Against everything: The curious case of Rushcutters Bay skate park

Contrary to popular belief, hordes of young skaters aren’t tearing up cities the world over. But a recent decision to forgo a skate park in Sydney’s affluent Rushcutters Bay highlights the tension between perception and reality.

The chances are, when you first picture skate culture, you’re not going to picture the dreamy, long-haired Californians of the ’70s complete with longboards. Depending on your media diet, you might picture adolescents tearing down city streets, or grouping around suburban malls trying to land their next kick-flip.

It’s easy to see how these perceptions linger. Pop culture’s narratives, expressed through songs, films, or television programmes, have frequently painted skate culture as something to be apprehensive about: urban punks rebelling against parents, forging new communities in spaces that city planners otherwise want left alone.

“The majority of people’s experience with skate-parks isn’t from lived experience,” says Dr Simon Sleight, senior lecturer of Australian History at King’s College London. His research extends to Australian urban history, and tells Foreground that the majority of skateboarding’s perceptions are plain old stereotypes.

“Most people would associate skating with music and experimentation – the latter of which is central to honing any skills,” he says, “And this ‘experimentation’ could be viewed as some gateway to sampling drugs or making inappropriate social bonds”.

American rapper Lupe Fiasco’s 2006 single ‘Kick Push’ is one of many examples in pop culture charting the challenges that present themselves when skating in the city.

These perceptions of course, don’t really match up with the reality of what the sport’s like today. In 2016, the International Olympic Committee voted unanimously to make it an Olympic Sport in time for the 2020 games and skate schools have opened up in Afghanistan, Cambodia and South Africa to improve youth empowerment.

Locally, Melbourne City Council has recently released its inaugural skate policy, one that signals moves to allow skateboarding and public space to coexist (including a dedicated 24-hour skate facility), reversing years of traditional antagonism towards the form.

Though, not all new stories are as positive. A curious case about a Sydney-based youth facility (otherwise labelled as a ‘skate park’) has exposed the sport (or the art form’s) lingering negative connotations.

A vintage image from a skate-meet in '70s California. Image: Judi Oyama via Flickr

Rushcutters' Bay Park and surrounds photographed in 1937.

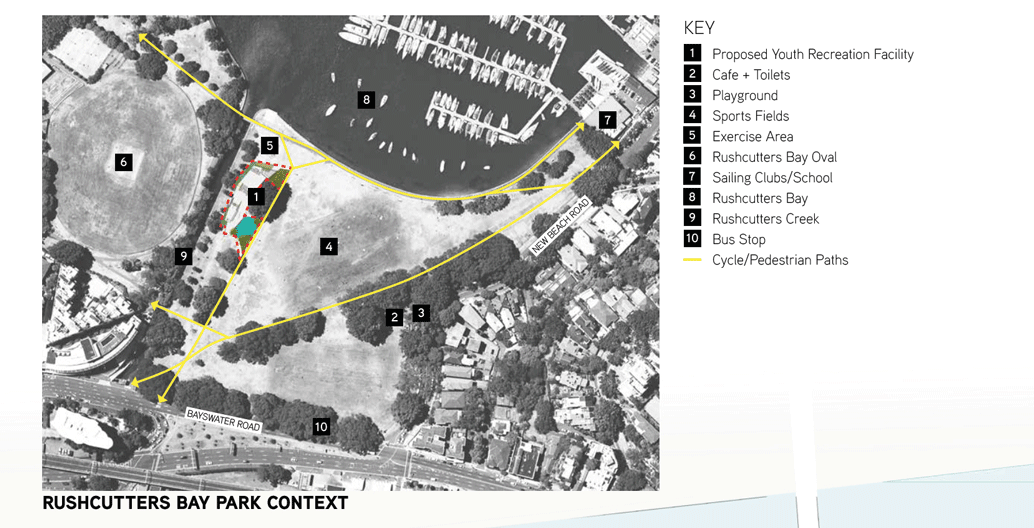

The facility proposed was going to take up less than 0.2 ha of the park's total 5.3.

One of the globe's most recognisable skate parks at Venice Beach, California.

In 2013, the harbourside council of Woollahra received a submission looking at skate facilities in the Paddington area from a local residents’ group called Skatecraft, largely made of under-18s. They argued for a designated skate facility for younger skaters (those between the ages of 8-14) making the point that most children of that age weren’t independent enough to travel on their own to other facilities.

