Prepping a Victorian playground for a bear hunt

Jeavons Landscape Architects’ award-winning sensory courtyard fulfils a hefty brief. Part-playground, part-outdoor classroom, it pulls together myriad elements to help get intellectually disabled students in touch with their senses.

There are many overused words in Standard Australian English. “Sensational” is one word which has diverged far beyond its original meaning – it’s more likely to be used as a positive affirmation than for telling someone their “sensational” description is rather, well, sensational. In the real estate world, the word “sensory” is liberally sprinkled about, from “sensory” bathroom fixtures to the “sensory” in-house cafes found in display suites. And, of course, Melbourne gave us a short-lived sensory shopping experience, complete with its own scent.

A new playground in Cranbourne, Victoria, lays claim to this “sensory experience”, too – but, in this instance, the landscape architects responsible took their conception of “sensory” back to fundamentals.

“In this context, the way we interpreted ‘sensory’ was informed by the client – a literal way of viewing what it meant,” says Felicity Brown, senior landscape architect at Jeavons Landscape Architects.

A pupil makes the most of the hand-operated water pump.

Small Projects Landscape Architecture Award: Marnebek Sensory Courtyard (Jeavons Landscape Architects).

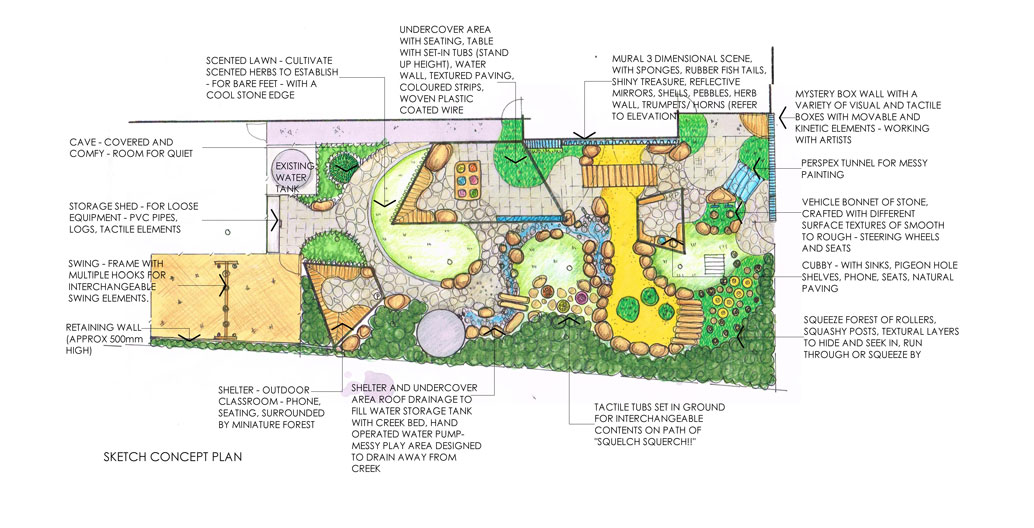

The final site plan.

Looking into one-half of the courtyard, with the sensory forest in the background.

Versatile outdoor desk space.

The playground was designed for the Marnebek School, a school for students with “mild, moderate and profound” intellectual disabilities. This playground, unlike other schools’, is designed with the curriculum in mind. The project works in conjunction with the school’s existing “sensory room” to help students build awareness of their own senses and control their responses to stimuli. There are spaces for outdoor learning, while many of the elements of the playground are used in conjunction with the school’s occupational therapists.

“Children with a wide range of senses to process are the beneficiaries of this project,” Brown says. “They range from children who are oversensitive and under-sensitive, and a huge gamut of abilities in-between.”

In a traditional school playground, the elements for “play” are overtly programmed. Slides, rope bridges, see-saws, among other things, are codified as “play spaces”, with the expectation that pupils (or playground users) will cognitively follow-suit. But not all children possess the same cognitive abilities at the same age.

