Trains, planes and lawn mowers: Philip Coxall’s journey to landscape architecture

Foreground brings you the second in a series of conversations with Anton James. Here he talks to the straight shootin’ Philip Coxall of McGregor Coxall.

Anton James: Were you outdoors much as a kid?

Philip Coxall: No I wasn’t outdoors much. I was a city kid. I remember being interested in a Jacaranda tree at school because it flowered every now and then, but other than that, Auburn at that time was very much home to bitumen and concrete. When I was 16 my dad and I concreted the backyard. We did it because we didn’t want to mow the lawn and it make it a cricket pitch.

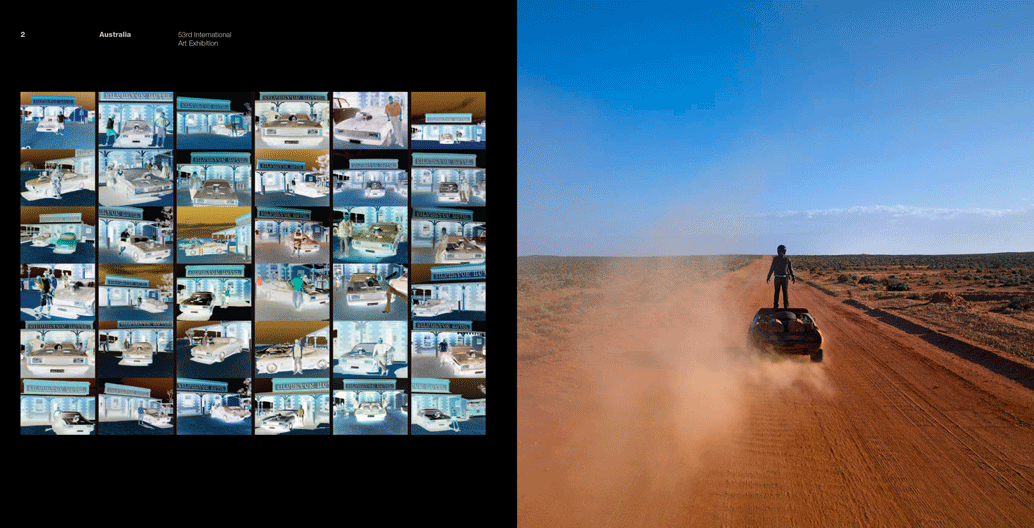

AJ: I’m interested in these different conceptions of what landscape could be. Some people talk about beauty in the landscape as if that’s a given, but then you could consider Shaun Gladwell’s 2009 work for the Venice Biennale. His thing is all about bicycles and cars and motorbikes. In one of his works he’s riding a bicycle across the headland at Clovelly beach, on all the sandstone boulders. So he sees that sandstone headland as an opportunity to do some skillful riding, whereas somebody else would see it as a romantic Sydney landscape.

Different people form different ideas about what a landscape should be. I am interested in when and where the idea of landscape as something with some agency is formed. Whether you understand it through the lens of property, conservation, ecology or just a space you need to have flat to play cricket, everybody has a landscape in their head.

Sean Gladwell 'MADDESTMAXIMVS' shown at the Australian Pavilion for the 2009 Venice Biennale.

Sean Gladwell 'MADDESTMAXIMVS' shown at the Australian Pavilion for the 2009 Venice Biennale.

Shaun Gladwell 'Interceptor Surf Sequence' (2009). Image via the Museum of Contemporary Art, Australia.

PC: I don’t even know how I got into it. When I first finished school I studied industrial design and worked for a local firm called Malleys, that manufactured fridges and washing machines. I wanted to design the washing machines, so I did an apprenticeship at TAFE to study this. But I remember coming back from the beach one day during the Christmas holidays, and there were these guys across the road building a garden for a new apartment complex. They were planting Nandina and Cordyline and all that. And I just looked at them out there, in their shorts and suntans, doing something, building gardens and thought, that can’t be half bad.

I told mum that night that I’d seen these guys doing this, and I wouldn’t mind doing that actually. We had a friend who was building landscape gardens, so she put me in contact with him and he told me about the Ryde School of Horticulture. At the time I didn’t know a bloody plant, but all of a sudden two weeks later I’m sitting in a class with blokes in boots and shorts and t-shirts, you know, dirty as all shit because they’d come from a day at work doing TAFE.

