Picturing paradise: Marion Mahony Griffin and Castlecrag

In 2021, Castlecrag, one of Australia’s most enduring ‘model suburbs’, celebrates its centenary. Dr Anne Watson reflects on the remarkable vision and talent of one half of the design team behind the project—Marion Mahony Griffin.

Autumn 1924. The first seven houses have been built at Castlecrag and the harbourside estate’s system of contoured roads and generous public reserves is taking shape. Architect Marion Mahony Griffin is dividing her time between Melbourne—where Marion and husband Walter Burley Griffin’s extraordinary Capitol Theatre is nearing completion—and Castlecrag, the suburb the Griffins initiated three years earlier. In May 1924 Marion writes to her friend, the renowned Australian author Miles Franklin: “It’s enough to make one’s hair stand on end how determined the authorities are that nothing beautiful shall be left in Sydney or anywhere else in this beautiful country.”

Over a decade earlier Franklin had visited the Griffins in Chicago soon after they won the competition to design Canberra in early 1912. Reporting on the meeting for Sydney’s Daily Telegraph in July that year Franklin and co-author Alice Henry were among the few writers to acknowledge Marion’s significant role in the preparation of the Canberra plans:

Mrs Griffin is also an architect, and is closely associated with her husband in his work. As they show their visitors designs of other undertakings upon which they have collaborated it is plainly apparent their ideals are happily interwoven.

Franklin describes Marion as “slender and dark, with luminous brown eyes … a lady of charming personality and nimble wit.” The pair were clearly kindred spirits and became regular correspondents. When Marion wrote of her frustration over Sydney’s unsympathetic development a decade later, Franklin was no doubt receptive. Castlecrag, where architecture, landscape and community were intended to co-exist harmoniously, was to be the Griffins’ ‘model residential suburb’, an antidote to the spreading obliteration of Sydney’s natural beauty.

Marion Lucy Mahony was born in Chicago on 14 February 1871 and grew up in a stimulating environment where social issues were discussed and outdoor activities encouraged. At a time when few women pursued tertiary education, let alone a male-dominated profession, she graduated in architecture from the Massachusetts Institute of Technology in 1894. Marion was the second female architecture graduate at MIT and became the first licensed female architect in Illinois. She worked in Frank Lloyd Wright’s Chicago office from 1895 to 1909, a period coinciding with Wright’s most intensely creative and productive years and the consolidation of the ‘Prairie School’ style on which his international fame would be built.

Marion was a skilled designer and a gifted artist. In Wright’s office she designed furniture, lighting, stained glass and decorative fittings, but it was for her elegant Japanese-inspired presentation drawings that she was particularly valued. When Wright abandoned his practice and family to travel to Europe with the wife of a client in late 1909 Marion independently took on several of Wright’s unexecuted projects. For the most substantial of these—the design of the residential enclave, Millikin Place, in Decatur, Illinois—Marion turned to Walter Burley Griffin, a former Wright employee (1901-06), to design the landscape scheme. The project launched Marion and Walter’s professional partnership and cemented their personal relationship. In the Chicago summer of 1910 Marion added her monogram to her first known presentation drawing for Griffin. The FP Marshall house rendering—showing perspective, site plan and interior cross-section framed by decorative foliage—would establish the unique presentation format for their subsequent collaborative American projects including many houses and, most notably, the Rock Crest/Rock Glen development in Mason City, Iowa (1912).

United by their shared ideals—architectural, environmental, social—Marion and Walter married in June 1911 and in May 1914 relocated to Australia. Based in Melbourne, then the site of the Federal Capital Office, the Griffins’ practice was a busy one as commissions for many significant projects rolled in. The Café Australia (1916), Newman College (1915-18), Capitol House and the Capitol Theatre (1921-24), numerous residences as well as planning of the Ranelagh and Glenard estates on Melbourne’s metropolitan fringe, dictated a hectic work schedule that Marion relished: “The only thing I take any interest in doing is the work and I keep at it long after I have a curl in my back bone, and am sick with fatigue.”

