On the outskirts of Brisbane, an urban drain takes on a life of its own

Landscapology and Bligh Tanner have cut a waterway free from its concrete constraints to create living, breathing hydrological infrastructure, for humans and non-humans alike.

In certain parts, Ipswich’s Small Creek takes the serpentine form of a waterway that has been slowly unspooling for centuries. For a roughly one-kilometre stretch before it meets the larger Deebing Creek, Small Creek follows a wandering line through a series of meanders, riffles and pools that wouldn’t look out of place in a national park, rather than wending past an industrial estate on the edge of metropolitan Brisbane.

The setting is a strong clue to the origins of this seemingly organic geomorphology, which in some ways is a manmade construct just as purposefully functional as the warehouses and factories alongside it. Track the creek east, away from the confluence with Deebing Creek, and you’ll meet Briggs Road, which it trickles under. Beyond this point, the creek’s coils become a linear concrete channel—the form that its entire length was held to for the four decades before its lower reaches were ‘naturalised’.

In 2016, City of Ipswich council appointed landscape architects Landscapology and engineers Bligh Tanner to help them return 1.6km of what was effectively a drain to a living waterway. Bligh Tanner’s Alan Hoban describes the pre-existing grey infrastructure as a monofunctional “1970s special” but the hope was it would become home to native vegetation and wildlife not seen since colonists cleared the area for grazing. Locals, in turn, could enjoy this renewed ecology as parkland. The main driver behind the project, though, was water quality, with much of the funding for its development coming from a government stormwater offsets scheme.

Students from a nearby school walk Small Creek's old concrete channel. Image: Courtesy Amalie Wright

Aerial shot of Small Creek, circa 1946. Image: Ipswich Council

Small Creek’s catchment is intensely developed; its water flows from areas of both light industry and housing, where it accumulates hydrocarbons, heavy metals and other nasties. After merging with Deebing Creek, these waters feed into the Bremmer River, and from there the Brisbane River and eventually Moreton Bay—a marine environment worth $7.56 billion a year to the South East Queensland economy that is slowly being killed by mud and poison from the polluted waterways draining into it.

“What was previously on site was a fairly conventional concrete channel, like something you’d see in almost any part of Australia. It provided a drainage function—probably good for flood conveyance, and not much else,” says Hoban. “In many ways, the concrete drain is a product of old engineering thinking and the new waterway is a product of an emerging progressive engineering approach, which is environmental engineering.”

We could see the renewed creek as part of what some are calling a burgeoning hydrological renaissance. Recent changes in both the culture and technology of water management allow designers to apply a much more sophisticated understanding of the forces at play in water infrastructure than in the past. Hydrology now encompasses diverse questions around ecology, landform, economics, and people—which has brought the potential ‘downstream’ impacts of working with water, in both a literal and abstract sense, to the fore.

In a dynamic system, monofunctional efficiency can bring unintended consequences. As Hoban points out, a concrete drain for one often creates just as many problems as it solves. “It moves water away really quickly, but that causes flooding issues downstream. It causes water quality issues downstream that someone has to manage. And then you have all those issues of losing those places of delight and wildness within an urban area.”

One way to address those downstream issues of flooding and poor water quality is by slowing the water down and holding it in the landscape for longer. This makes fast-moving, erosive flows less likely, but it also allows time for both manmade and natural systems to metabolise pollutants. To that end, the new creek is 60% longer than the previous drain, thanks to those looping, seemingly natural meanders and pools, which in turn make it possible for reeds and other plants to take root and help filter the water.

The first two of the project’s four stages of development recently received an Award of Excellence for Land Management at the 2020 Queensland Australian Institute of Architects Awards, with the jury describing it as setting a precedent for all future creek naturalisation works. It’s not without precedent itself, with both Amalie Wright of Landscapology and Hoban pointing to Clear Paddock Creek in New South Wales as a touchstone. Much like Small Creek, that project replaced 750 metres of an old concrete-lined stormwater channel with a “naturally functioning but manufactured” creek system that captures run-off and reduces pollution. It was completed roughly two decades ago, though, and while there have been a number of projects around the country since then that follow similar principles, very few if any of them could be said to approach the scale of Clear Paddock Creek, let alone Small Creek.

