Remaking Lost Connections: a timely call to rethink the future of the city

In the lead-up to a federal election, and with the state of the environment and climate change identified as major concerns for voters, the Australian Institute of Landscape Architects has launched an ideas competition for Canberra.

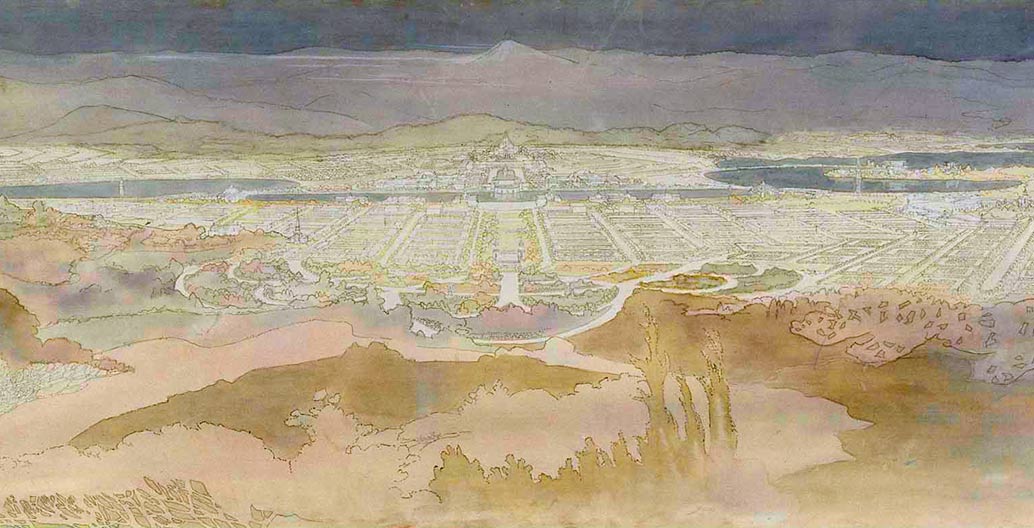

Canberra is a carefully planned city, the outcome of an international design competition won by Walter Burley Griffin – architect and landscape architect – and Marion Mahony Griffin in 1912. Walter Burley Griffin claimed it was “the first time such a thing has been attempted on any large scale”, providing an enviable standard of urban living for its inhabitants within a landscape setting. And yet it “rarely rates highly in the national or international consciousness… little known overseas and little loved within Australia”. A new competition looks to revisit Canberra’s paradoxical fame and disdain, while posing questions about the urgent challenges facing cities today. How can new ideas for an ideal city promote deeper and broader discussion about the local impacts of climate change? Might Canberra’s planned past hold clues to better planning for its future? And what roles will landscape architects play?

The idea for the competition was inspired by a phrase from Paul Keating’s Redfern Address regarding the importance of “psychologically inhabiting this landscape” – in particular, what this might mean at a time when Australia’s landscape is suffering terribly under climate change. While competition registrar Gay Williamson (FAILA) acknowledges that climate change concerns understandably emphasise proving and quantifying the ‘science’, she is keen to point out that the impacts of climate change are also qualitative. “It affects the ‘genus loci’, our relationship to place and our sense of belonging to that place. To make climate change discussions meaningful we also have to start talking about the ‘heart’ and the spirit of our urban landscapes.” Williamson asks, what better place to explore this than the nation’s capital, Canberra?

The competition is entitled ‘Remaking Lost Connections’, but this title is not a call to historicist revival. The announcement of a competition to replace the spire of Notre Dame, destroyed by fire last month, has focused popular attention on the various meanings and aspirations that can surround built form. As Prime Minister Édouard Philippe of France noted, “This is obviously a huge challenge, a historic responsibility.” It is the interpretation and projection of history and of a desired future that is predominantly guiding the many suggestions already being made, albeit not without criticism.

“Remaking is not about ‘re-discovering’ a solution to a problem” explains competition advisor Dr Andrew MacKenzie, but ultimately about “retelling the Canberra story in a way that provokes new learnings, a story from within the heart of the nation’s capital.” That story might come from rediscovering Canberra’s deep geological history and its influence on the way the city has grown. MacKenzie recalls Kate Rigby’s reflection on the complex geology of the Canberra region, its limestone plains and Red Hill’s “story of stone and sky”.

There is also the story of the Griffins, their beliefs around democracy, good citizenship and the social contract between political leadership and the people. What does the capital of a ‘workers paradise’ in modern social democracy look like? MacKenzie wonders, too, what stories need to be told of evolving cultural interpretations of occupation, pointing to Bruce Pascoe’s Dark Emu and Bill Gammage’s The Biggest Estate on Earth as recent works that attempted to make sense of a lost understanding.

