Local heroes: small projects with big ambitions for public space

In Queensland, a quiet army of landscape architects in local councils are working to achieve – often within modest means – public spaces with high impact.

The 2018 Australian Institute of Landscape Architects Queensland awards have been announced, with a slew of in-house public space projects by local councils winning accolades. These projects present particular challenges and opportunities, with councils acting as both designer and client to create community-driven places.

Logan City Council, in southern Brisbane, punched above its weight, with two recent in-house projects recognized. The first, Slacks Tracks, won a Parks and Open Space Landscape Architecture Award, while the second, Wembley Link Pathway Public Art, won a Small Projects Award of Excellence.

“Logan is quite a low-socio economic area, it’s not like these designer spots, that are highly looked after,” says Candy Rosmarin, parks design coordinator at Logan City Council. “Our public spaces have to be resilient – the design has to be tight, it can’t be fluffy.”

Palmwoods New Town Square by Sunshine Coast Council, Excellence Award for Civic Landscape. Image: Greg Gardner

Palmwoods New Town Square involved creative community engagement projects. Image: Anita Elliston

Community workshops for new public space underway in Gympie's Smithfield Street. Image: GRC

Locals celebrate the community-led revival of Smithfield Street. Image: GRC

Slacks Tracks, a new linear park and pathway system along the creek corridor, began with an ambition to encourage people to rediscover their creek. Like so many waterways found around the country, the creek had been used as a dumping ground, and, bordered by back fences and industrial development, had a dodgy reputation. To Rosmarin the solution was obvious: “If people knew the creek was there, and they liked it, they’d look after it.”

But how do you get people to venture to a place considered to be dangerous, let alone get them to care about it?

With a relatively small budget – around $600,000 – the design team kept their ambition of getting people to care central to their design tactics. They identified previously undiscovered destinations along the creek and developed a strong language to build legibility in what could be read as “cues for care”, to borrow from Joan Nassauer’s essay ‘Messy Systems, Orderly Frames’.

The design itself may be modest – a painted underpass, way-finding signage, viewing platforms, play features and the odd bit of sculpture – but its striking (and liberal) use of the colour yellow works. Rosmarin sees it as something of a branding exercise to help identify the creek as a safe and welcoming place. “We painted the underpass where people were scared to walk. Just by branding it and giving it that colour, there are now people walking along the track all the time.”

The design team 'branded' the Slacks Creek underpass to encourage people to take ownership of it. Image: supplied

New facilities were strategically placed to encourage people to linger. Image: supplied

Simple design interventions build public space amenity. Image: supplied

The colour and design features are playful cues to help locals rekindle affection for their creek. Image: supplied

New connections are branded in Slacks Tracks yellow. Image: supplied

Wayfinding signs help people create generate new routes, whether for leisure or commuting. Image: supplied

Opportunities for public space collaboration

The project forges key connections into nearby facilities, such as parks and off-leash dog areas. It’s an example of one of the benefits of acting as both designer and client. That is, the potential spin-off effects and ability to collaborate with other council departments. At Slacks Tracks, Rosmarin has been able to coordinate revegetation projects, and make-use of work for the dole schemes to help incrementally improve the creek corridor. It also means the landscape architects can step-in when required and minimise damage from other quarters.

“We had an instance where we had to put a hideous sewer pipe over the creek, and we’ve managed to argue, ‘the creek now has an amenity value that you need to consider’. It’s meant we’ve been able to get funding to improve the amenity further.”

Working within local government allows landscape architects the ability to work incrementally, to see the broader context of the city, identify potential projects and then act when the opportunity arises. It’s an aspect of the work that Rosmarin acknowledges, but cautions that success only comes with persistence. Rosmarin has spent years building the reputation of landscape architecture within council and building trust with the councillors themselves.

“Historically, landscape architects were probably just there to decorate parks or put swings in. We’ve worked hard to raise our profile and we’re now the go-to people when anything about public space is involved. In the beginning we were seeking them out, saying ‘You’re doing that? Well, we need to have input.’ I was probably a bit pushy!”

As for building trust with Logan’s citizens, Rosmarin says a lot of the work is about making sure the community has the opportunity to take ownership of each project. The first phase of Slacks Tracks ran behind a local school and much of the work was about engaging with the school and considering its particular needs. The next section intersects with industrial development, therefore a new set of criteria will need to be negotiated.