Then one day I was flipping through the library at Ryde and I came across the sand gardens of Ryoan-ji in Japan. The Japanese landscape book I was looking at had all the beautiful little gardens of Japan and then all of a sudden that sand garden came up. I looked and I thought what a load of crap. But I loved all the other gardens. Then after I’d finished three years, probably right at the very end of my course, I was in the same library looking for the same book and saw this garden and it was like somebody had hit me in the heart.

AJ: The same one again?

PC: The same one again, but I just thought “Oh my God that is just stunning”. What happened! You’re brought up in the suburbs and you don’t appreciate beauty, or you don’t have that physical understanding of beauty. Then at some point I was ready to appreciate it. I just had to go to Japan. I had to travel there to see this.

AJ: That’s still a long way from landscape design isn’t it?

PC: It is. But it’s the starting point to understand space. And I suppose in a way, to understand Ryoan-ji is to understand the wider spatial arrangement of landscape and using the imagination to take you places.

AJ: So tell me about your move to Canberra University – what did they see landscape being at that time?

PC: It took me a few years before I actually decided to do it, but it was always sitting there. When I got to Canberra I had read Glen Wilson’s Landscaping with Australian Plants. Glen was one of the first people to actually focus on using Australian natives. He came up with these great ideas about putting three tube stocks in a hole so they get this twist. I never even thought like this. So I was interested in that kind of thing already.

If I got anything out of studying in Canberra, I’d say there were two important things: firstly, we studied with architects and interior designers and it was under a system where they were all kind of integrated. That taught me the important lesson of design not being isolated, but potentially part of the whole. Secondly, I remember an important crit with James Weirick. You know how you wait around for the crit, and you’ve got your stuff drawn and you’re waiting as the guy floats around and you get five minutes. James finally came up to me right at the very end. I’d been doing a design for a national park type walkway, but there was an information centre and I’d drawn it like “ye olde worlde” Australia vernacular. He walks up and he says, “If I see another building like that I’m going to puke,” and he walked off. It was a really crystal clear moment, because it made me realise that we’re not only looking at beautiful little curvy paths, but looking at everything, and that we have to challenge everything. James was a great influence.

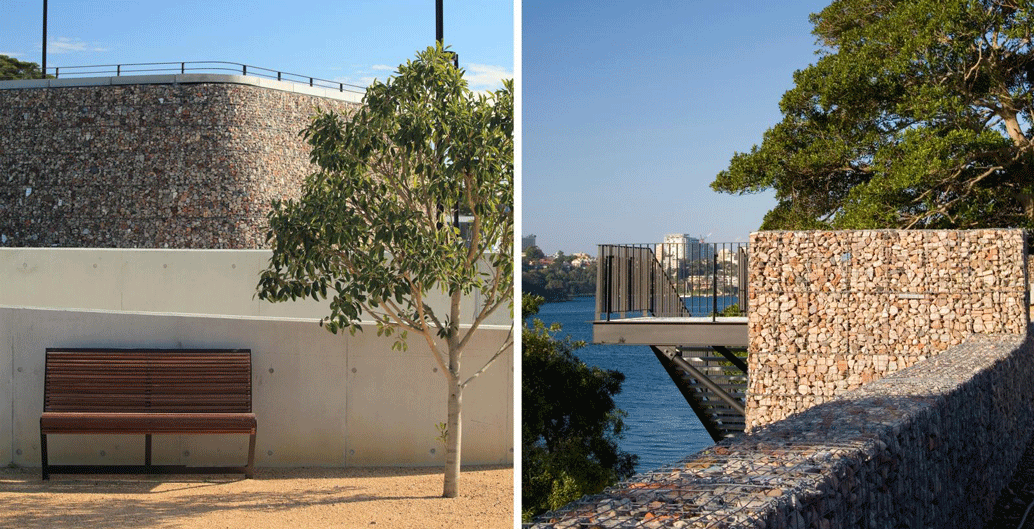

The lines of the MGC's Ballast Point Park.

A view from Ballast Point Park.