Between 2013 and 2016, the council undertook a research and consultation process drafting plans for a potential youth skate facility. This honed in on Rushcutters’ Bay Park, a harbourside park bordering the City of Sydney and the federal electorates of Sydney and Wentworth (home to deputy opposition leader Tanya Plibersek and Prime Minister Malcolm Turnbull respectively).

Sitting among some of Sydney’s highest valued properties, the park sits in a beautiful stretch of the harbour city – flanked by period architecture and a marina, it’s perhaps not surprising that a skate park wasn’t welcomed with open arms straightaway. In fact, on 1 May 2017, after three years of consultation and $80,000 spent in research, the council voted 10-1 to ditch the plan and proposed that the skate facility be moved to Centennial Park (a plan already underway as part of the park trust’s masterplan).

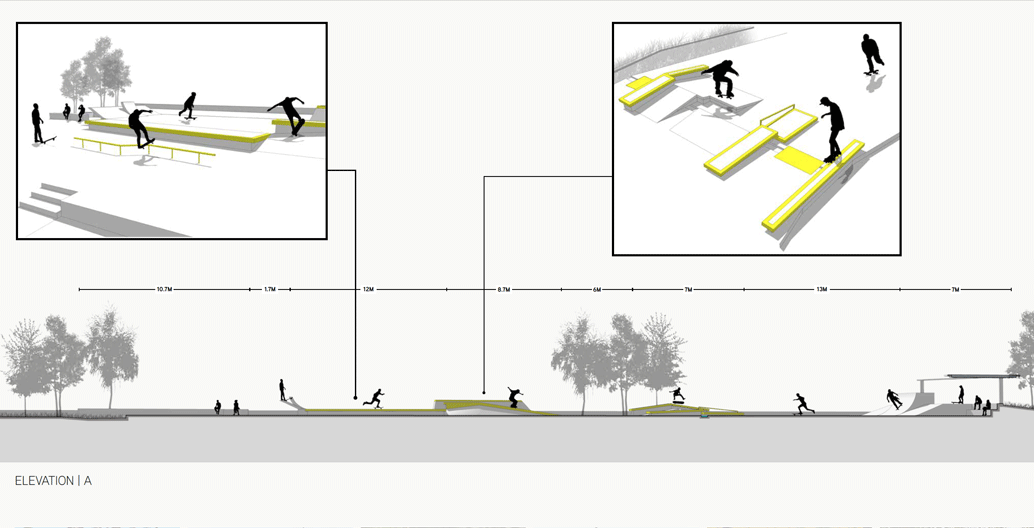

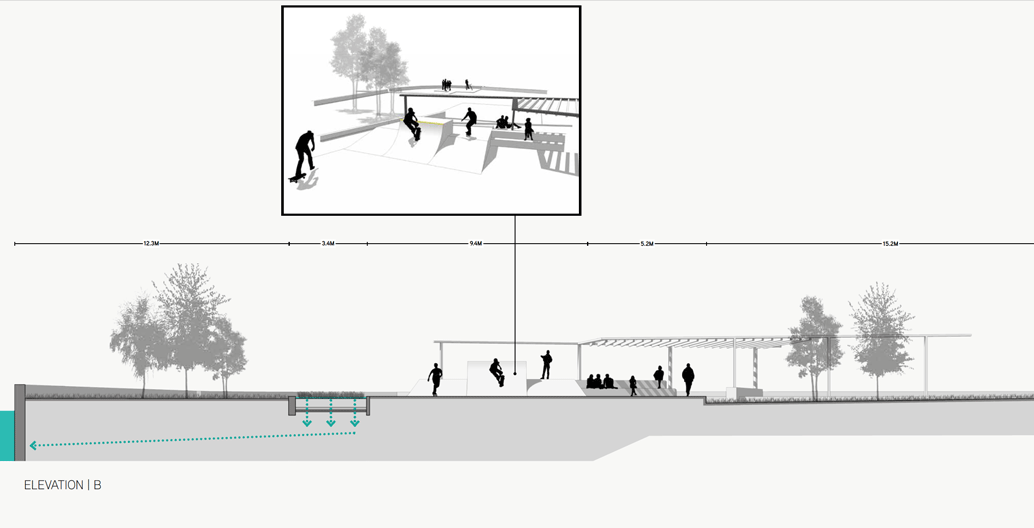

The slopes illustrated here reflect the space's programming for younger skaters.

