Paved for the people: In Melbourne, a parking lot has become a public square

“They paved paradise and put up a parking lot,” sings Joni Mitchell. But at Prahran Square, almost the reverse took place. Lyons Architecture and Aspect Studios have transformed a carpark into an urban sanctuary of sorts, an island of open space and amenity in Melbourne’s rapidly densifying suburbs.

Prahran Square addresses a desperate need to provide safe space for a growing local community. Located in a suburb just south-east of Melbourne, the new 10,000 square metre public space occupies a once unremarkable asphalt carpark. Hidden behind a row of shops fronting busy Chapel Street, it was used as a general back-door thoroughfare, and with a vibrant nightclub scene nearby, also became part of a well-known drug and party scene by default. For over a decade Stonnington council resisted pressures to sell or commercialise the space, instead raising $65 million to invest in a public facility that would service a wide spectrum of community needs.

Architect Adrian Stanic, director at Lyons and lead of the square’s design team, is actually a local himself and applauds the efforts of council to ensure that the public was gifted with this key space. Stanic knows as well as anyone the many roles Prahran Square was called on to play, while also understanding that it would be something new for locals.

Over time, plantings will turn this space into a leafy shelter from Australia's at times baking sun. Photo: John Gollings

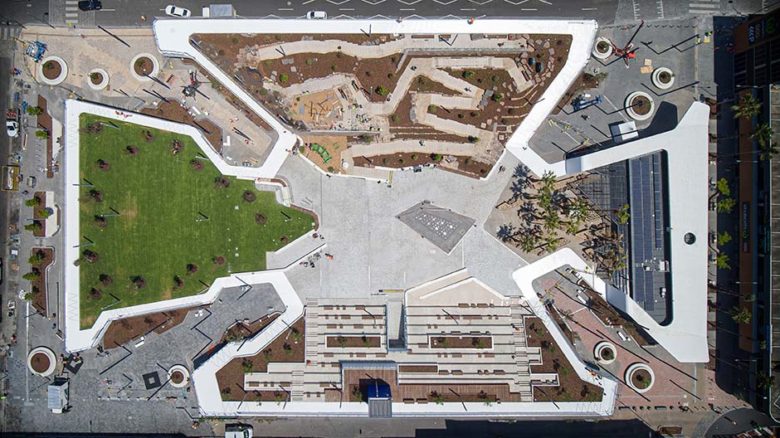

Prahran Square seen from above. Photo: John Gollings

A smoking ceremony was held at the opening of the square, which sits on the lands of the Woiwurrung and Boonwurrung tribes of the Kulin Nation.

“This was a very strange space because it was really the realm of cars, and being the realm of cars, it was always quite uninviting for the pedestrian,” says Stanic. “Sunday morning you’d find all these doughnut patterns on the ground,” he adds, recalling the site’s previous typical use on a Saturday night, when cars would come into the empty carpark and do burnouts.

“It’s changing rapidly,” says Stanic. “And I guess the council are also feeling like residents are going to drive change in the way that the street is used and the way public space will be used.” Prahran has very little public open space and has not had that sort of quiet space Stanic thinks is vital for locals – a large, open area to take the kids and meet people, without necessarily having to shop. The square is a new kind of purposeful space for Prahran.

A form that grew from its context

While it is new, the square has deliberately linked itself to existing public spaces: Princes Park to the east, Grattan Park to the west, and surrounding pocket parks and streetscape. “Yes, it’s a big object in a way, but it is very tied in to all these other local destinations and to the street and the local scene,” says Landscape architect and director at Aspect Studios, Kirsten Bauer. The bluestone of the Town Hall comes in from the south and red brick of the market from the north. Vegetation too references wider context. The palms and Victorian Gardenesque flower beds in the square’s north link to those in Grattan and Princes Gardens. And then there is Greville Street in the south where aspects of the work of Rush Wright Associates has been brought to the square.

As Bauer, explains the form and shapes of the project came about in multiple ways. Firstly, there was a lot of strategic work and conversations about Prahran. Diagrams from their winning submission to council show how the design team worked through connections to the neighbourhood’s historical aspects.

“We picked all the landmark features and were interested in the way – before phones, before smartphones and before maps – people would navigate by visible landmarks,” explain Stanic. People rarely do it today, he says, because they are looking down at devices instead. “So we thought perhaps that some sort of residual idea of those landmarks – even if it’s a highly abstract – was a nice way of kind of embodying some of the history into the site.”