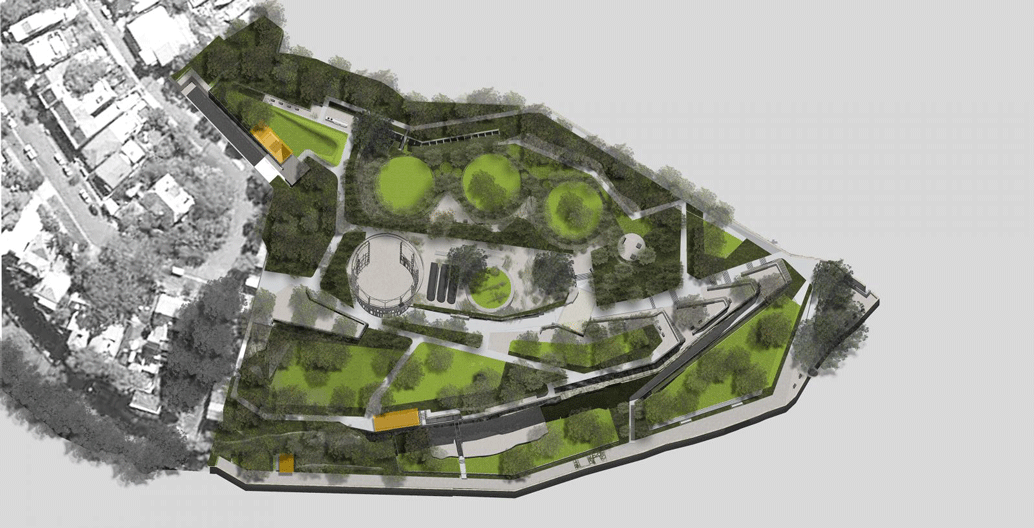

An aerial view of Ballast Point Park.

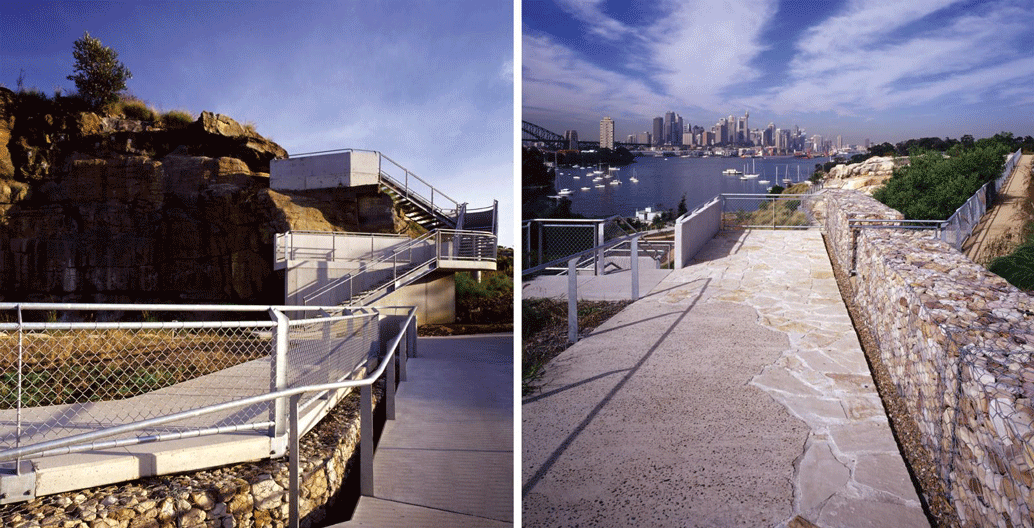

Ballast Point Park.

Ballast Point Park.

Ballast Point Park.

Ballast Point Park.

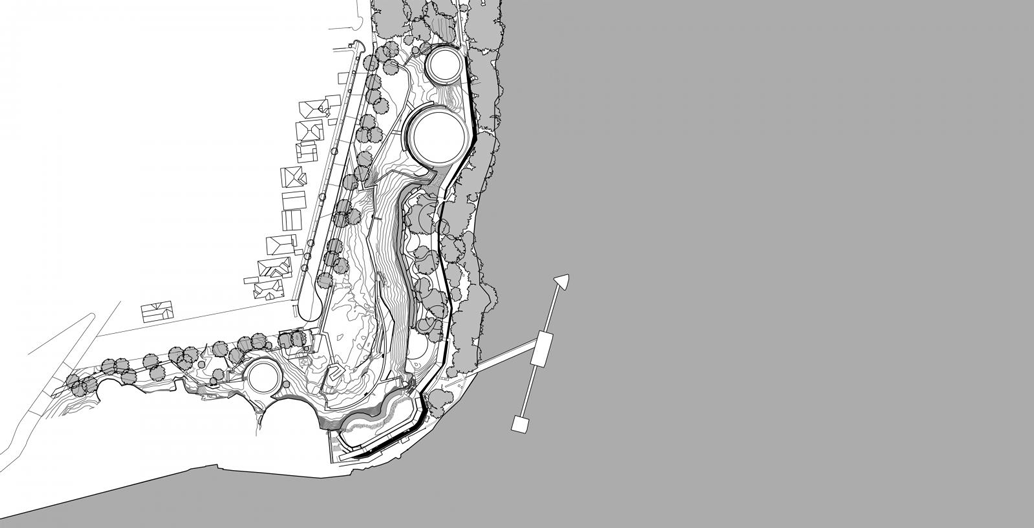

MGC's Former BP site park, Waverton, Sydney.