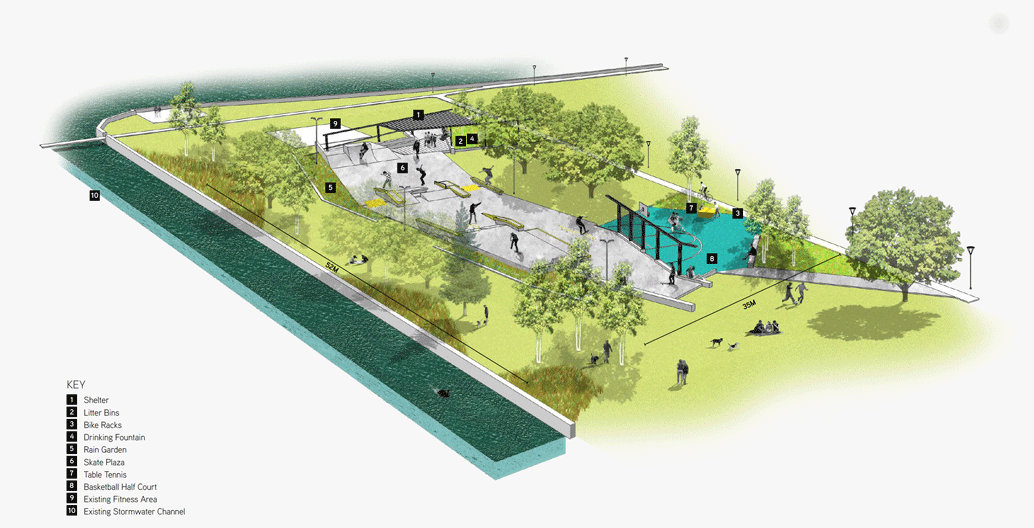

A render of the youth facility's proposal from the facility's consultants, Convic.

A bird's eye view of the facility, complete with a basketball court.