In these ways, the square is part of a greater public realm strategy that includes surrounding street, public forecourts and pocket parks to create a new integrated precinct. “All the streets started to become shared, and with Prahran Square, we started to create a civic village, which is a combination of squares, parks, streets,” says Bauer. “That was always the bigger idea, defining little projects that all slowly start to weave together.”

Weaving was an early concept. It references the old textile industry in Prahran, particularly around the drapery sector of Greville Street. The rear of the multi-storey department store overlooking the site, for example, includes prominent text advertising the drapery department that was once inside. For Stanic, the weave idea helped define spaces for activities. For Bauer, how you would use Prahran Square is obvious. “It’s a unique form but in many ways it is a classic square with programmes around the edges,” she says. Each edge has its own material and use – lawn for sitting and lolling about, forest-park to meander, amphitheatre seating terrace, and palm-shaded ornamental garden beds with cafe. “They’re classic landscape programs really.”

Each of these sides, however, faces in towards the central square. This was good for drawing attention to whatever was happening in the square, but it also meant that the corners and diagonal thoroughfare across the square would need attention to make the links to surrounding streets clear too. Wide openings at the corners draw the gaze and the body into and through the square. But then there are layers below the square. “We looked at flipping the edges up to reveal and bring light into the car park below,” Stanic says. The raised edges let light in, but also allow the eye to connect the ground space with the internal sunken parking.

In such a big space, the design team and Council were conscious of having enough "park elements" – such as playgrounds. Photo: John Gollings.

Prahan Square is now usable public space, rather than a public carpark. Photo: John Gollings.

A sweeping wall was a byproduct of the car ramps but offered an opportunity for playgrounds at the top and bottom of the park. Photo: John Gollings.

Lines of safety

Good visibility for passive surveillance and therefore better safety is a well-known public space requirement. The many-layered weaving, lifting and folding-back gestures of Prahran Square have resulted in an overall composition that includes varied and nuanced spaces. Both Stanic and Bauer speak of a graphic and conceptual ribbon, tying, stitching and weaving the up-and-down, in-and-out of the square. It is easy to point out a white line tracing and dipping around the boundary of the square in aerial photographs, but the ribbon is less persuasive on site. The ribbon concept has already done its job, having helped to organise a clear and layered suite of programs and views.

A more practical incentive and form-driver can be understood to have evolved from a Crime Prevention Through Environmental Design (CPTED) analysis, to ensure there were safe sightlines through the square. Council is well aware of the issues around Prahran of homelessness, drugs and especially graffiti. The graffitti challenge led to concrete being painted grey so it could be easily repainted. There is full CCTV surveillance and security staff are considered part of a necessary ongoing investment. Stanic recalls walking through one night when kids were causing a bit of trouble. “The interesting thing is that anything happening in Prahan Square is immediately obvious. You can really get the sense of something going on. You’re in a big public space and everything is very visible.”

A lot of work was also done to restrict cars and manage traffic on surrounding streets. Council was sensitive to not “go crazy with crash barriers” says Bauer. Bollards were limited, with minor grade changes and tree planters preferred to restrict vehicle access, especially at the visually open corners of the site. Other public space in Prahran is less well monitored and feels less safe, but for Bauer, improving this prominent public space helps the rest too. “It’s really about the whole precinct being activated and made to feel safer.”

Familiar joys in a unique space

Once decisions were reached about where each type of activity would go, there was more work to determine the furniture and other details. Some decisions were to do with the unusual scale. Such a big space “needed some ‘park’ elements” believes Bauer, as it may otherwise just seem to be a space waiting for events to happen. A zig-zag ‘forest’ walk and playgrounds, sloped lawn, art and flowering garden-beds all triggered familiar activities for local residents to enjoy. Each corner of the square too has a different materiality, a different character and different things to see and do.

In a way, the designers needed to imagine a future community for the square, even while drawing on the Prahran they already knew. “It’s not like a building where you have immediate curated occupancy of population,” Bauer explains. The square would develop new relationships with the community as its planting and events and uses evolved, just as the community would develop its relationship with the square. Bauer uses the seating as an example of fostering some of those specific relationships. “It’s like saying, we’ll develop a relationship with the lunch person and give them seating for that, we’ll develop a relationship with mothers and kids and give them something special to sit on, we’ll set up a relationship with the students with laptops with this type of seat, and so on.” For Bauer, it is like designing for personalities and giving the seats personalities to suit.