Nature and architecture were Marion’s twin passions. An intrepid bushwalker, she was captivated by the Australian landscape and became highly knowledgeable about its unique native flora. It was a natural step for her to translate her passion into artworks: “I felt that the Archangel who painted Australia was the greatest of them all. Everything is so decorative … You don’t have to be an artist there, the picture presents itself to you in perfection.”

The series of ‘Forest Portraits’ dating from 1919—evocative, poetic studies of native trees executed in watercolour on silk or ink on linen—are a truly unique legacy of Marion’s Australian sojourn.

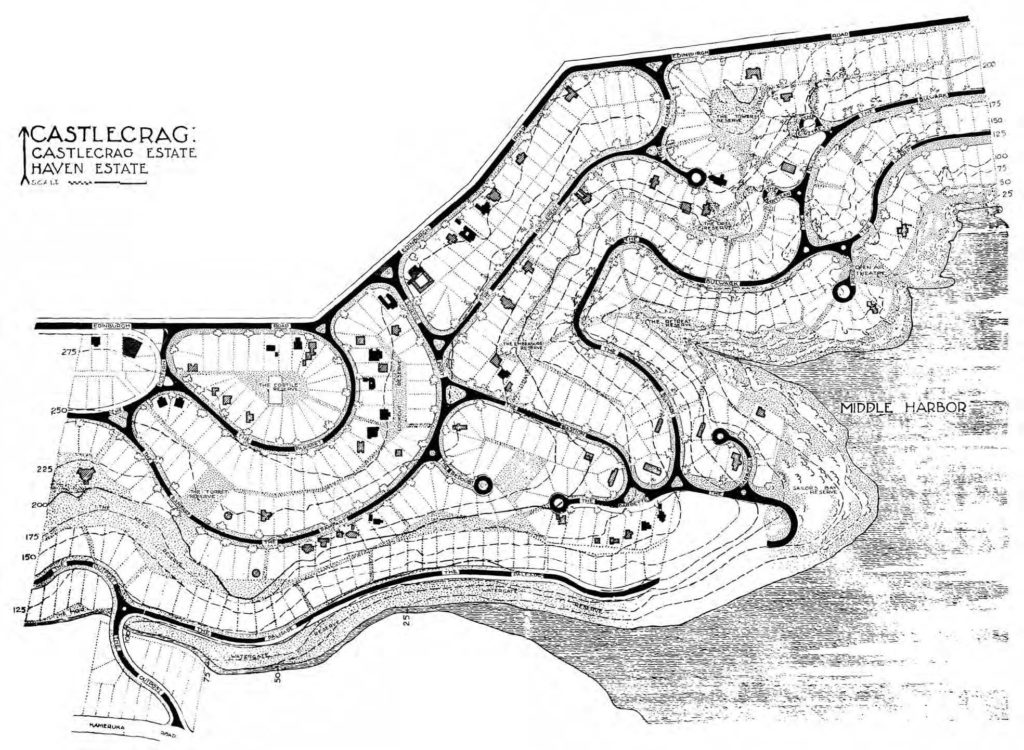

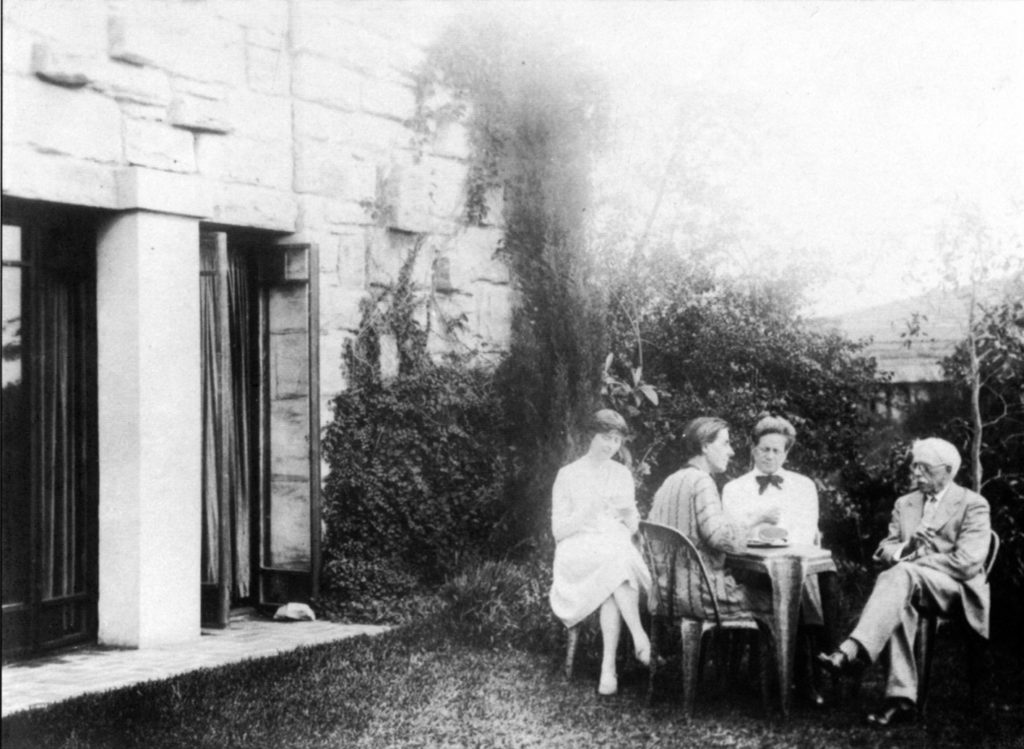

In 1920 the Griffins’ greatest Australian adventure began when, with a group of shareholders, they acquired a large tract of land on the shores of Middle Harbour. Castlecrag was to be the their answer to Sydney’s rampant development, an ideal suburb of houses, reserves, walkways and contoured roads “aesthetically in keeping with the surroundings, so far as possible of the native rock and subordinate to the natural beauty of the land.” The Griffins lived in Castlecrag from 1925 to 1935, Marion becoming deeply involved in the community’s life, most memorably the plays staged in the open-air Haven Scenic Theatre constructed by residents in the early 1930s. The Haven remains today, as do 14 Griffin houses built before the Depression and other factors ended the Griffins’ utopian aspirations. The beauty of Castlecrag’s surviving natural amenity is testament to the timelessness of the visionary ideas that anchored the Griffins’ grand suburban venture.

