Gutter journalism: Reflections on a quarter-century of Kerb

Kerb is a student-edited landscape architecture journal that has been produced by RMIT University for close to three decades. Five past and present editors convene to consider the steady contribution of this enduring publication to the discourse of landscape architecture and the city.

Kerb has come a long way since its inception in 1994 as a zine-like magazine launched by a group of landscape architecture students at RMIT University. Now, in its 28th edition, Kerb is one of the longest-running journals of its kind in the world.

Over the course of its history, it has served as a testbed for the critical explorations of a host of emerging Australian landscape architecture and city-making professionals. It has also consistently attracted incisive contributions from some of the world’s most respected design theorists and practitioners.

Former Kerb editor and Foreground’s editor-at-large, Jo Russell-Clarke led a discussion at the National Gallery of Victoria for Melbourne Design Week on the history and relevance of Kerb with three former editors, Cassandra Chilton (Rush Wright Associates, Hotham Street Ladies), Claire Martin (Oculus) and Ricky Ray Ricardo (Oculus, previously Landscape Australia), and one current editor, Alexander Maxwell-Anderson.

The full audio of that discussion can be found below, together with an edited version of the transcript.

Jo Russell-Clarke (JRC): To begin with, I just want to briefly read a bit of the editorial from the very first issue:

This inaugural issue of Kerb is a first in Australia, a journal of landscape architecture produced by undergraduate students. Kerb is a forum for the critique, discussion and redefinition of landscape architecture. It attempts to forge a link between the built reality and the unrealised possibility. The editors perceive such a publication as being essential to the development and enrichment of our profession in theory and practice. The agenda set in this issue of Kerb will be continued in subsequent issues.

Cassandra, you were there at the start and a student contributor to the first issue and were specially thanked in the editorial acknowledgments. Can you tell us, why did Kerb happen?

Cassandra Chilton (CC): Kerb was born out of a need for a forum for landscape architecture students to talk about ideas. Julian Raxworthy, who was the first editor, had this idea of starting our own magazine because we, as landscape students, could not get into other journals. They weren’t interested in what we had to say. Landscape architecture was seen as quite parochial. Julian gathered together a range of students and we went to Leon van Schaik and said, would you give us a thousand dollars to publish a journal of landscape architecture. And he did. It amazes me that it still exists given other student publications of the time are no longer.

JRC: That’s an interesting question for you, Ricky, from your perspective in publishing, how or why has Kerb survived?

Ricky Ray Ricardo (RRR): I think that the number one reason would be that it’s part of an institution that supports it and that is very proud of it. It’s possible to say that Kerb could have been a viable thing on its own back in the early 90s but circulation figures have dramatically faded since. Circulation numbers in the early 90s were higher than they were in 2010, 2012. So, Kerb wouldn’t have survived, I imagine, if it was an independently-owned publication.

But now, I think that we are at an interesting time where online media is booming. People are reading more, potentially less substantial writing as they may have, with our shortening attention spans and whatnot, but reading a lot.