“With Marnebek, you’ve got children that will just curl up in a corner, children who will want to run all over it, and some children who will take possession of certain elements,” she says. “This playground helps them to extend themselves to see more opportunities for investigation, including assessing risk.”

Over recent years, calls for play-spaces that allow children more opportunity to take risks have been increasing, but in this project risk is an especially delicate consideration.

“There are children who have difficulty processing just how far they can extend themselves, because the whole concept of ‘play’ that we can take for granted is a totally different story for them,” she says. “While other schools might share similar ‘play’ elements as Marnebek, we need to provide that extra layer of care for kids with differing abilities.”

A lush green pathway. Image: Mary Jeavons.

A pupil gets chatty via talkies.

The sensory forest with a series of tactile poles to run or push through.

A pupil bursts through the courtyard's colourful perspex walls.

The courtyard's perspex tunnel, primed for budding painters.

The live musical element of the courtyard: A sound installation by HAPI (Herbert Jercher).

A child getting into some sea-themed play.

To help kids get in touch with their senses, one approach the playground takes is an onomatopoeic exploration of senses. Inside the playground, you’ll find a “squeeze” forest, a collection of squashy posts and rollers that children run, or squeeze, through. There are paths that have set-in tubs, creating a journey you can either “squelch” or “squeerch” through.

If all of this sounds like it’s the perfect accompaniment to an equally onomatopoeic picture book, then you’d be right. Two books informed the final design: Alison Lester’s Imagine and Michael Rosen and Helen Oxenbury’s We’re Going On a Bear Hunt. Given the latter, it shouldn’t be a surprise to find the garden harbouring a “bear cave”, nor, given the former, a 3D underwater sea mural.

Both of these books revolve around the idea of real-time journeys coupled with tangential adventures. In turn, Brown made a deliberate choice to give the playground multiple journey-points to mirror these texts’ “innocent perspective of viewing the world.”

“We liked the idea of the journey that We’re Going On a Bear Hunt encourages. You can ‘go under, over, or through’ things, which children can do throughout the playground,” she says. “We wanted to relax the space so children could be consumed by their imagination without feeling as though they were constantly in therapy.”

And that’s the curious trick that Brown and her team has pulled off: a space that is equally regenerative and sensitive, while not forgetting to be fun.

—

Jeavons Landscape Architects are the 2017 winners of the Victorian Australian Institute of Landscape Architects’ Small Projects Landscape Architecture Award.

AILA Victorian Landscape Architecture Awards winners 2017

Parks and Open Space Award of Excellence: Wooten Road Reserve Interpretation Space (GLAS).

Infrastructure Landscape Architecture Award: Jock Marshall Nature Reserve Walk. (Urban initiatives).

Community Contribution Landscape Architecture Award: The Journey Interactive Map (Tract).

Infrastructure Award of Excellence: Rememberance Drive Interchange (OCULUS, VicRoads, & Paul Thompson).

Play Spaces Landscape Architecture Award: Valley Reserve SPARC (Playce).

Gardens Award of Excellence: NGV Grollo Equiset Garden (OCULUS).

Play Spaces Landscape Architecture Award: Rosebud Foreshore (HASSELL).

Landscape Planning Landscape Architecture Award: University Square Master Plan (City of Melbourne, City Design Studio).

Urban Design Award of Excellence: Hawthorn Arts Centre Civic Space (Site Office).

Land Management Award of Excellence: Armstrong Creek (GbLA).

Research, Policy and Communication Award of Excellence: Landscape Architecture and Environmental Sustainability (Joshua Zeunert).

The Marnebek Sensory Courtyard is one of several exceptional landscape architecture projects to win an at this year’s Victorian Landscape Architecture Awards. View the full list of winning projects from Victoria’s 2017 entries above.

Foreground has published state-by-state coverage of the Australian Institute of Landscape Architects’ 2017 Landscape Architecture regional awards. View them here.