Fire signals: Building momentum for public space regeneration

Rosmarin recalls a lecture (“I can’t remember who it was!”) about a river regeneration project that has stayed with her. “Someone asked, ‘if you don’t have enough money to do the whole thing, how do you do it?’ They said: ‘We light fires. We identify one spark and we work on that and make it really nice. The person down the road sees what’s happening and they want more.’ Our budgets are small, so that’s my approach now; I light fires that generate interest.”

Wembley Link Pathway Public Art Project was conceived as a major new pathway connecting the train station into Logan’s civic centre, and local parks and schools along the way. The project had originally been farmed out to external consultants, tasked with a brief that included a public art component. When Rosmarin’s department was asked to document the project, she immediately saw an opportunity, and a potential problem.

“I didn’t want it to become a pathway that had art along it – given the local population, most art installations would have absolutely no relevance to the people using that path.” Working collaboratively with the economic development branch, Rosmarin argued for robust art that would function as “part of the furniture, rather than just being a stand alone sculpture of a bird, or whatever.”

The path itself is punctuated by a series of colourful stripes, representing the flags of the 10 most prominent nationalities in Logan, which were deconstructed and reassembled in proportion to the amount of colour found in each nation’s flag. In places, the colours wrap up around benches, and culminate in the artworks produced by local artists in the form of gateway arbours at two entrances. The artworks themselves are brightly coloured perforated metal sheets attached to the arbours. The artists’ designs were transposed onto the sheets so that the perforations would throw shadows onto the path and create a double effect.

Public Art doubles as a gateway to Wembley Link path. Image: supplied

Seats and pavements feature colours taken from the flags of Logan's most prominent nationalities. Image: supplied

Detail of the art installation at Wembley Link changing the public space. Image: supplied

Projects such as Slacks Tracks and Wembley Link come down to knowing a place well enough to be able to identify its particularities and ensure these are small projects with “ripple ramifications”:

“When we have opportunities to connect to the bigger picture of how we see Logan, these are the ones that have the most connections, that involve collaboration, these are the kinds of projects that we’re always trying to steer councilors and the people who fund us towards.”

When it comes to evaluating each project’s success, for Rosmarin “it’s the stuff that goes unnoticed, but that is being used that has the most impact. Slacks Creek is always busy now. It’s where people go and where people feel safe. Logan Central (where Wembley Link Path is located) is not a particularly safe place, so the fact that people feel safe to use it is my evidence.”

This is not “fancy stuff”, says Rosmarin, who says she’s not driven by a sense of design ownership, preferring those projects where “you don’t feel the hand of the designer too much – it’s the community’s space. I like looking at it, but it’s theirs, not mine.”

A raft of successful projects from this year’s Australian Institute of Landscape Architects Queensland Awards feature collaborative and community-led approaches spearheaded by local government bodies. For example, Sunshine Coast Council’s collaboration with not-for-profit organisation CoDesign partnership seen in the Palmwoods New Town Square Placemaking Project worked to catalyse the discovery of a “unique identity”, according to the awards jury. In regional Gympie, Gympie Regional Council and Place Design Group joined forces to create a pedestrian-focused street with renewed life and economic health.

Reflecting on the winning projects, Amalie Wright, AILA QLD Awards jury chair commended this trend, noting that such projects may not be the easiest to navigate, “managing competing points-of-view can be challenging, but the end result is stronger”.

See images of all the winners from this year’s awards below.

AILA

Queensland Landscape Architecture Awards winners 2018:

Award of Excellence winners:

Civic: Palmwoods New Town Square, by Sunshine Coast Council. Image: Greg Gardner

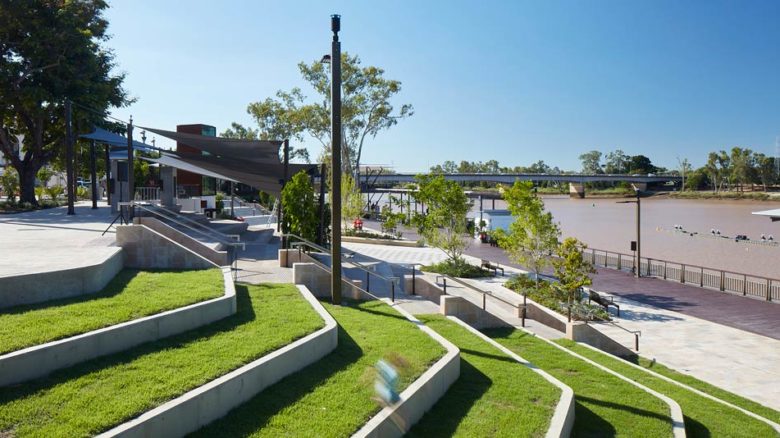

Parks & Open Space: Rockhampton Riverside by Urbis. Image: Florian Groehn

Play Spaces: Centenary Lakes Nature Play by Landplan Landscape Architecture. Image: Andrew Watson