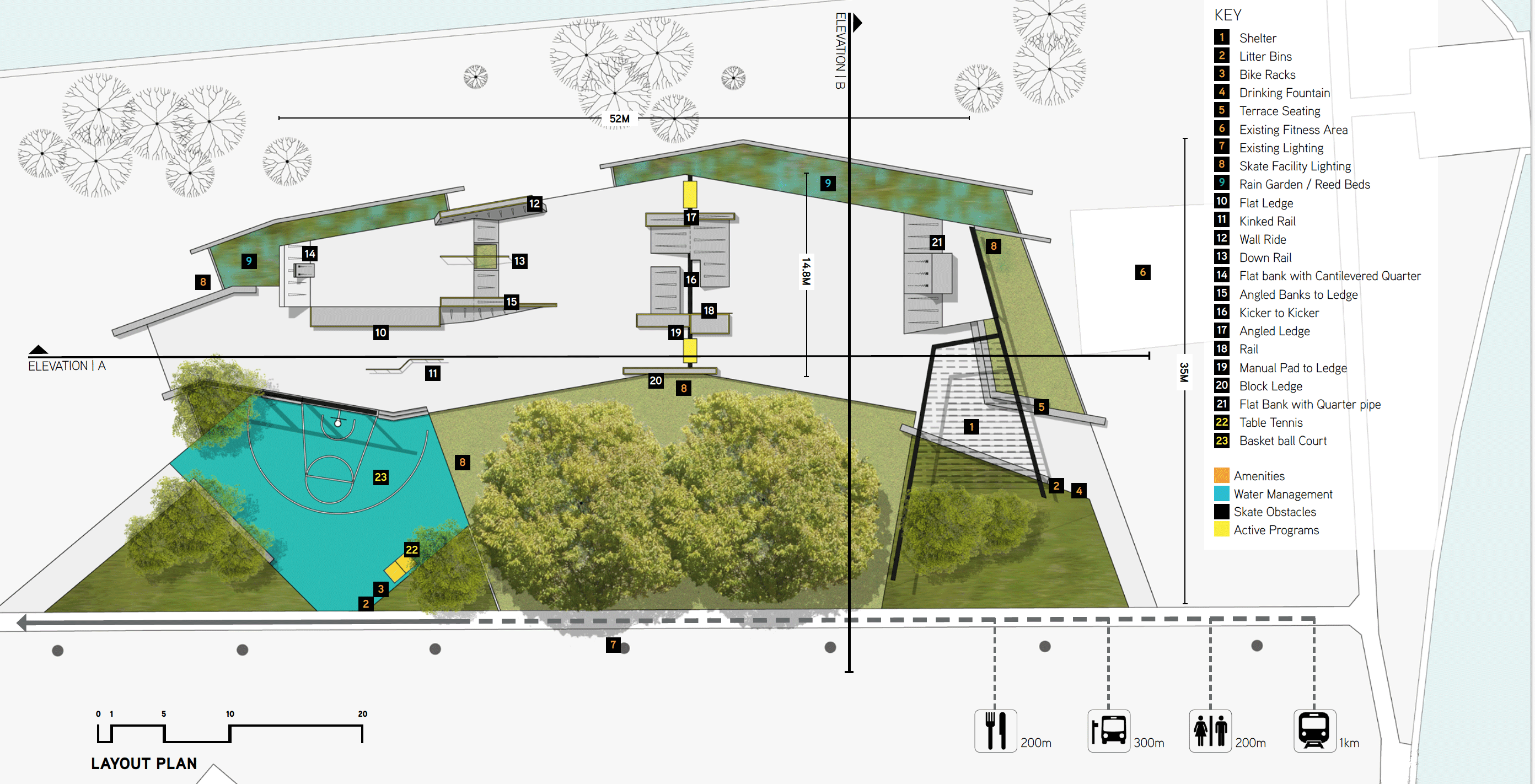

A cross-section of the facility from another view, illustrating a communal viewing platform.

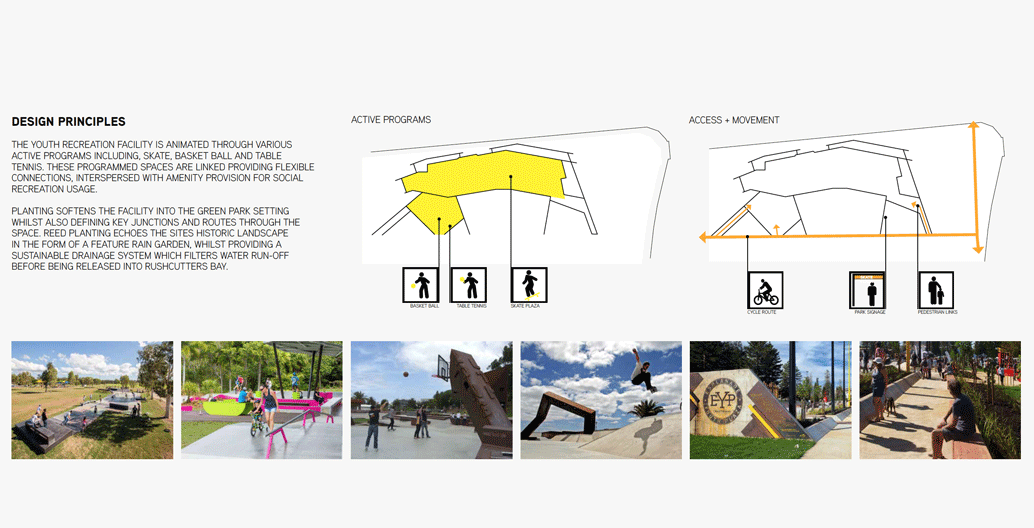

Basketball, table tennis and junior skating all were planned for the facility.

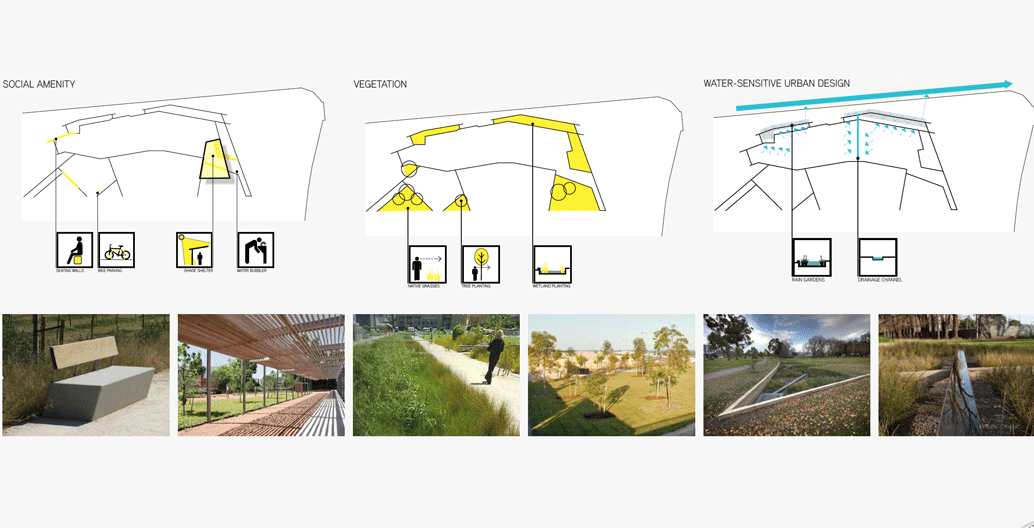

Additionally, there were going to be rain gardens to incorporate water sensitive urban design principles.

