More than grass and trees: parks changing Australia

A joyful new exhibition has just opened at the National Museum of Australia, featuring a series of parks from cities across Australia that were once unprepossessing chunks of land.

The sites featured in the exhibition Places Changing Australia, include a former railway yard, a decommissioned petroleum distillation site, a couple of dockyards, an abandoned brickwork factory, some unloved streets, various industrial wastelands and a sand mine… not the kind of places where you would expect to find much joy. But that’s what happened next. All thirteen sites went from dust, bust and rust to become popular public parks.

Far from the conventional idea of parks being just places with grass and a few trees, the parks exhibited in the museum’s Circa Gallery represent a diverse and impressive collection of case studies that illustrate the exhibition’s title and theme. So why are these parks so important?

Paddington Reservoir Garden, Sydney by TZG Image: Tristan Davey

Canberra National Arboretum by TCL Image: Hennicke.

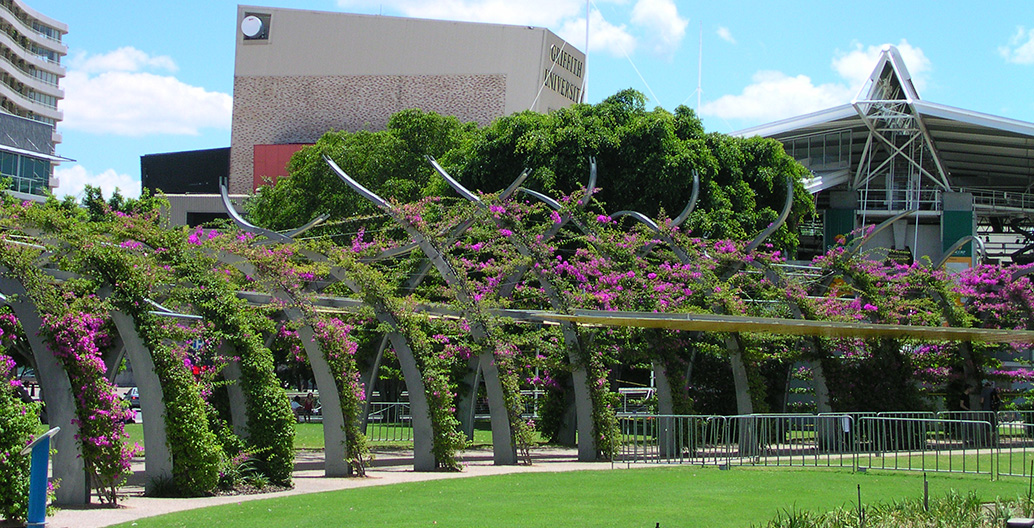

Southbank Parklands, Brisbane by Gillespies Australia (now EDAW) Image: Brewbooks

Darwin Waterfront Public Domain, Darwin by HASSELL Image: Brett Boardman

Australians have long been a town-dwelling lot. Our hearts might be by the beach or in the bush, but our bodies are in the city. Over the past half-century our cities have swollen, as great waves of us have moved from the inner-city to the suburbs, from the country and indeed from other countries, to the big smoke and to its expanding edges. Great parks, like those in Parks Changing Australia, help us absorb growth while keeping our cities liveable. They help us live good urban lives.

We can live cheek-by-jowl with each other so long as we have places of respite. We can live our busy, separate lives so long as we have places to come together. Great parks provide both.

The same goes for streets. When we only make space for vehicles, our cities are poorer. However, if we focus our care and attention on making space for people to walk comfortably, sit safely, find moments of delight, and enjoy moments of shade or sunshine, our city streets become places we want to linger.

Parks Changing Australia is a celebratory exhibition and rightly so: the projects showcased have demonstrably transformed, and continue to transform, the cities where they are located. They bring moments of joy, excitement, tranquility, and contemplation to millions of people. They are working hard. Not content to merely look good, they are performance landscapes and pieces of urban infrastructure, as important as roads and trains, schools and hospitals.

When we invest in these performance landscapes we are investing in the means to help clean air and reduce the increased temperatures found in all hard-paved urban areas. We are investing in the ability to clean urban stormwater and manage local flooding. We are investing in a reduction in our public health costs by making places that are good for our bodies and minds. Accessible, connected and inviting, parks make it easy to be active, and a growing body of evidence shows that access to green places is good for our mental health too.

Prior to their revitalisation, many of the places featured in this exhibition were bits of land that nobody wanted. They had previously been deemed too dangerous, too polluted, too inaccessible or too ugly. Transforming these unwanted spaces into successful parks takes courage on multiple fronts. It takes creative courage for the landscape architect to see a crumbling industrial relic or expanse of baking hot concrete and re-imagine it as a place for all to enjoy. It takes political courage to conserve a parcel of prime waterfront land for long-term public use, rather than quick development benefit. It takes financial courage to build a new park and then fund its ongoing maintenance.

If great parks tell us about ourselves then these transformed parks, which have required considerable courage from multiple parties, remind us that Australians value places where we can come together to play. Parks are one of the most democratic spaces in our cities, because everyone has the right to visit a public park.

Seeing such success, spanning many years of investment in parks, the obvious question is what’s next?

Over the following fifty years another 24 million people are expected to join us, doubling the Australian population. Who are they, where will they live? What will constitute a great park for them? Where will our next great parks be and what will they look like? How will they situate themselves in relation to this ancient continental landscape and the critical challenges of climate change?

If urbanisation and suburbanisation continues to expand on the country’s coastal fringes, what does a great park look like in shrinking regional centres? And if great parks truly are sites of democracy, who might feel excluded and how do we ensure they feel welcome? In answering all these questions, parks have the capacity to contribute enormously to ensuring our cities remain healthy, productive and inclusive of all.

A cynic might say that all it takes to be a great park these days is a coffee cart and free wifi, but this would fail to account for this wider contribution that parks make to Australian cities. The commitment shown by landscape architects to addressing past challenges, while preparing to face the ones ahead, will only become more relevant over the next fifty years, as parks continue to help sustain, connect and tell us about Australia.

Parks Changing Australia is open until 30 April 2017 and state-focused exhibitions are also on display in Virgin Australia lounges around the country.

The Parks Changing Australia are: Australian Garden, Melbourne, Ballast Point Park, Sydney, Birrarung Mar, Melbourne, Brookfield Place, Perth, Darwin Waterfront Public Domain, Darwin, Museum of Old and New Art, Hobart, National Arboretum, Canberra, North Terrace, Adelaide, Paddington Reservoir Gardens, Sydney, Roma Street Parkland, Brisbane, South Bank Parklands, Brisbane, Sydney Olympic Park, Sydney, Western Sydney Parklands, Sydney