From asphalt jungle to edible landscape

As the inaugural winner of the Australian Institute of Landscape Architects and 202020 Vision’s My Park Rules competition, Marrickville Public School’s new park demonstrates why green space and spaces for play are vital in the inner-city.

Unlike its television counterpart, My Park Rules is anything but a cutthroat cooking competition designed to pull ratings – albeit, as luck would have it, it has produced something both photogenic and delicious. The initiative, a collaboration between the Australian Institute of Landscape Architects (AILA) and 202020 Vision, has seen Australian schools and their students submit proposals to turn their exhausted or underutilised outdoor spaces into vibrant community parks.

In late 2015, public voting whittled competition entries to down a pool of seven finalists (each representing an Australian state or territory), with the winning Marrickville Public School entry advocating for a greening of the school’s formerly barren courtyard.

“The kids wanted to get rid of their asphalt jungle and have some nature to reconnect to,” Julie Lee, director of landscape architecture at Tract Sydney and leader of the Marrickville design team, told Foreground.

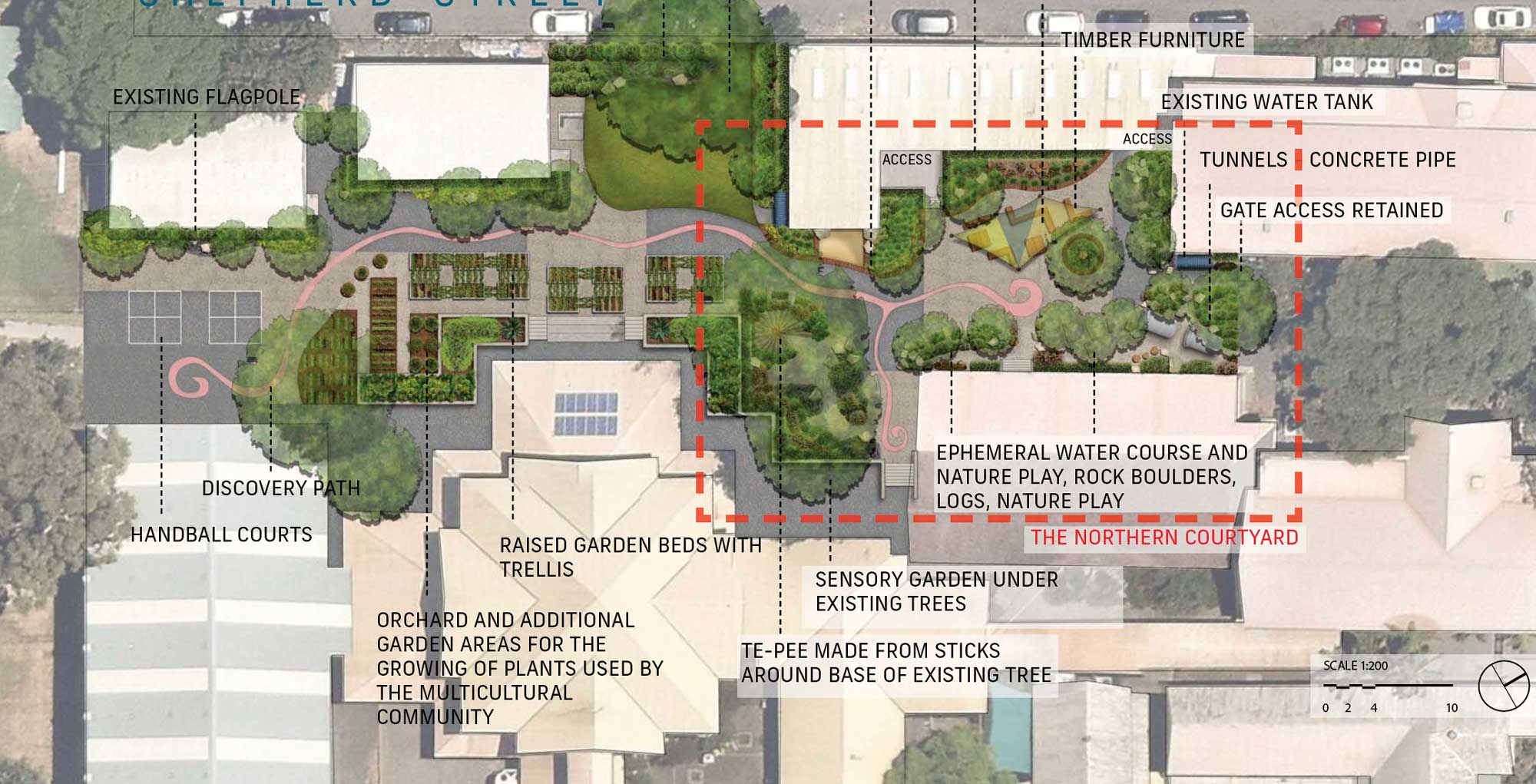

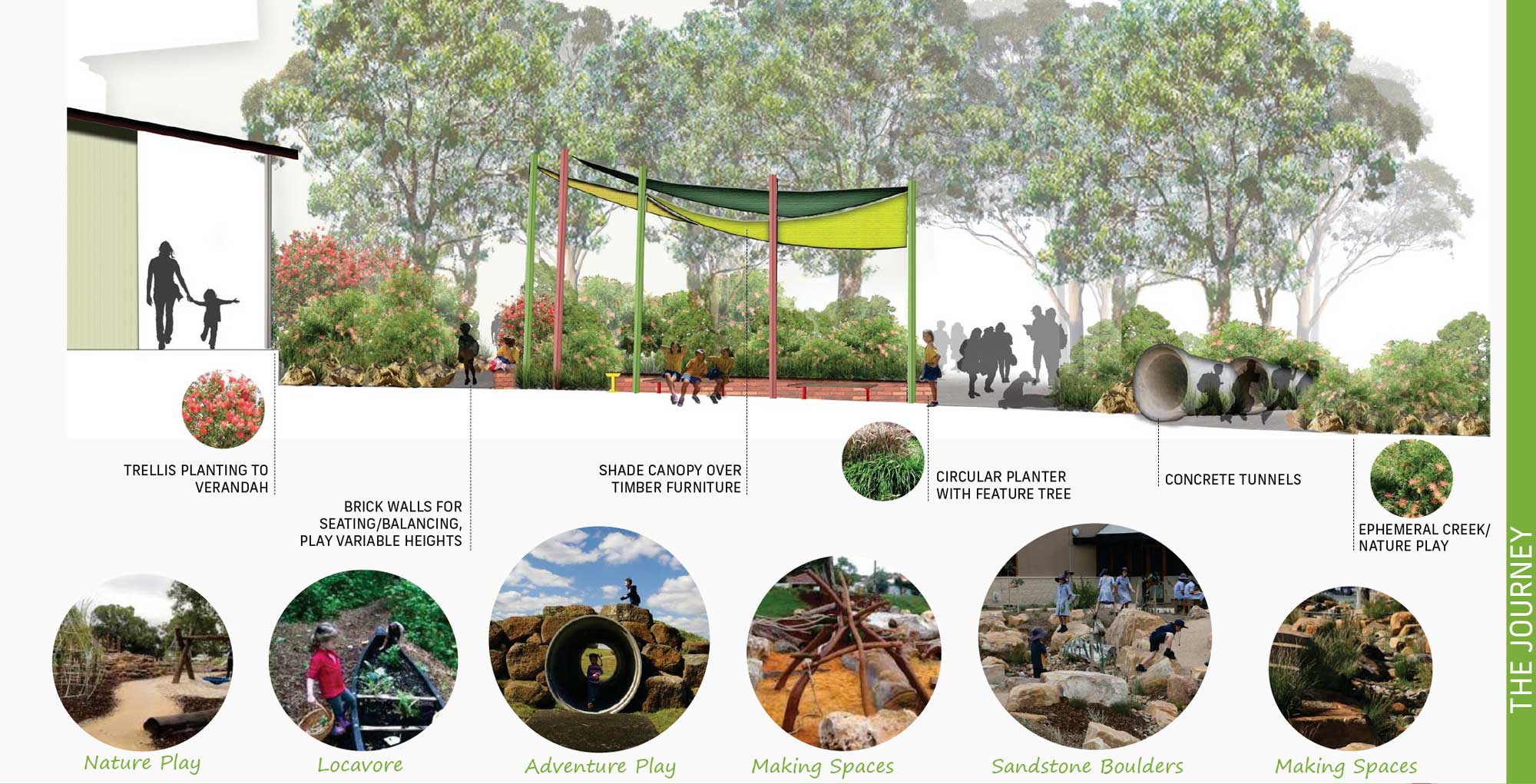

What resulted, with direct input into the design from the kids themselves, is a $100,000 living ecosystem replete with trees, climbing plants, garden beds, and concrete pipes for play.

The barren courtyard in need of revitalisation.

The courtyard prior to the build.

The community consultation involved children, parents and teachers.

The intention behind the masterplan was to let children gather and adventure until the bell went.

The various objectives of the revitalisation plan.

The plan had to master the tricky balance of keeping things safe while also allowing for risk.

Tract identified that 65 percent of the student body lives in medium or high density dwellings, with 60 percent of that group coming from communities where English is not the first language spoken at home.

