“No skateboarding”: The politics of public space at Lincoln Square

Design can enable exclusion, as the redevelopment of a favourite haunt of Melbourne’s skateboarding community shows. We can and should do better, argues Mark Jacques in this public speech given in the newly ‘skate-proof’ Lincoln Square.

[The following is an edited extract from The Politics of Public Space – Volume One, published by OFFICE and available now.]

I’ve chosen to be here tonight, in Carlton’s Lincoln Square, to talk about the deliberate changes that have recently been undertaken to this area and the consequences of those changes on the public life of this part of the city. Before 2016, the experience of this space was a very different one to what we see tonight, so too its relationship to the Swanston Street spine. A series of design moves have been made that quite deliberately exclude the occupation of one group of people and privilege another kind of occupation. What is essential to note is that this exclusion has been enabled through design – the thing that we do.

So, if you have the ambition to work in the public realm, this dilemma will arise at some point in your career. If there is anything that I’d like to come out of tonight, it is that you become aware and critical of the tactics of inclusion and exclusion within the city, how they work, and what your role is when generally working for those that have power, at the behest of citizens that don’t.

In the last 20 years, the city around the Lincoln Square has redeveloped substantially through a series of projects immediately adjacent to it – coincidentally all designed by Hayball. The Europa Apartments, yonder up Swanston Street are from around 2003. The Seasons Apartment building was completed around 2006. The Canada Hotel site in 2009, and finally the Bravo Apartments in 2014. Arguably, the Bravo Apartments coincided with the death of Lincoln Square as we knew it, bringing in new residents including Roz Hansen, a well-connected and long time planning advisor for the State Government of Victoria, who saw the street scene of Lincoln Square as ‘urban anarchy’ and led the charge for its redevelopment, stating with no irony that sharing the space with skaters affected ‘shared spaces’. Then Lord Mayor Robert Doyle was groping at a greater truth when he said of the skaters in 2016 that “time’s up for this selfish minority who tried to capture a part of the city for themselves … It’s just not on”.

Before 2016, Lincoln Square was a popular skating spot that drew international skaters. The square is now un-skateable because of treatments such as these. Image: OFFICE

Mark Jacques speaking as part of The Politics of Public Space lecture series. Image: OFFICE

Newly developed apartments opposite Lincoln Square, Carlton. Image: OFFICE

This is a problem of adjacency – an itch between an agent of State Government right there [pointing to Bravo Apartments] and a pre-existing population of skaters who were right here [pointing to Lincoln Square]. The problem is fueled by the City with the apparent language of inclusion (“shared”, “selfish minority’ etc.) but occasional design actions of deliberate exclusion, in 2016, the City of Melbourne councillors voted to redesign the park to make it unsuitable and unattractive for skateboarders.

As Vito Acconci reminds us, “Public space is not space in the city but the city itself”. Exclusion in public space undermines the city and undermines what makes the urban – the itch of adjacency. The city is proximity to the unfamiliar, encounters with the stranger and vicinity to the other.

This is the kind of argument that is made by people like Iris Marion Young when she describes the city as ‘heterogeneous, plural and playful, a place where people witness and appreciate diverse cultural expressions that they do not share and do not fully understand’. It might be skaters, or it might be the poor, the old, the new immigrant, the suburbanite, the redneck – cities that exclude adjacency with those that are different, become increasingly crowded with people who think, live and vote the same. They enable the kind of homogeneity where it is increasingly difficult to encounter those who are different from ourselves and increasingly harder to develop ways of exchange with those who are different from ourselves outside the knee-jerk reactions of outrage or the muting of cancel culture.

Inclusion, therefore, is an engine not only of public space but of public life and of the civic. Private spaces become public when the public is able to annex them. The annexation is a by-product of design. Public space becomes private when the public that has it gives it up, or is designed out of being able to claim it, which I would argue is what has occurred here in Lincoln Square.

The kind of design moves that I’m talking about might be providing skateable surfaces like this [points to the asphalt of the street] or non-skatable surfaces like that [points at the new lawn and skate barriers that were installed in Lincoln Square]. But they also include other kinds of tactics – the kind so comprehensively documented by Interboro in The Arsenal of Exclusion & Inclusion – including adverse possession laws, zoning laws, commit no nuisance signs, alcohol-free zones, armrests on benches, bike lanes, bollards, busking bans, muzak, clear zones, covenants, the cul-de-sac, fences, housing co-ops, no loitering signs, corridors, privately-owned public space, street trading zones, smoking bans, tenant communities and owners corporations.

An important book for those of you who are interested in the agency of public space is the Practice of Everyday Life written in 1980 by Michel de Certeau, which in some ways anticipates and describes the idea of habitual power, control, inclusion and exclusion in public spaces.