While the scale of the transformation at Small Creek is impressive, and significant in terms of its impact on the environment, it’s the project’s ambition to challenge not just the monofunctional engineering paradigm, but also the cultural assumptions that paradigm rests upon that sets it apart.

Fear of flooding, of pests and of disease drove much of the concreting and channelling of Australia’s urban waterways over the past two centuries. Not without reason, as waterways do flood and do attract wildlife, some forms of which can be more desirable than others, especially in Australia. For much of Australia’s history, urban waterways have also been used as drains and sewers. The reigning assumption on the part of the professionals and politicians responsible for managing urban waterways was that those fears were the predominant concerns of the communities they served, and that the best way to address them was through grey infrastructure.

The team behind Small Creek’s transformation didn’t make those assumptions. Instead, they went out and asked the people living, using and looking after it, what they thought of replacing the drain, and what they might like to see there in its stead.

“We wanted to approach it with that open community engagement upfront—the team took it to council at the beginning,” says Wright. “It’s risky for council to do this, especially given the things the community is likely to be concerned about are big things to be concerned about.”

Part of that community engagement took place during a ‘design your creek week’ when the team pitched up on site to talk through the options with the local community. This included students from the nearby Bremmer High School (who, in an organic adaptation of otherwise monofunctional infrastructure to multi-functional ends, had taken to using the concrete drain as a cycleway and shortcut to school), local residents, the council’s maintenance team, local fishermen and a birdwatching group.

As Wright describes it, the experience revealed a sophisticated understanding of the wildlife that even the straitened amenity of the concrete drain supported, and a strong desire for more of it. Importantly, though, it showed that the community might in fact be comfortable with one of the new creek’s most radical departures from orthodox grey infrastructure—it’s capacity to shrink and contract, shift course and change shape.

“One thing we wanted to do in Small Creek was set the creek free—erosion and deposition are natural processes, so we wanted to enable those,” says Hoban. “There are some areas where we do use rock or concrete to protect infrastructure, but there are other areas where we deliberately don’t provide any armouring and have set it up so the creek has the ability to meander and evolve over time.”

To help explore potential options for how the new creek might develop, the team brought in a specialist “creek doctor”, in Hoban’s words—fluvial geomorphologist Geoff Vietz.

“During the co-design process with community, we were able to set up our computers running complex flood models out in the field. We were able to talk the community through how flood modelling works, and show them the results,” says Hoban. “We could show them how changing the design of the creek’s vegetation or earthworks could change the outcome. It helped build a lot of trust around flooding.”

Some of the outcomes of that very public experimental modelling would give a PR flack palpitations, with certain scenarios leaving residents’ houses partially submerged. Wright, though, says the residents took it in their stride, as it demonstrated that the project team were alert to the risks and that, at the very least, they would ensure the design wouldn’t be any worse for flood management than the concrete drain.