“I doubt the majority of objections were informed by watching YouTube skate videos or reading specialist skateboard magazines,” says Sleight. “One must assume they’re recycling stereotypes that are produced in the media, where the Australian popular press is particularly conservative compared with the rest of the western world. Perhaps that has an effect in one way or another.”

The now-deposed Rushcutters Bay proposal garnered 278 objections (including that of the Prime Minister himself) compared to 82 letters of support (including that of the deputy federal opposition leader, Tanya Plibersek). In a council report analysing the proposal bid, they identified the majority of these objections were “concerned that the proposal was not in the character of the Park and would reduce amenity. Concerns raised were related to noise pollution, reduction in open green space and trees and anti-social behaviour”.

“Council staff do not believe that the proposed facility would foster anti-social behaviour,” says Paul Fraser, the manager of Woollahra City Council’s Open and Space and Trees division tells Foreground.

“The facility was targeted at the 8-14 age groups and skate elements were only one part of the proposal. Unfortunately this element of the proposal had the most negative feedback. Staff realise the benefits of these facilities to a local community.”

Despite the council’s best efforts to communicate to residents and park users that the park would take up less than 0.2 hectares of the park’s total 5.3 hectares, objections still were raised about the facility’s impact on open space. But, judging from the council’s analysis on objections, it would appear as though access to open space wasn’t totally front of mind.

In his letter sent to the council prior to their decision, Turnbull noted the park was “used by children and adults alike as an extension to their own living rooms”, adding that the park would not be “sympathetic to how the park is currently used”.

Michael Spackman, director of landscape architecture practice Spackman Mossop and Michaels, and proposal advocate, noted there were other things at play.

“A lot of it came down to property values, and preserving personal property values because of the views of the park from certain properties,” says Spackman.

He has been doing pro-bono advocacy for the groups invested in seeing this facility built since the proposal first caught the press’ attention – thanks in no small part to the PM’s intervention. He notes that the park will be on the backburner for the time being, unless these groups make some noise around the council’s local elections, scheduled for September 2017.

“Philosophically parks are seen through a 19th-century lens,” Spackman says. “They’re a nice place to walk a dog for two people… now is that the best use of public money? That view marginalises whole groups of society, and that’s where the debate about where parks are going in the future comes in.”

At present, the council is “in discussions” with the Centennial Parklands trust, who have had plans to built a skate facility as part of their 2040 masterplan. This facility falls outside of the council’s municipal area, though it borders its southern ward, Paddington.

While these qualms echo traditional fears of skate culture, Sleight argues that those arguing against a skate facility because of “anti-social behaviour”, often perpetuate the conditions which produce anti-social behaviour in the first place.

“Efforts to discourage people from public space makes it less safe,” says Sleight, “When public spaces are frequented and bustling brings a collective safety… it’s when spaces have to hire private security guards makes them more worrying to be around”.

The conception of “anti-social behaviour” from certain residents cited fears of drug use, crime, and graffiti – behaviour not nominally associated with 8-14-year-olds. Meanwhile, it is notably ironic that the Woollahra use/possession rate for cocaine is 12 times the state average, coming just behind the Sydney CBD.

“In this case, the term ‘skate park’ has derailed the process,” says Spackman. “It was always going to provide more than just skating, but the tag was an easy way to put it in a box and dismiss it. Obviously the communication of what this is about – about getting kids involved in planning – got lost.”

The closest skate facility to Paddington then, and now, is Bondi Beach’s Skate Park – one usually reserved for older skaters and about 20 minutes away by bus. While certain objectors noted they were “disappointed for the kids”, the net affect of this decision will reverberate for years to come.

“When this vote went to council, all of the schools said to the kids they should check out the meeting to see ‘democracy in action’,” says Spackman. “So all of these kids trooped down with their families and basically the whole proposal got turned around. All of these kids went home pretty disillusioned about the democratic process.”