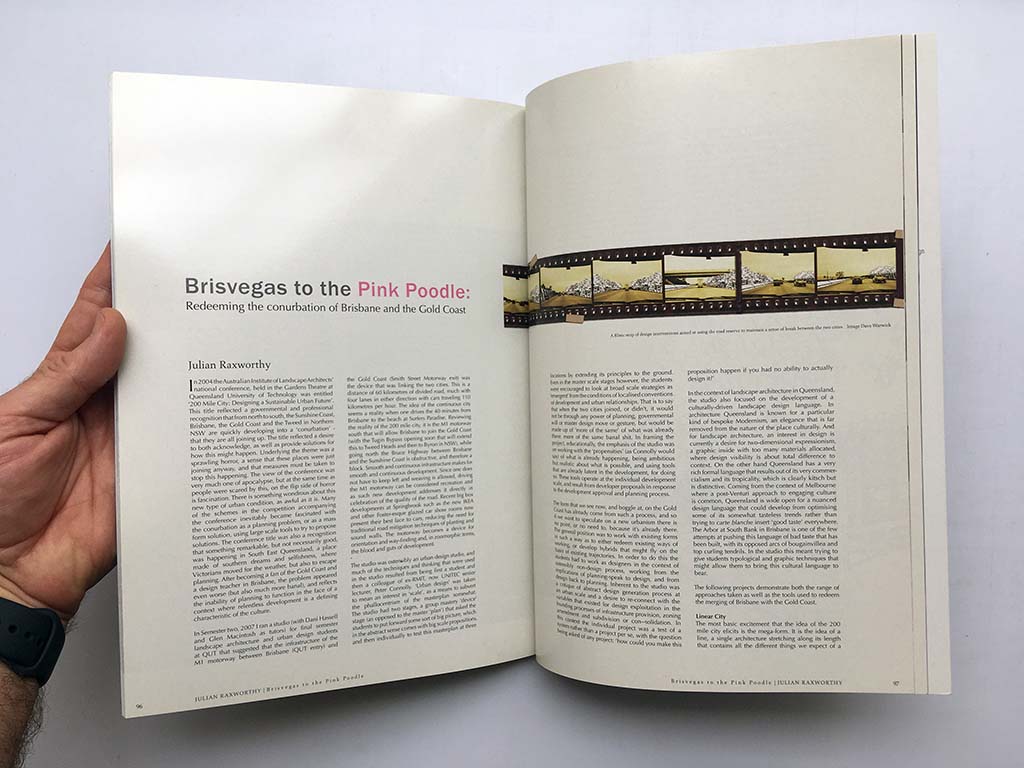

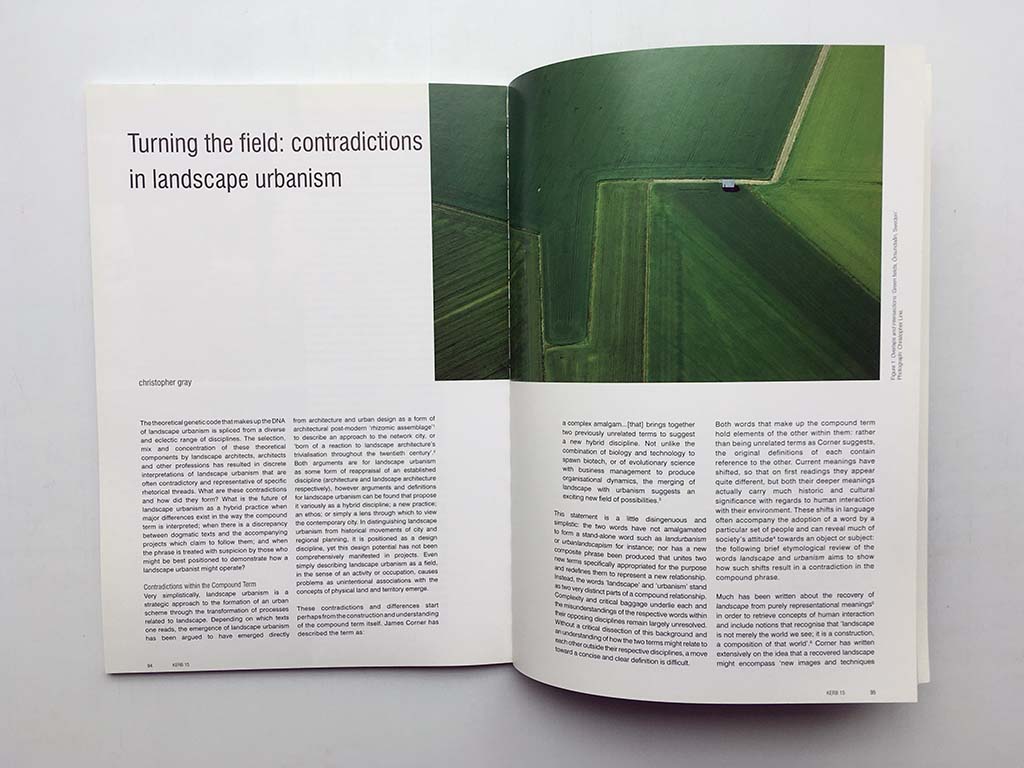

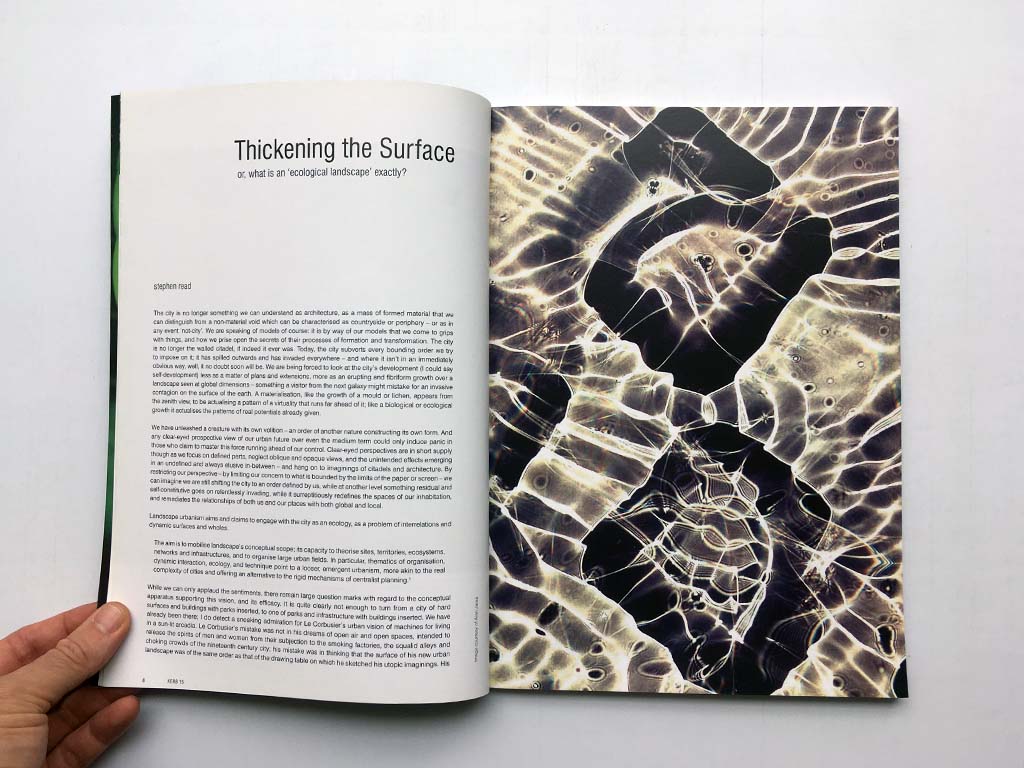

JRC: Claire, you were an editor of the 15th “international issue” – as it was proclaimed – of Kerb. You took a decidedly international theme ‘landscape urbanism’, which was just emerging and little known in Australia, and the editorial begins by quoting from the UN’s then new World Cities Report that we were entering a millennium of unknown mega-cities. So can you tell us a bit about why you chose this theme?

