Why does Australian landscape architecture have a gender problem?

Evidence points to significant pay disparities between women and men in landscape architecture. To better understand the issue, the Australian Institute of Landscape Architects is launching a new gender equity study in collaboration with Parlour and Monash University’s XYX Lab.

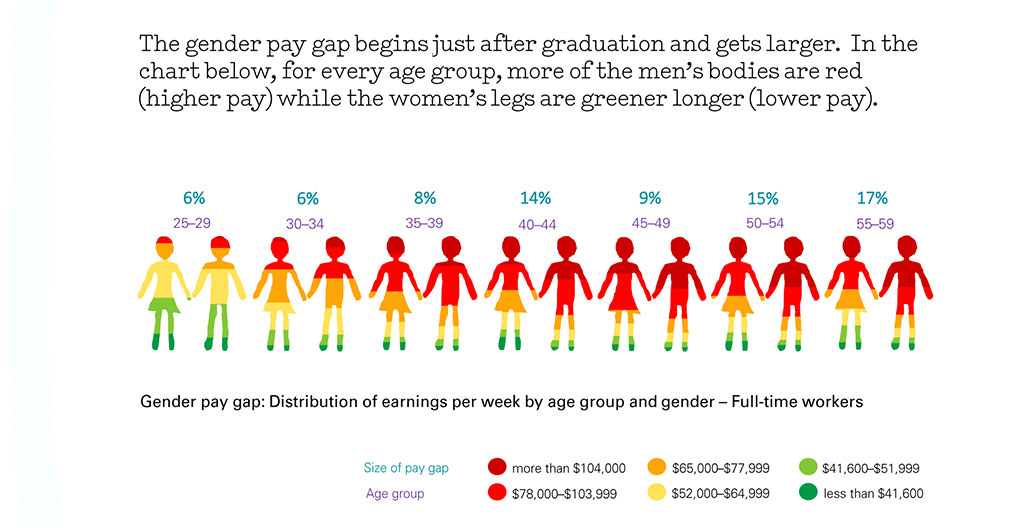

In honour of International Women’s Day, a sizeable portion of Australia’s attention this week has been focused on the achievements of women, from celebrations at the Opera House to the ABC. Of course, a week such as this also highlights the grave disparities that remain between men and women in Australian society, most especially in its workplaces. Australian Bureau of Statistics data tells us that the average full-time male worker earns roughly 15 percent more than the average full-time female worker in any given week – and while this gender pay gap varies across industries, it is always present, and women are always worse off than their male counterparts.

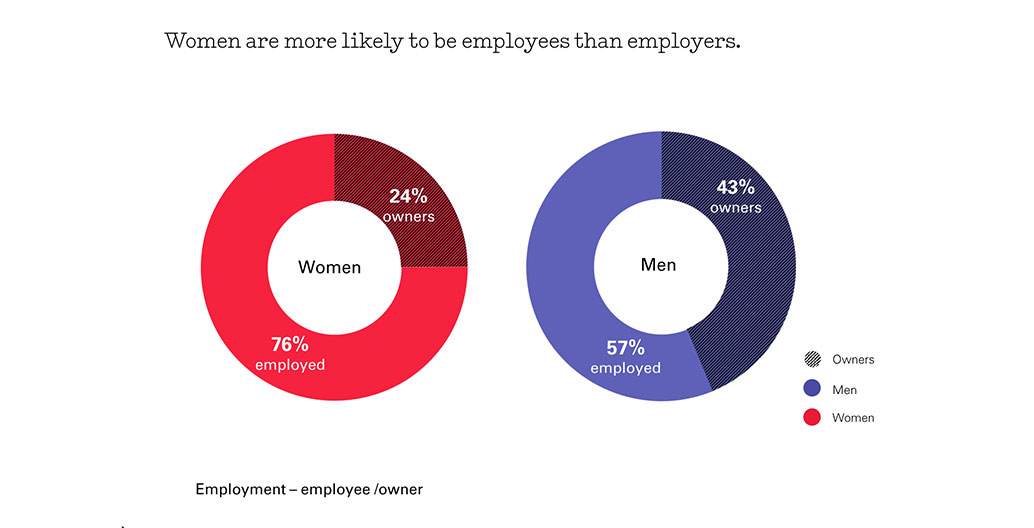

Recent evidence suggests the landscape architecture profession is no different in this regard. In 2017 the Australian Institute of Landscape Architects (AILA) conducted a survey of its members’ salaries, and of the survey respondents, women represented 70 percent of the lower paid positions, while men represented 100 percent of the high-income positions Like so many other spheres of Australian working life, gender disparities abound in landscape architecture, leaving women more financially vulnerable and with less opportunities for career development.