Certeau makes the distinction between the producers of culture (the powerful) and the users of the culture of the city. The producers of culture exercise agency over the city through strategic imposition, so the idea of a kind of order from above, generally at the scale of the precinct or the metropolis. In contrast to this, Certeau characterises the domain of the non-powerful users of culture not as strategy, but as tactics.

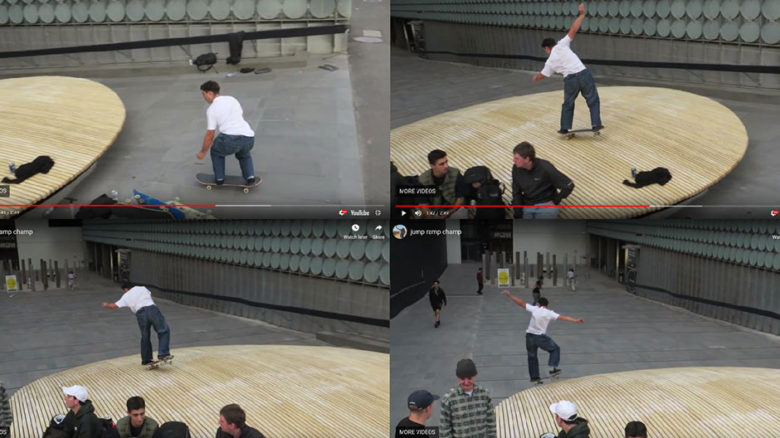

Stills from Jump Ramp Champ, an OPENWORK design intervention at RMIT's Design Hub, just down the road from Lincoln Square. Image: Theguystokeschannel

Demolition works at Lincoln Square. Image: Benjamin Thompson

Lincoln Square's varied ground treatment to deter skateboarders. Image: OFFICE

So, there’s a distinction between strategy as a big picture of how the city is organised, and the tactics of those that generally don’t have the power to alter the city, making the city in their own mould. The book centres on the idea that the weak deployed tactics to alter utilitarian objects, street plans, laws and language, in order to make them their own. So in a space like Lincoln Square, we now see what de Certeau might call “the weak tactics of the strong”, in this case, the strong being City of Melbourne – blunt attempts to restrict public access to public space. Opposing this, we await what he might call “the strong tactics of the weak” – ways in which skaters and others will annex the space and bring it back into a more nuanced, inclusive and itchy public life of adjacency and difference.

The design of the public realm is an attempt to locate oneself between these two kinds of behaviours – the “weak tactics of the strong” and the “strong tactics of the weak”. In practice, we are cast in the role of acting both for the public good and at the behest of private capital, a role that requires demonstrable creation of value and amenity for both constituents, often with promiscuous loyalties. Despite our best efforts, we have to acknowledge that we’re not given sole authority in the public realm nor are we part of a particularly powerful guild.

Instead, we must win agency on projects through tactics of persuasion and arguments – often exercising influence with covert strategies and persistent advocacy. In our case, we deploy physical form to make the limits of public and private realms ambiguous. Within this ambiguity, we see a site for exchange, for the physical presence with the other, for shared experience and for the chance encounter. Our intention is to deploy physical and spatial devices that allow those sites to be annexed and occupied by the users of culture in the city. We see uncertainty as arguably the primary engine of public life and the uncertain boundary is an instrument for both the enquiry into and the making of, the city.

What I’m proposing (in the spirit of Certeau) is that in the design of the public realm that you accept the brief and capital of the powerful, but do so by working as if you are weak. Understand the strategies of superimposition and control within the city well enough to warp and convert them to other ends, and deploy tactics not of exclusion, but of inclusion that enable ordinary people to behave not merely as passive and submissive consumers but as active agents, who can manipulate the environments around them through everyday actions.

The trick is in making a project just awkward enough to prevent easy reabsorption into the order of power and commodities. Within this awkwardness is a space for annexation and the space of occupation and adjacency.

To conclude, I’ll return to Vito Acconci who talks about public spaces as an analogue of sex – that the private realm is one of monogamous relationships, but that public space involves the surrender of purity and all the comforts of the private. The private is the space of control, the public of surrender, infidelity and exposure. His litmus test for space in the city is that its public only if it can be used to organise a quick fuck or for a conspiracy. There’s nothing preordained or naturalistic about the ability of public space to work this way. It’s not spontaneous, it’s the product of human design and it’s willed through decision and action, and as participants and the authors of the city – the action is yours.

–

This is an edited excerpt taken from ‘NOT IN THE CITY, BUT THE CITY ITSELF’ by Mark Jacques from The Politics of Public Space – Volume One. The Politics of Public Space is a quarterly publication of transcripts published by OFFICE. Volume one is available now.

Mark Jacques is a director of OPENWORK, a studio for landscape architecture, urban design, research and speculation. He is Professor of Architecture (Urbanism) Industry Fellow at RMIT University’s School of Architecture and Urban Design.