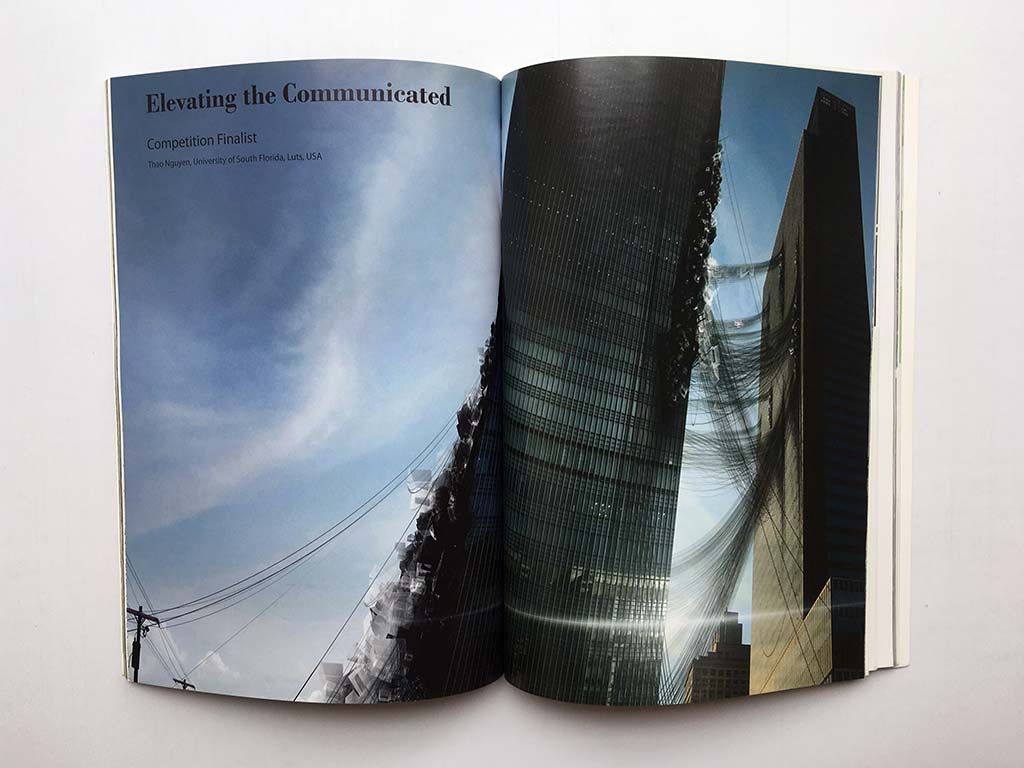

Claire Martin (CM): Landscape urbanism was definitely something that was being taught in the program at that time, whether it was through Peter Connolly’s take or other lenses. It was also a nod to what was still then quite a North American tradition and remained largely a North American tradition. I think it was a very deliberate strategy for us to choose something that was international. The look and feel of the journal is different too. It’s a bit less like a zine, with a jazzy cover and higher quality production, which were all a conscious effort. We also did things like promoted sales through Amazon, so we wanted to reach a global audience.

Something that we were interested in, and I remain interested in, is the perspective offered as landscape architects looking at the world. We weren’t necessarily going to be limited to our profession and who we spoke to or how we framed our edition was really beyond the discipline.

JRC: It does raise an interesting question, given it seems that landscape can be about any and everything. Have any of you struggled with what is appropriate content for a journal of landscape architecture? Have you refused submitted articles on the basis that they’re outside the scope?

RRR: Keeping in mind there is an expectation on Kerb as well – from former editors or other commentators – I think Kerb allows relative freedom in what we do look at, far more than if it was a professional publication. Something also to consider is, in Australia we don’t have many platforms for landscape architecture discourse. Kerb definitely provides the most freedom in pursuing whatever idea the editors deem relevant. But it does need to come back and connect to our own discipline.

CM: Adding to that, Australia does have Foreground and Landscape Australia plus Kerb and we have obviously digital and print versions of those publications. So I think actually Australia is overrepresented in the publications that we have in landscape architecture, which is actually a very good thing. I still agree though, in comparison to other design disciplines, we have many fewer opportunities to communicate to a broader public. So I think it’s good to acknowledge that, because I think it is about the strength of a culture that is bigger than the landscape architect population.

JRC: Cassandra, I wanted to ask you about ‘gutter’ because I know you had a chuckle at the title of today’s event. I suppose this comes back to speaking a little bit about student adventure and exploration.