One person who has bucked the trend is Lisa Howard, director of Taylor Cullity Lethlean (TCL). Aged 36, she is one of the youngest female practice directors in the industry, holding senior positions within the practice in the years leading up to her directorship.

“We’ve been really lucky here at TCL. I’ve never experienced any gendered assumptions about the types of things I can do, or assumptions about my work because I’m a woman. But certain assumptions have become more noticeable as I’ve progressed in my career outside of the office,” Howard says. “When I’ve arrived on some sites with a junior male colleague, the guys on site automatically assume that he’s my senior and direct questions to him. It’s only when we’re walking around and I’m answering the questions that they realise I know more about the project.”

When she first began her working life, Howard felt a dissonance between her experience at university and the industry: “As you get out you realise that the majority of design directors are male, even though there’s a lot of gender parity between graduates. So you’re seeing that a lot of men are rising up, but hopefully it’s just a generational thing,” she says.

Since AILA’s inception in 1967, only 14 percent of National Presidents have been women. Its current incumbent, Linda Corkery, is the fourth woman to take on the role.

Linda Corkery is the current AILA National President. Image: UNSW Built Environment

“I came to Australia at the time when Catherine Bull was AILA’s National President, and since her tenure ended in 1985 there’s only been one other woman who’s been the national president before me,” says Corkery. “There’s a saying that ‘you can’t be it unless you see it’. Right now, we’ve got about a 50-50 gender split in the membership of AILA, so seeing women succeed in our industry is very important.”

Questions about participation are a lot more vexed when women have broken into traditionally ‘male’ domains. In the design industries, Corkery recognises that women face “a different type of pressure”, whether they’re in the boardroom or on a construction site.

“There are preconceived ideas about what a woman does, if she knows what she’s doing, her physical strength, or what she looks like on-site. That’s a big thing for women and more often than not they’re the odd one out. They’re constantly in a situation of having to prove themselves,” Corkery says. “As a young practitioner, I found that the big thing for me was getting my voice heard – that was as much to do with being young as it was with being a woman. You just assume you’re on an equal footing, but that’s not necessarily the case.”

The data confirms the experiences of both Howard and Corkery, with gender disparities occurring across generations and across all Australian industries. The Australian Human Rights Commission has found that women on average take home $283.20 less than men each week, despite making up roughly 46 percent of all employees in Australia. Meanwhile, women still spend twice as much time looking after children under 15 compared to men, with previous research finding that average superannuation payouts for women equated to just over half (57 percent) of a man’s payout.

“Contrary to the evidence available, you find that young people think gender disparity is not really a problem, it’s something that’s hit older generations… but when they age they start to feel it, as they start seeing that women are simply disappearing around them,” says Dr Gill Matthewson, architect and lecturer at Monash Art Design and Architecture (MADA).

Matthewson is a seasoned researcher on the question of gender within the design industries. Her PhD, Dimensions of Gender: women’s careers in the Australian architecture profession, translated anecdotal appearances into evidence, sourcing hard data that was then furthered in a collaboration between Parlour and MADA’s XYX Lab, charting the experiences of gender in architecture. That model has informed a Gender Equity Study intended to audit women’s participation in landscape architecture, which AILA has just announced.

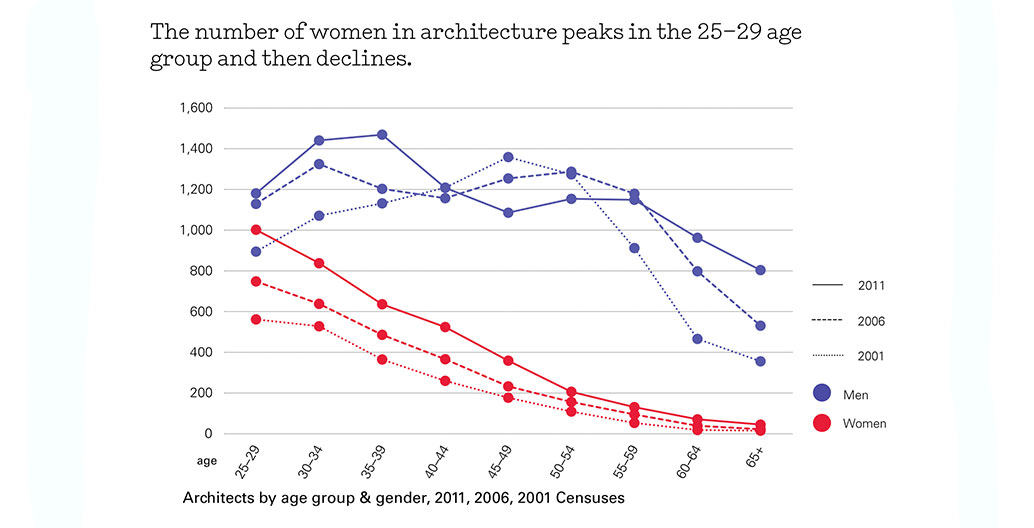

“Initially, what we’re going to look for is data about salaries and how women age and progress within landscape architecture,” says Matthewson. “We’re going to be pulling all of the data from the 2001, 2006, 2011 and 2016 censuses as it does count just about everybody. This means we’ll be able to identify what the overall gender patterns are within the industry.”