Bauer believes the square has turned out to be “very Prahranny!” It’s very eclectic, it has something for old and new communities, passing populations of young people, different national backgrounds, night spots, market-going families, the fashion people, elderly and infirm people, people watching, meeting up, just hanging out. “When we knew this square was going to be such a new and different thing for this community, we thought it was good to give little signals about what you might do there: here’s a lawn to lay on, a bug to sit on, a place you can have events and watch, a garden to sit in and smell, a forest to wander through…It’s joyful!”

Prahan Square construction. Photo: Aspect Studios

Prahan Square construction. Photo: Aspect Studios

Prahan Square construction. Photo: Aspect Studios

Construction complexity

Such layering and weaving requires many hands and is another reason why the project has been so collaborative. Along with Lyons and Aspect Studios, the team included artists Paul Carter and Bruce Ramus. “We put the challenge down to both of them because we originally had them both working in slightly different directions,” said Stanic. He says they were excited when it was suggested they work together “So it was a very serious collaboration, for both of them.” The deep blue pipes brought life to the corners of the square. “It was just a beautiful abstract work that populates the corners with sound and imagery, making each one an entry or gateway into the square.”

Even the usual liaison with engineers was increased by the complexity of the square’s shaping and layering. Aspect was intimately involved in developing the structural documentation – “two or three different times” recalls Bauer – to ensure planting space and technical compliance for the sloping forest landscape. Stanic describes the team’s efforts to work out how car park ramps could come in under the structure. Part of the reason there are some high parts in the forest is because of the main car park entry sweeping under it and that led to the opportunity to create a wall and playgrounds at the bottom and top.

Despite what seems like a generous size and number of plants, both Bauer and Stanic are keen to explain that the planting needs to grow. They believe it looks “pretty raw” at present when the public expect leafy shade. A good canopy is coming for the future, but plants that could create instant canopy now would not have survived. “We didn’t want to put in something that looks good for a year and then doesn’t grow,” Bauer says. Yet they are hardly typical or boring choices, mixing the texture and fragrance of Australian natives and species of Mediterranean townscape pots.

Complexity can foster fun. Bauer had wondered how they could possibly tell a story about habitat or ecology in such a tightly constrained environment. They created different types of animals based on insects from the real environment, “but really we just wanted kids to wonder what the weird bug is!” she admits. “It’s a bit magical, cheeky and whimsical, a bit like grottoes are and as strange as a forest in an urban public space is!”

The team also worked closely with council’s horticulturalists to finalise species and have their own nurseries procure or prepare plants. Through the process they have brought on specialist horticulturalists and a square manager in an ongoing role. “Like any big area you need a place manager and they will be developing that role,” says Bauer. She is adamant that this sort of advice and management is what landscape architects need to be better known for. It’s vital for a project’s success and to a process of developing and sharing knowledge. “We don’t want to just walk away when a project is built. It’s certainly not finished.”

A project for the future

Prahran Square showcases the vital importance of public space. Specifically, it is an argument for the value – however hard to capture – of uncommercialized, freely accessible, high-quality and richly resourced local space. And while it has a generous car park and can host small and very large events, for Stanic it is mainly about having and promoting a place to hang out. “It’s always about people and it’s about what people can do in the square, their various experiences,” he says. “You come into the square, you’re immersed in the square. This is the square, you’re here.”

Stonnington council have delivered the most ambitious public realm project in Melbourne for many years and, as Bauer emphasises, they did it as a local council, not a capital city. It’s not a project about appeasing the community because there is a shortage of public open space, although there certainly is. It is a project about where the community is going and where they want to go, and how they want to change and grow to get there. This is not a public space of nice trees and seats but is taking bigger risks. And Bauer warns “bits of it might well fail, because you can’t ensure against that.”

Square, amphitheatre, carpark, lawn, playground, thoroughfare, streetscape… this unique hybrid type has delivered a unique and fun hybrid form. “It’s a project for the future,” says Stanic.

–

Dr Jo Russell-Clarke is a registered landscape architect and Fellow of the AILA. She is Foreground’s Editor-at-Large and a senior lecturer at the University of Adelaide. Her research interests include histories of the suburbs, the changing faces of food production, consumption and tourism and their landscape impacts, and new concepts of the commons as public landscape infrastructure.