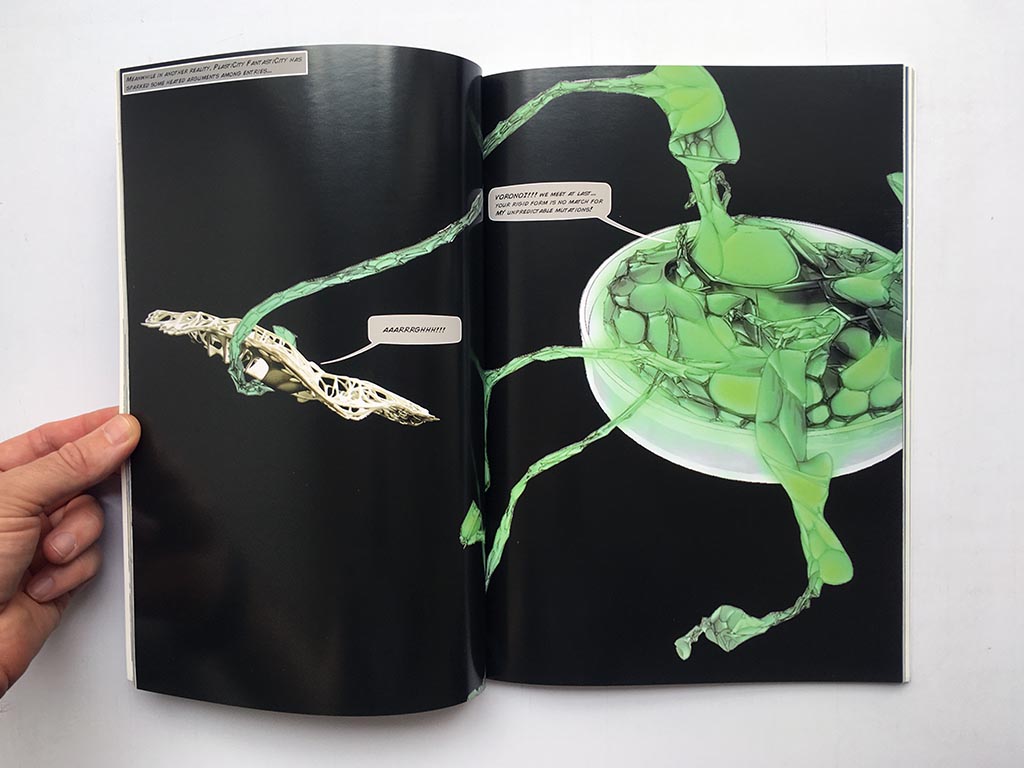

CC: One of the things that’s always interested me about Kerb is how it positions itself as a student journal. Does it actually see itself as a student journal? And what would be the benefit of that? Perhaps why I laughed was that by roughly issue five, it was felt that actually Kerb had become a bit mainstream in RMIT. And so a side group of people created a magazine called Gutter, which was a self-published, piss-take of Kerb and had their own opening and launch. And they were told by RMIT at the time not to release it. So I wonder, have we lost that questioning? Is Kerb radical enough anymore?

JRC: Alexander would you like to comment on that?

Alexander Maxwell-Anderson: I think we’ll just have to wait a see! Throughout our theme development, it was hard to focus on anything other than the state of crisis that the world is in right now. The theme for Kerb 28 is “Decentre: designing for coexistence in a time of crisis”, and that’s a really big and expansive topic that could include so much, so it’s really a question of where we draw the line on what content to include.

JRC: Kerb has obviously morphed into many things over its time and themes are common for issues of Kerb, but occasionally there weren’t themes. There was also diversity of media – cartoons, reviews of projects and written work. In more recent issues, has that diversity changed a little?

RRR: Kerb now exists in a global world, an internet world. So it’s less about documenting a local discourse and perhaps more focussed. Going back to Cassandra’s point, is it radical enough? I think Kerb can still be radical and tackle a theme, which is not to discount the charm of something zine-like and radical and fun when it’s all open-slather.

CC: I also see it as a question about a level of professionalism and what the aspiration of the journal is. It’s not saying one is better than the other but I think, to me, there’s a certain idea that now Kerb has to be super professional and not a student journal whereas it has been a place for students to be able to show things they couldn’t show in other forums.

CM: But it’s also in the context of education changing, isn’t it? We have a more privatised version of education so I think it’s not possible to separate out the two. When we did the 15th issue, some people were critical of it becoming almost more professional but that was a deliberate decision both by our panel but also by us. And I think we were three or four mature age students motivated to a degree by taking it to a different place. Whether that was right or wrong, it was a product of its context.

JRC: I wondered if you could name a few names that either of your own editions gave you access to. Of course, the third edition that was nominally launched in Barcelona was first the ‘international edition’, and had a very interesting international interview-springboard for its theme.

CC: That’s right. That is the issue that I co-edited, Kerb number three, and we interviewed Ignasi de Solà-Morales. So this is in 1996, just post the Barcelona Olympics and the whole issue was about terrain vague, which was very exciting at the time.

RRR: People want to speak to you when you’re editing a journal. It gives you amazing access. When I was editing Kerb in 2011, we were given media passes to attend the Australia Institute of Architects National Conference, which we would never have been otherwise able to afford. We spoke to Teresa Moller, Francois Roche, and few people we didn’t realise were names and have subsequently become names like Rachel Armstrong, and Dan Roosegaarde as well, who does amazing things with sense technology.

CM: We had a contribution from Charles Waldheim, who had written a very influential book on landscape urbanism. He did an interview with Moshen Mostafavi, who had also written on the topic. But then we also sort of stretched the thematics slightly by talking to people such as Kathryn Gustafson.

Having the opportunity to have those conversations was quite significant in the way it starts to reframe your own way of conceiving landscape architecture. But it’s also that as soon as you’re creating something, you are no longer on the periphery of the discourse. You can contribute to the discourse.

–

Kerb 27: Selection Perceptions – Who are we really designing for? is out now.

Expressions of interest are now open until the 18th of April 2020 for Kerb 28 Decentre: Designing for coexistence in a time of crisis. Kerb journal is seeking submissions of abstracts for text and image based works, from landscape architecture and broadly associated fields, based on the theme.

Click here for more information and how to submit to issue 28.