Tourism: HOTA Outdoor Stage by Cusp, Topotek1 & ARM. Image: John Gollings

Landscape Planning: Brisbane Airport Strategy Manual by Tract Consultants & Urban Enquiry. Image: supplied

Small Projects: Wembley Link Pathway Public Art by Logan City Council. Image: supplied

Landscape Architecture Award winners:

Civic: HOTA Outdoor Stage by Cusp, Topotek1 & ARM. Image: John Gollings

Civic: Parklands Project by Lat27 with AAA Joint Venture and DesignFlow. Image: John Gollings

Civic: Riverside Centre revitalisation by 360 Degrees. Image: John Gollings

Civic: Surf Parade Place Making Project, Broadbeach, by City of Gold Coast. Image: Remco Photography

Parks & Open Space: Scarborough Beach Park Southern Upgrade by Aspect Studios. Image: Supplied

Parks & Open Space: Slacks Tracks by Logan City Council. Image: Supplied

Play Spaces: Goodstart Early Learning Centre Adelaide Street by Greenedge Design Consultants. Image: Greg Thomas

Infrastructure: Bundaberg CBD revitalisation by Archipelago. Image: Archipelago

Tourism: Maravista by Cusp. Image: Milkana Kirova

Urban Design: Smithfield Street Revitalisation by Place Design Group & Gympie Regional Council. Image: Alan Warren

Urban Design: University of QLD St Lucia Campus Master Plan by Urbis. Image: Supplied

Urban Design: Fish Lane by RPS. Image: Peter Sexty

Landscape Planning: Kangaroo Point Urban Renewal Strategy by Urban Renewal Brisbane, Lat27 & BVN. Image: BCC

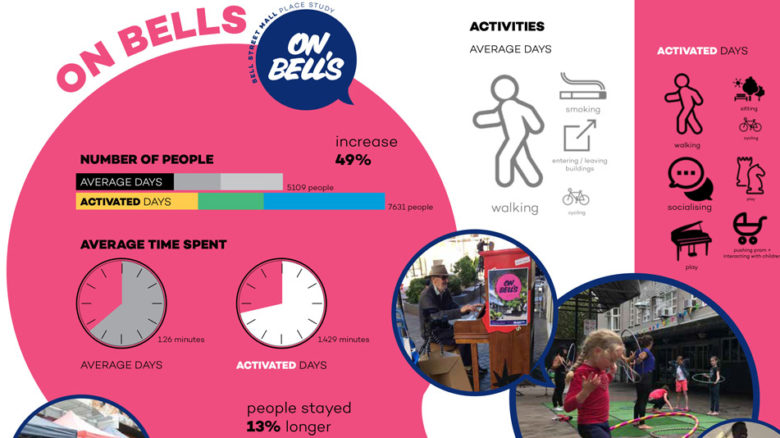

Research, Policy & Communication: Bell Street Mall Study by Tract Consultants. Image: Supplied

Community Contribution: Bell Street Mall Study by Tract Consultants. Image: Supplied

Community Contribution: Palmwoods New Town Square by Sunshine Coast Council and CoDesign Studio. Image: Anita Elliston

Small Projects: Caloundra Christian College Early Learning Centre, by Greenedge Design Consultants. Image: Greg Thomas

Small Projects: The Link by Lat27. Image: Frederick Jones

Gardens: The New Backyard by RPS. Image: Peter Sexty

Regional Achievement Awards:

Scenic Rim: Tamborine Mountain Village Greens by John Mongard Landscape Architects. Image: Troy Rafton

Central QLD: Rockhampton Riverside by Urbis. Image: Florian Groehn

Darling Downs: Oakey Creek Linear Corridor by Fred St. Image: Tessa Leggo

View the full list of award-winning landscape architecture projects from this year’s Queensland Landscape Architecture Awards above.