TCL’s Lisa Howard on gender in landscape architecture

As part of International Women’s Day 2018, Foreground speaks to TCL’s director, Lisa Howard, about her experiences working as a woman within Australian landscape architecture and how the design professions might be able to build gender equity.

Foreground: As you’ve progressed as a student and then professional in landscape architecture, have you noticed any gender imbalances?

Lisa Howard: At university, I think we had a fairly good balance and I have very fond memories of a lot of female lecturers and supervisors throughout my entire education. What was most noticeable starting out as a young female graduate, was that when you turned up to meetings virtually the entire room would be full of men, except for myself – so we’re talking engineers, developers, project managers, and fellow designers.

One of the things anyone has to do starting out is find their own voice as a professional, in order to assert themselves. I made sure I made room for my voice among those men – to not feel intimidated, to speak up and hold my ground. I find there’s often a subtle level of intimidation that can come across from men in meetings when they’re trying to push a point – talking over the top of you, using a raised voice or a condescending tone.

FG: In the built environment industries, I imagine the presence of young female practitioners would be challenging to the traditional notion of ‘masculine’ environments, such as the construction site or the boardroom.

LH: Definitely. It’s been more noticeable as I’ve progressed in my career, because I’ve experienced situations where men on a construction site introduce themselves to my junior male colleague before me. They automatically assume that he’s my senior, and it’s only when we’re walking around that they realise I’m the one answering questions and most informed about the project. It’s a subtle but strange thing where you’re in contexts where people express their unconscious bias by directing questions to your male colleagues first. And it is not uncommon to be introduced to a new male professional, and have my hand almost crushed by their handshake.

On smaller projects, and on some of the residential jobs I’ve worked on, I’ve walked into tea rooms and there are half-naked women plastered on the walls – this has happened only in the past few years. Regardless of whether it’s a man or woman exposed to that, you’ve got to ask yourself: is this the impression you want to be giving? The boys club still exists, where things are all just a bit of a joke.

FG: I imagine coming up through the ranks you would’ve had to fight many a boys club in your time, and probably still are in certain contexts.

LH: The boys club definitely still exists – we are expected to lean in, but we are rarely extended an invitation, and often excluded – it may not always be deliberate. The networks, lunches, after-work drinks groups are less inclusive.

FG: In most industries, women start to disappear from the workplace as they age, which some evidence suggests relates to childbirth and raising young families, in part. What’s been your experience seeing female peers and friends within landscape architecture raise children later in their career?

LH: My husband works in one of the big four banks and they value and manage ‘work-life’ integration, where flexible work including part time and job-sharing is the norm, even at executive level. We all multitask as designers – that’s just what we do. During the week you might be working on five different jobs as a designer. So, the perception that “women can’t work part-time in this industry” or “women can’t work part-time and manage a family” is wrong. Women are the best multi-taskers, because we have to be.

A number of my female friends have gone through that process – they were given quite menial tasks because other people feared they weren’t able to complete a full project. This is a tragedy not just for women, but for the industry – losing capability and talent.

Taylor Cullity Lethlean's Canberra Arboretum. Image: John Gollings.

Adelaide's Riverbank Bridge precinct, as realised by Howard. Image: Jack Baldwin

Towers Road Residence, TCL. Image: John Gollings.

The new Arboretum sits on an area earmarked for an arboretum in the original plan for Canberra that was never built. Image: John Gollings.

So we’ve developed a flexible work policy in the office now, and we have a couple of people who are working part-time. We’ve been making sure that we actually give them proper project work to do, because that’s why people join the design industry – they don’t want to be put on the shelf to do paperwork or admin. Design inherently is sporadic in nature, so that means you’ve got to have a methodical planning method to manage part-time staffing, but it really comes down to making sure that employees and employers are flexible on both sides.

FG: AILA’s national president, Linda Corkery, talks about the “expectations of production” within the design industries that seem to burn people out. Whether it’s the all-nighter, or the unrelenting hustle associated with student life, do you find that continues in the professional sphere?

LH: The practice workload ebbs and flows, and that’s one of the hardest things in our industry, because we don’t get a consistent amount of work. You can’t spread things out daily, monthly, or yearly because it doesn’t work that way.

There are always pressure points whether it’s competitions, submissions or final deadlines. There’s a constant engagement with work that makes it difficult to switch off – particularly with the devices we have now. These pressures impact both men and women, but as society evolves to a more shared understanding of parenting, there’s no reason these barriers should be particular to women in the industry.

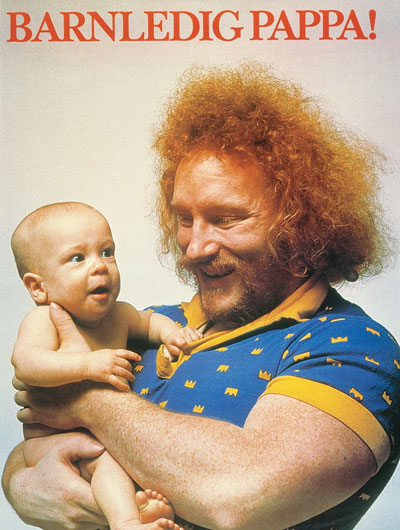

Swedish parents are offered up to 480 days of paid parental leave. From the ’70s the Försäkringskassan (the Swedish Social Insurance Agency) encouraged fathers to increase their parental leave. In 2018, Swedish fathers take up three months of paternity leave. By contrast, data from the Australian Bureau of Statistics still shows that Australian men have been slow to take up any kind of flexible work arrangement around childbirth.

FG: Given that you’re on the younger end of the spectrum when it comes to being a practice director, do you feel that you bring different perspectives to the way you see work?

LH: I hope so. I believe in working smarter over just working longer. The approach I apply is that I’d rather work really hard during the day to get out of here on time. It’s something that I try to instil in my staff as well. We all know that working long hours means you’re not functioning properly anymore, so you need to know when to call it.

I do recognise that there’s a shift in my generation related to the relationship between genders. I don’t find that men are constantly needing to prove that they’re dominating over women. We’re peers, we’ve gone through the same studies, and all opinions are valid. You’re also starting to find that young fathers are taking extra days off to ensure that their partner can do work part-time, or just have some time-off.

FG: What kind of structural changes do you think the landscape architecture profession needs to make to become a kinder place for women?

LH: I think our fellow industries have a bit of a role to play in this, because it should feel more like a partnership. When you line up the statistics, you’ll find a lot more skilled female landscape architects than their peers in architecture. So structural change is about how industry-wide gender equality relates to architecture, construction or engineering.

What our industry can do is to continue to support its female leaders and see whether or not there are other things we can do. Whether it’s mentoring programs or industry talks similar to what Parlour does, this signals to others that we’re all working together to actively promote women in design, in order to give hope to younger female landscape architects. I think we need to value the skills and thought diversity that our women bring to the industry – shape our working culture, so it supports flexible work practices, and ensure that women are valued, respected and engaged with as equals.

––

Lisa Howard is TCL’s fifth director, appointed in January 2018. Previous projects include the Riverbank Pedestrian Bridge, Adelaide; Brisbane Airport Link, Queensland; Shanghai 2010 Expo Australia pavilion, China; and Eastern Precinct and Forum Landscapes, Monash University. In 2017 Howard was a finalist in the Women’s Agenda Emerging Leaders Awards.