“Gardens aren’t just a retreat, but an active advance”

In her work with cancer charity Maggie’s, Lily Jencks is helping to raise awareness of the powerful role that landscape architecture and design can play in health care delivery.

Her mother Maggie was an artist, garden designer and author of a seminal book on Chinese gardens. Her father Charles was also a landscape designer and a prominent architectural historian and post-modern theorist. So when asked if she’d ever seriously considered an alternative career, UK-based architect and landscape architect Lily Jencks laughs.

“Yes, indeed I tried not to do architecture. I was lectured so much about architectural history while I was growing up, it rather put me off,” she recalls. After a stint in high school as an intern with a marine biologist, which she says, “is not as exciting as it sounds,” Jencks still hadn’t consciously decided on a career trajectory. But she did concentrate her studies on chemistry, biology and art. “I suppose,” she admits, “in that group of subjects there was clearly a link between the maths-brain and the art-brain, which is one of the great pleasures of studying and practicing architecture.”

Maggies Gartnavel in Glasgow, by Lily Jencks and OMA.

Maggies Gartnavel in Glasgow, by Lily Jencks and OMA.

Maggies Gartnavel in Glasgow, by Lily Jencks and OMA.

And Jencks, who now teaches at the Architectural Association in London while also running her own award-winning architecture and landscape architecture studio, has not regretted going into the family business.

“Architecture – and landscape architecture, perhaps ‘design’ more generally – includes so much of human existence,” she explains. “It provides a way to think about many subjects, from how a city functions in the more urban end of architecture, to how materials should join or a brick course can catch light. Much of the pleasure is in the range of scale that architecture, and landscape, engage us with and the myriad issues that we try to address as designers.”

One of the issues that Jencks addresses in her work is the synergistic relationship between architecture, landscape and health. Jencks explains that her design philosophy is to focus on “what a building or landscape can make you feel, rather than just on its function or what it looks like.” This ethos is evident in all of her work, but can be seen perhaps most clearly in her work for Maggie’s. Named after her mother and founded by both of her parents, Maggie’s is a charity that provides free support for people living with cancer at more than two dozen centres in the UK and three, to date, elsewhere.

From Edinburgh to London, Hong Kong and Tokyo, Maggie’s centres provide quiet and calm, domestic-scaled spaces within the hospital grounds of some of the busiest cities in the world. And while there may never be a good place to receive bad news, Maggie Keswick Jencks knew, from personal experience of her own terminal diagnosis, that some locations are definitely worse than others.

The story of the terrible moment of inspiration for what was to become the Maggie’s centres has been oft repeated: in May 1993 Maggie was told that her breast cancer had spread and that she had just months to live. Then she and Charles were bustled into a hospital corridor and left to deal with this irrevocable news in a cold, clinical and very public space. The couple, with their longstanding passion for design, knew that they might not be able to change Maggie’s cancer prognosis, but they could help others by providing a better place to receive support.

Maggie defied her brutally short prognosis and died two years later in July 1995. In November 1996, the first Maggie’s centre opened in Edinburgh. From the very beginning the aim was to provide warm, hospitable, domesticated spaces for education, catharsis, conversation, and healing. With this in mind, the kitchen and the garden are at the heart of all the Maggie’s centres, and their welcoming atmosphere has always been nurtured by architects and landscape architects working in tandem. Maggie’s integrated indoor and outdoor spaces have been designed by some of the biggest names in the business, including Charles Jencks himself (Inverness), Zaha Hadid (Fife), Foster + Partners (Manchester), and Arabella Lennox-Boyd (Dundee).

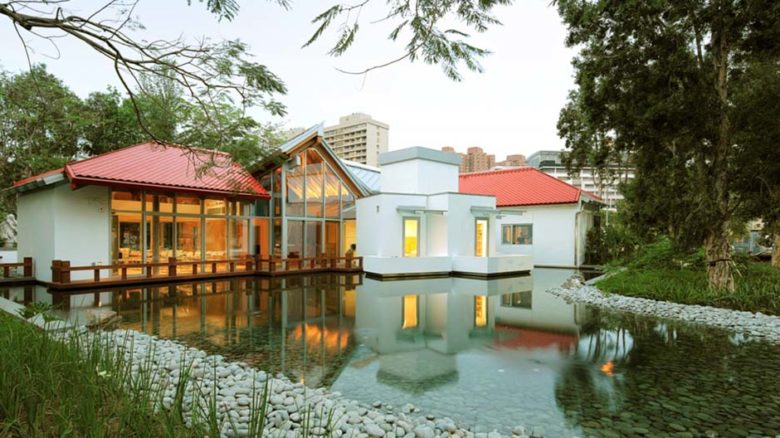

Maggie's Hong Kong by Lily Jencks and Frank Gehry.

Maggie's Hong Kong by Lily Jencks and Frank Gehry.

Maggie's Hong Kong by Lily Jencks and Frank Gehry.

Lily Jencks (who was still a teenager when her mother died) joined this impressive list in 2011 when she designed the garden for the Maggie’s at Gartnavel General Hospital in Glasgow, in conjunction with Rem Koolhaas and OMA. She also worked on the Hong Kong Maggie’s centre, which opened in 2013, this time with architect Frank Gehry (who had already worked on the Dundee centre). “In each case, the building was designed very much with the garden in mind,” Jencks says. “It is really important that we see the value and benefit of landscape, and see gardens as active, necessary, even urgent, places for design.”

As Jencks points out, the healing qualities of landscape are well known. In fact, a number of recent studies conducted by UK universities in York and Manchester, and Leuven University in Belgium, used Maggie’s centres as a case study. The focus and findings of these studies vary slightly, but they all highlighted the positive impact at Maggie’s centres of good design, integrated both inside and out. As Daryl Martin, Sarah Nettleton and Christina Buse, from the York group, put it in their 2019 Social Science & Medicine journal article, “Maggie’s Centres, we argue, are emotionally charged buildings that shape the ways in which care is staged, practiced and experienced; these buildings are affecting care, as it happens in everyday ways.”

Which was precisely what Maggie Keswick Jencks, and her husband Charles, envisaged. When designing the very first centre, Maggie insisted on the need for “thoughtful lighting, a view out to trees, birds and sky.” She was determined to create a healthy, healing space for people living with a terrifying disease. Now spread across the UK, and increasingly the world, her vision is a key element of the Jencks legacy; architecture, landscape architecture and positive healthcare are now all part of the family business. Charles died in late 2019, but their daughter Lily continues to keep up the good work.

Lily recalls that when she was working with Frank Gehry on the Hong Kong Maggie’s they drew inspiration from her mother’s 1978 book The Chinese Garden, which highlights the fact that these stylised gardens are a microcosm; a symbolic representation of something much larger. Maggie’s centres themselves can be seen in the same way. As small pockets of respite in which landscape and architecture work harmoniously together to promote wellbeing, they point to the importance of incorporating garden spaces into our urban infrastructure if we want healthy cities.

As Jencks, who is now vice president of Maggie’s, points out, “I work as both a landscape architect and architect, and I really value the different qualities each discipline brings. It is really important to me that landscapes are appreciated as the high-value places that they are.”

Paraphrasing the late artist Ian Hamilton Finlay, Jencks says, “I love that gardens can be, not just a retreat, but an active advance.”

–

Tracey Clement is an artist and writer based in Sydney, Australia.

This article is part of Foreground’s Transformative Landscapes themed series of essays. Lily Jencks will be talking at Foreground’s associated event at the NGV 19 March 2020. Click here for tickets.