In May 1936 Marion joined Walter in India to work on new commissions, but the excitement of a re-energised practice in an exotic country was short-lived: in early 1937 Walter died suddenly from peritonitis following an operation. Grief stricken, Marion returned to Sydney and in October 1938 departed Castlecrag, her beloved “bit of Paradise on Earth”, and returned to Chicago. Her last great work before her death in 1961 was her unpublished magnum opus The Magic of America, a 1500-page assemblage of transcribed documents, photographs and commentary recording her and Walter’s lives, separately and together. Exploring its many layers, now possible through digitisation, is a compelling journey into the long life and complex intelligence of one of the 20th century’s most original women.

To celebrate Marion Mahony’s sesquicentenary and the centenary of the Griffins’ Castlecrag, on 14 Feburary 2021 guest speaker Dr Anne Watson will give a talk at the Museum of Sydney entitled ‘What made Marion’s Hair Stand on End?’ An exploration of Marion Mahony Griffin’s pioneering role as an environmentalist and urban planning advocate in Australia through her art, architecture and writing.

Tickets $30 and include free entry to the museum and Paradise on Earth exhibition. Bookings essential as seats at half capacity for covid social distancing: https://www.trybooking.com/BNFTF

Dr Anne Watson has had a long association with the Griffins including as curator/editor of the 1998 Powerhouse Museum exhibition/catalogue Beyond Architecture: Marion Mahony and Walter Burley Griffin in America, Australia and India, editor of Visionaries in Suburbia: Griffin Houses in the Sydney Landscape (2015) and curator of Paradise on Earth (Museum of Sydney, November 2020-April 2021) celebrating the sesquicentenary of Marion’s birth.

This essay was originally published as ‘From Chicago to Castlecrag’ in the Walter Burley Griffin Society’s newsletter and is republished here with its permission.