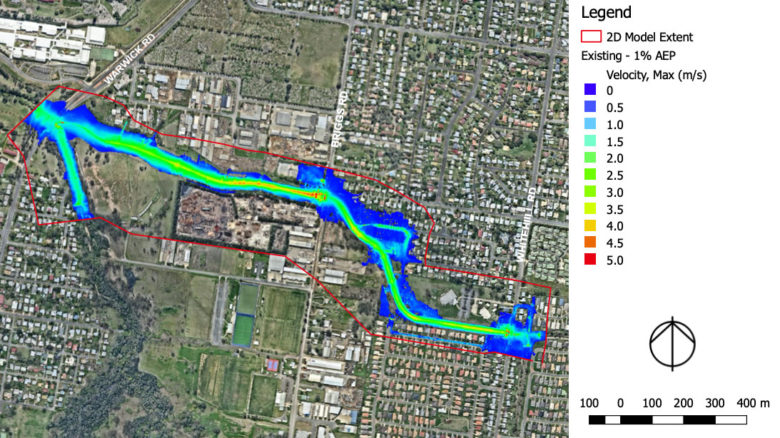

Flood model for the old creek. Image: Courtesy Amalie Wright

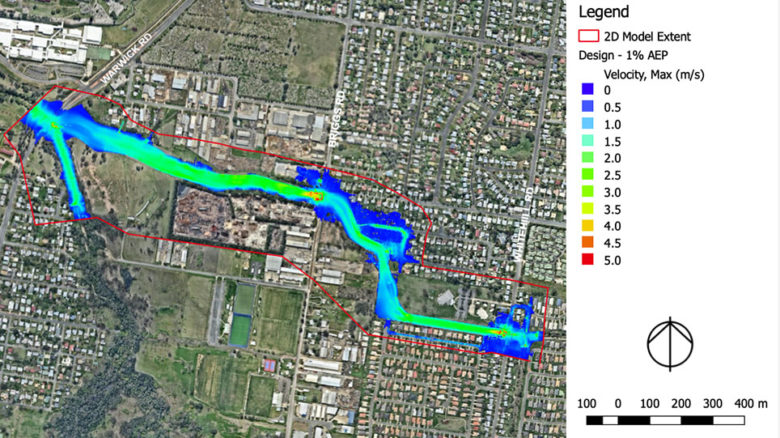

Flood model for the new creek, as designed. Image: Courtesy Amalie Wright

Wherever the creek gets close to property boundaries, there is underground rock armouring – the equivalent of groynes. Much of the armouring in the site is concrete from the old drain, which has all been recycled on site. “We were keen right from the start to try and reuse the existing drain concrete, and I think we brought a different level of thinking to that,” says Wright.

Where the creek runs under Briggs Road, council has installed a concrete culvert. In response, the naturalisation project becomes less ‘concrete-y’ as it moves west away from the culvert. The old drain was left in place and fractured, to let plants take hold. Then the concrete was removed, cut up into slabs, and repositioned to line the channel and create low retaining walls. Further away still, it only really appears as stepping stones, before disappearing underground as armouring.

“This was a way of acknowledging the site context, and that it was a ‘constructed’ project trying to recreate natural processes,” Wright explains. “It also helped maintain the large conveyance capacity of the culvert.”

It’s the project’s considerations for delight and wildness, though, for human and non-human ecologies, that are what elevate it beyond a utilitarian exercise in filtration—what might otherwise be a contemporary take on the monofunctional “1970s special”.

“The integration of landscape architecture thinking helped guide the overall planning,” says Wright. “There has been a level of thinking about how people use space that you might not normally find on a solely engineering-led naturalisation project.”

She points to a bridge crossing located to maximise morning sun on an adjacent pond, so that early morning walkers and kids heading to school catch a twinkle of sunlight on water; a new bike path that shoots north of big existing trees, to allow a secondary footpath to duck south of the trees to a secluded, shady spot by the creek.

Then, there are the non-human inhabitants. In 2018, Ipswich council conducted a survey of fish life in the creek and found nothing. In May 2019, by the end of the first two stages of development, they recorded 874 fish, with six native species found including carp gudgeon, fly-specked hardyhead and longfin eel. Back on land, meanwhile, there are reports that a big male kangaroo has now adopted the site as his own, and that bird life is thriving.

This is multifunctional hydrological infrastructure for both human and non-human alike, built less through the pouring of concrete than through the design of a dynamic system—or as Hoban describes it, “by letting a creek be a creek.”

The fourth and final stage of project construction is due to complete in 2021, bringing the total length of revitalised creek to 1.6km.

‘Design and development’, of course, will be on-going.

Maitiu Ward is a publisher and editor of Foreground.