For Australian architecture, census data is confirming the anecdotal evidence of pay disparities for women in leadership positions, and in some circumstances, junior positions, too.

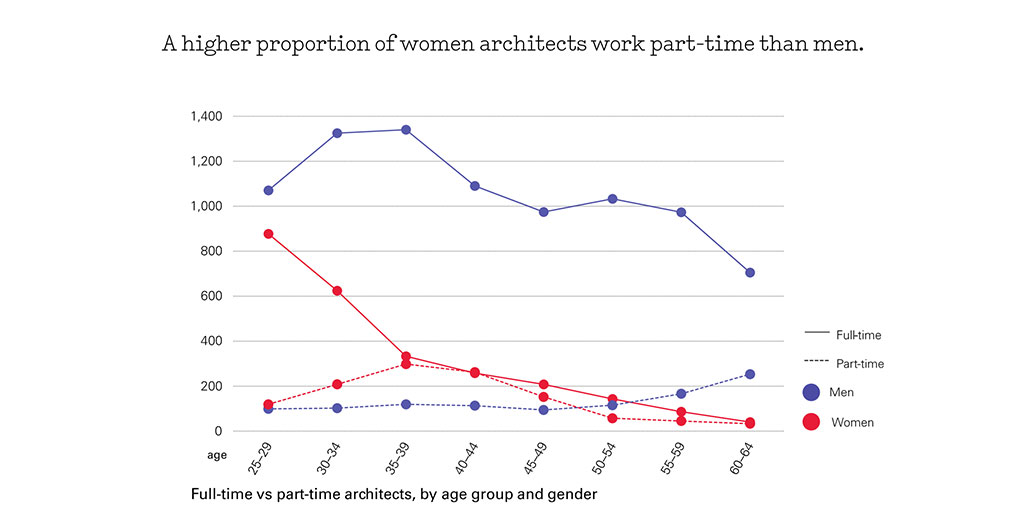

“At the moment we’re just finishing a report on similar census data for architecture that tells us that female participation is increasing, and of course that’s partly because they make up half of all graduates,” says Matthewson. “But as women age, more of them leave. So that creates some complexity about pay disparity in senior roles, because as there’s more older men in the profession, the data will reflect more men getting paid higher because of experience.”

Garnering this data allows all members to industry to see power imbalances clearly. Image: Parlour

In Australian architecture, prospects for gender pay parity never even begin. Image: Parlour

The reasons working part-time in architecture are complex, and these complexities are said to be reflected in landscape architecture. Image: Parlour

As with anecdotal evidence in the industry, more women leave as they age. Image: Parlour

Parlour’s initial report, The Numbers in a Nutshell, found that women make 44 percent of all architecture graduates, though only 22 percent progressed into being registered architects. Even if women made it into the latter group, they still make up the bulk of the junior ranks of the profession.

“The architectural profession does breed the idea that you have to be incredibly committed to it, which starts to create problems for women when they start having children – although it never seems to be a problem for men,” says Matthewson.

It is hoped that the Gender Equity Study will help the landscape architecture profession understand the contours and extent of the problem. While the first-phase of funding has been confirmed, AILA has called upon practices, local councils and other employers in the industry to donate to the study in order to complete, and accelerate, the research. For Corkery, financial investment from the industry will signal a unified push to address the issue industry-wide.

“We’re inviting practices to contribute to the cost of doing this study, which is also a way of getting buy-in to the idea from the profession itself,” says Corkery. “The decision to invest in this study validates gender disparity as an important issue for individuals and practices, which is something we can all get behind.”

Matthewson says the study will lay the framework for broader questions about what structural disadvantages exist within landscape architecture, and other design fields.

“When we opened up the numbers in architecture, that led us on to more things. The number of Indigenous architects in Australia was such an embarrassingly small number that the 2016 Census had to tweak it so that individuals couldn’t be identified. We’re also finding that young Asian men are typically cast into IT-heavy roles, despite their design talent,” says Matthewson.

“People need to be informed about the data on the ground in order to change the conversation – because gender disparity isn’t a problem that will simply go away.”

––

The Australian Institute of Landscape Architects invites all practices and individuals to donate to the Gender Equity Study.