Expert Panel Q&A

One of the most famous rail-park conversions in the past decade has been New York City’s High Line – a 2.3-kilometre-long elevated linear park. Once a freight line to carry food and agricultural goods through Manhattan’s West Side, it has become a haven for design-doyennes and Instagram’s #archiporn community since being turned into the park in 2014 (having sat vacant since 1980).

While Melbourne’s linear park is unlikely to host the same kind of groundbreaking conversion of public space, people like Mintern aren’t going to sit around and be complacent, given the “two years’ worth” of qualitative data the Leftunder project can continue to provide planners.

“Once the dust settles after the next state election, what happens to the park after that will be really interesting,” says Mintern. “We’re going to continue to advocate for good public spaces. We’re sitting on a massive archive of people’s input and we want a good outcome for these communities – so we’ll have to wait and see once the public actually start using it.”

—

OFFICE is a multidisciplinary not for profit, interested in the urban realm and all its intricacies. As a collective it is responsive and adaptive, collaborating at a number of levels, committed to be socially engaged. Steve Mintern is a landscape architect and OFFICE’s co-director.