Former BP site park, Waverton, Sydney.

Former BP site park, Waverton, Sydney.

Former BP site park, Waverton, Sydney.

Former BP site park, Waverton, Sydney.

Former BP site park, Waverton, Sydney.

AJ: And then you went to Hong Kong after that didn’t you?

PC: Yeah. Hong Kong at that time was an incredible place, because it was just before the handover so they were spending all the coffers that the British had acquired before they handed it over to the Chinese, so they didn’t have to give them any money. They built the airport, they built the rail and they built all the new towns. So basically here I was, tossed in to doing all that.

AJ: Was it mainly that urban scale?

PC: Yeah, huge. I worked on the airport. I mean huge scale stuff. There was no real design philosophy but the beauty of Hong Kong was the opportunity to explore design, get it built, see how you messed up, and do it again and again and again and again. They were taking my drawings off the drawing board and physically building it the next dayAt that time I wanted to be a look-at-me designer. I wanted to be a punk landscape architect. I wanted to do stuff that people went “wow, check it out.”

The work was all run by the engineering, and while they had to have a layer of landscape, they essentially didn’t care. So they didn’t challenge me on anything. Then, I would go out to look at the projects, thinking “this is going to blow peoples minds,” and I’d look at it and just think “this is shit”. Then I started to realise that what I was after was simplicity and a sense of strong form and shapes, not timeless necessarily, but not voguish.

I worked on the whole airport, and seriously nobody challenged me, except for the pink and red runways. I’d just go for it. Then came all the train stations all the way along the new towns. Then work would come across from China because it was opening up. On Friday afternoon they wanted a marina designed for Zhangzhou or wherever, and they needed it by Tuesday. So you’d have to work fast.

An aerial view of Hong Kong International Airport. Image: Wylkie Chan.

Hong Kong International Airport's midfield concourse. Image: Hong Kong International Airport

Ryoan-ji gardens in Kyoto, Japan. Image: Cquest.

AJ: How was that then, bringing that experience back to Australia?

PC: When I left Hong Kong after the seven years I decided I was going to give up and get a mowing run. I thought I don’t want to do the thinking anymore. I just lost it all, that old belief. So I set up a mowing business and just got the ute, drove around and mowed lawns for two years. Then Adrian called me up one day and said do you want to have a go at this design competition (the one you won for Mount Penang Gardens), and after two years it was kind of the right thing to do.

AJ: Do you think you brought that Hong Kong landscape mindset or had you always the different view in the back pocket?

PC: What I brought was all the fuck ups that I’d made, and I’d learned from. But also, I brought my European connection through my wife. For example, I was always fascinated seeing in Germany how they’d use raw galvalised metal. It was simple and raw. I definitely brought that kind of material understanding to our work. I was always fascinated with materials. In Hong Kong, if you get the material wrong it will be destroyed so quickly because of usage, because of the weather and the climate there.

AJ: Looking at Ballast Point, that level of detail could be traced back to your industrial design past couldn’t it?

PC: It could be. I know that I’ve always been fascinated with the idea of something being used for something else. For example, I took a train out to a site visit out past Green Square one day, and I got off at the wrong train station. There was nothing there, as they were just starting the development. But there were gabion walls, built as a temporary measure, where they’d trucked in all the broken concrete from a wall that they’d demolished. I looked at that and I just thought that’s actually quite interesting. Then when Ballast Point came around, those buildings were being knocked down and then being chucked away – and then all of a sudden there’s an idea of how to reuse it.

AJ: Do you think the practice has a particular ethos about what landscape is?

PC: I have always been fascinated with the idea that we are part of nature. We can look at a beaver build a dam or at a termite nest, and be amazed at what they’ve done. I think the same about us. I can’t look at anything that we’ve built and say it’s not natural. We mightn’t like everything that’s built, we mightn’t think it’s beautiful, but Adrian and I are interested in this idea of the city being an organism. If you talk about reusing materials, reusing water, reusing whatever – it’s a system. Then the question becomes, how can you work into the system?

––

This is an edited excerpt from a conversation between Anton James and Philip Coxall for the landscape architecture podcast, Landscape Conversations. Subscribe to the podcast here.