There are also many stories latent in the shifting relationship between the city and its biodiversity. “The picturesque, parklike tradition has, over the life of the city, progressively cloaked its complex ecology in a carpet of ‘green’, or more often brown” muses MacKenzie. He believes that recent attempts to remake the landscape have resulted in a biodiverse pastiche. There is a need to better understand the biological legacy of diverse structures, ancient decaying eucalypts and messy herbaceous plants intimately responsive to the unreliable rainfall. For example, Canberra’s two-to-four-hundred-year-old Euclayptus blakelyii and E. melliodora are scattered throughout the suburban landscape. They are perennially at risk of removal, and yet are living lessons for us now, being absolutely suited to challenging shifts in climate.

“Lost could be interpreted as both something that has been misplaced, taken away or not realised” says MacKenzie. “It could even be interpreted as being disorientated and trying to find your way.” For landscape architects and others involved in projects that seek to improve the public realm in particular, the many challenges of compliance, budget and time will resonate as threats of lost opportunities. “It is essentially about what lost opportunities there are in our landscapes and built environments,” he continues, “especially when decisions about the design and management of our landscape are based on ‘risk averse’, ‘cost effective’, the ‘picturesque’.”

The idea of ‘connections’ has the richest potential for exploration, Mackenzie believes. It’s about “parts coming together to make a whole”. The parts may comprise events or moments in time, people or cultures, elements of the landscape, geology, vegetation, water, sky or more. Ultimately, the competition asks how we can remake connections. How can we critically engage with new ways to read, appreciate, respond to and inhabit the Canberra landscape, and, by implication or inspiration, the landscapes of cities elsewhere?

Cities are cultural artefacts as well as built environments. Leading American urban planner Edmund Bacon declared in 1968 that Canberra “is not exclusively an Australian possession, but… is a significant manifestation of the creative upsurge of world culture.” Yet he also approvingly described Canberra’s site-specific response to its immediate setting: “Here is a network of sweeping vistas, vast gulps of fresh air, superbly exciting and dynamic interactions between the peaks of the hills and mountains and the movements of people.” At the scale of the nation, Australia’s parliamentary records have Sir Charles Frederick Adermann, in the same year, claiming that the national capital “is really a micro-expression of the great sweeps of open space which characterise the geography of the continent”.

The design for Canberra, then, does three things of interest to us today. The first remains absolutely desirable for cities: being alert and sensitive to an immediate environment, and incorporating the benefits of the landscape into the urban framework; what we would now call living or green infrastructure. The Australian Institute of Landscape Architects has been advocating vigorously for the benefits of living infrastructure, advising and seeking policy acknowledgement from major parties. The absence of comment and policy from the Coalition Minister for the Environment, Melissa Price, has not gone unnoticed. Yesterday, Labor announced a Plan for Cities. This outlined a Living Cities Strategy committed to “recognising the need to change the way our cities work to keep our cities liveable” via a raft of specific policies including a Green Infrastructure Plan.

The second aim common to many cities today is to offer an ideal of internationally appreciated urban quality. At one level, this is about global competition for talent and business investment. At another, it is about manifesting globally recognised values and continuing the long human project of realising space for a good life. Griffin was explicit: “I have planned a city not like any other city in the world. I have planned it not in a way that I expected any governmental authorities in the world would accept. I have planned an ideal city – a city that meets my ideal of the city of the future.”

Even more than this, in the Anthropocene, the planet itself becomes something we must be responsible for shaping and reshaping, so how we model our cities necessarily reflects an understanding of global impact and care. It is no longer possible to do no harm by being hands-off, let alone be a good city by moving waste, poverty or other problems somewhere else (significantly, the Griffins were responsible for the design of lowly urban infrastructures such as incinerators, as much as more exalted cultural institutions).

The third achievement of Canberra – the one for which it was explicitly created – is as a national capital. But perhaps this was a lesser concern for the American Griffins, who went on to look at exemplary design for India, excited again by intercultural opportunity, novel site specificity and universal principles, including interests in “preservation of habitat and wildlife”. This is again attuned to current concerns as resurgent nationalism poses protectionist policies in response to the borderless problems of climate change and the pursuit of universal human rights in a global era.

The big questions of the competition are clearly a concern for more than landscape architects. For Williamson, the enthusiasm of the Commonwealth and ACT Government partners underwriting the competition – the National Capital Authority, the Environment Planning and Sustainable Development Directorate and the City Renewal Authority – is a sign of the significance of the issues to be explored. “The commitment of these agencies to sponsoring a dialogue that goes beyond the prosaic, to develop a better understanding of the intrinsic, perhaps intangible value of the urban landscape, is laudable” she notes.

But it is also a very timely, focused and useful opportunity to project a future, to examine and grapple with the overwhelming evidence of landscape systems on the brink of collapse. A swathe of recent media coverage has alerted us to the seriousness of active and immanent climate change impacts. An ideas competition focused on rethinking the development of this iconic, designed urban landscape is exactly what is needed, not just to “ramp up the public dialogue on how Canberra can confront the seemingly intractable environmental and social impacts of climate change [and] inspire new paradigms about the role of the urban landscape in Canberra”, but perhaps also for how the world’s cities might do the same.

_

Registrations are open now and close 20 May.

See HERE for more information on the competition and entry requirements.