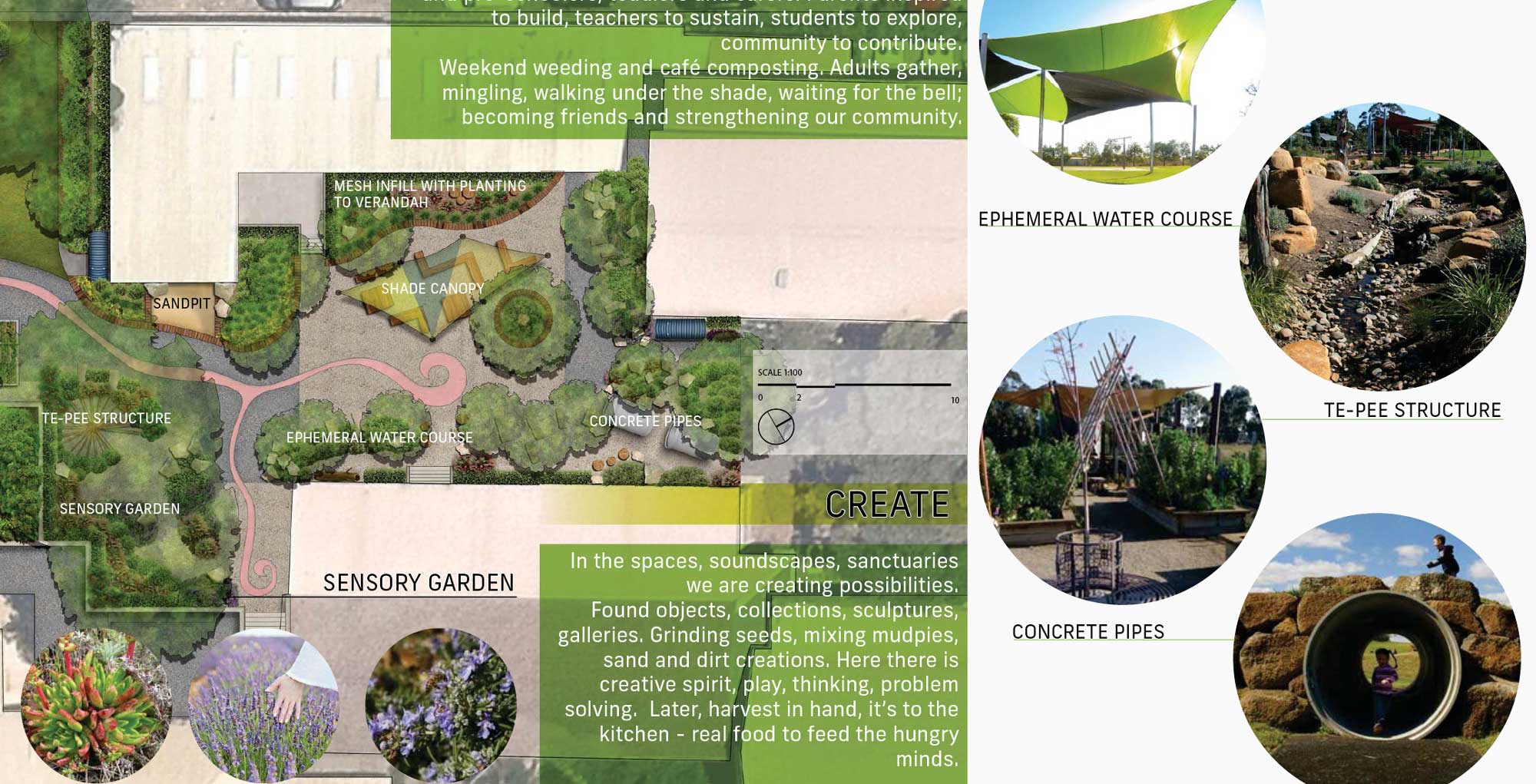

“With the project, there was an understanding that we needed to incorporate elements of what people had been doing culturally at home,” Lee said, “So we’re trying to see the park as a platform to reinforce the multicultural aspects of the school.”

The revitalised courtyard features planters of coriander, carrots, warrigal greens, apples and wattle seeds. This edible landscape will soon be accompanied by a community kitchen that will be open to the public on weekends.

“When we were in the planning stages, the park was designed to integrate with the kitchen,” says Lee. “So say if Marrickville’s Polynesian community wanted to use it like a local park, they could.”

It’s this accessibility that convinced the seven-person jury of the merits of Marrickville’s entry.

The incorporation of edible plants means the school can contribute to the growing “locavore” movement, which promotes diets made up of locally grown or sourced food. More importantly, it provides an opportunity for students to learn about food production, despite living in a highly urbanised environment.

“The school was already giving excess herbs to the local coffee shop, and in turn, the green waste from the shop was being recycled with the school,” Lee says. “These processes help kids learn about food in a way that’s beyond the supermarket”.

Given that Sydney’s inner west is retrofitting its industrial spaces with residential ones – and plenty of young families are moving into them – parks like Marrickville Public School’s also give locals the opportunity to strengthen biophilia in the community.

The former asphalt courtyard now gives way to gravel and a sandpit.

The finished product.

Chief Commissioner of the Greater Sydney Commission, Lucy Hughes Turnbull AO and The Hon Anthony Albanese MP.

Hughes Turnbull AO, speaking to pupils at ground breaking.

“The school is in an industrial part of Marrickville where there’s not a lot of green that can happen,” says Lee, “but this a good example of the way schools are re-opening themselves up to the community, and trying to make an asset contribute more to community growth.”

As Lee points out, because the students were directly involved in the process, they have ownership over the outcome. This is critical, as it’s the pupils of Marrickville that will be the ultimate enablers of the park’s potential to drive community growth, as they pass on their landscape knowledge to their families and younger peers. While they probably aren’t going to come out of their My Park Rules experience with a regular cooking column or TV spot, they and their neighbourhoods could be literally reaping the benefits of this verdant community hub for years to come.

––

Foreground is produced in partnership with the Australian Institute of Landscape Architects (AILA).