Writing the Australian landscape

Australia’s landscape has always loomed large in the country’s literature. From Tim Winton to Georgia Blain, the island continent has made for great reading – and a recent poetry collection from the award-winning poet Mark Tredinnick continues in this fine tradition.

From Banjo Patterson’s romantic portraits of Australiana, to the evocative NSW hinterland of the late Georgia Blain, Australian landscapes have always loomed large in our stories. With this in mind, a recent collaboration between landscape architecture practice Taylor Cullity Lethlean (TCL) and the award-winning Australian poet Mark Treddinick represents a natural alignment of interests.

“We coalesced very seamlessly because TCL has been interested in the poetics of landscape, and of the Australian landscape in particular,” says Kate Cullity, director at TCL. “Mark’s abstraction of language, or reducing of language to its essence, mirrors our approach to landscape. It acts as a metaphor of the human condition.”

The practice and the poet came together as part of TCL’s Expanded Field of Landscape Architecture Creative in Residence program – a one-off project grant of $9000 awarded to anyone within a ‘creative’ discipline. Administered by the Kevin Taylor Legacy, a fund launched in memory of the practice’s late director (and occasional poet), the grant aims to bolster TCL’s engagement with broader creative disciplines, and in turn inform new approaches to TCL projects.

“As a landscape architecture practice we’ve always been interested in collaborating with people from other disciplines,” says Cullity. “By doing this we expand the possibilities of our projects, because we can bring people who think laterally to create new ground.”

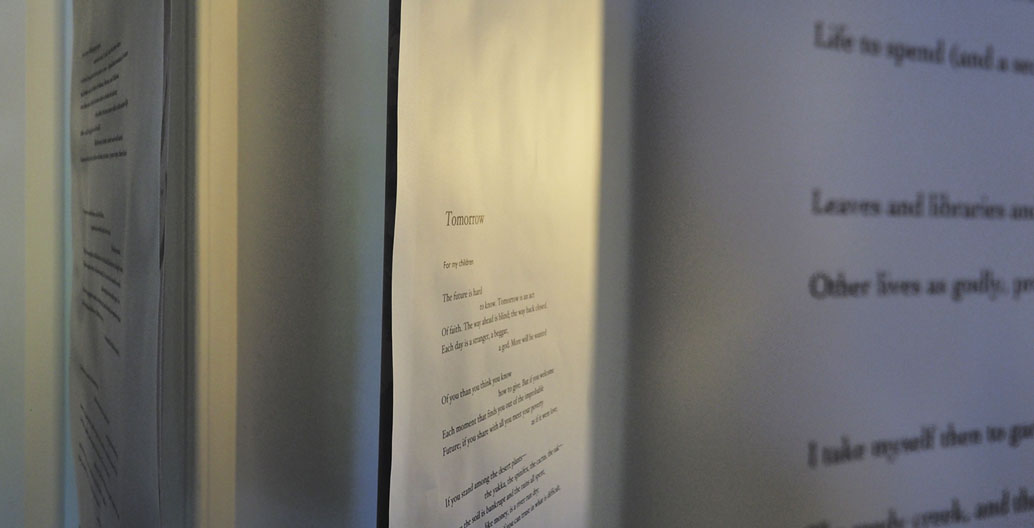

‘Tomorrow’, a poem by Mark Tredinnick on exhibition at TCL. Image: Tony Kearney.

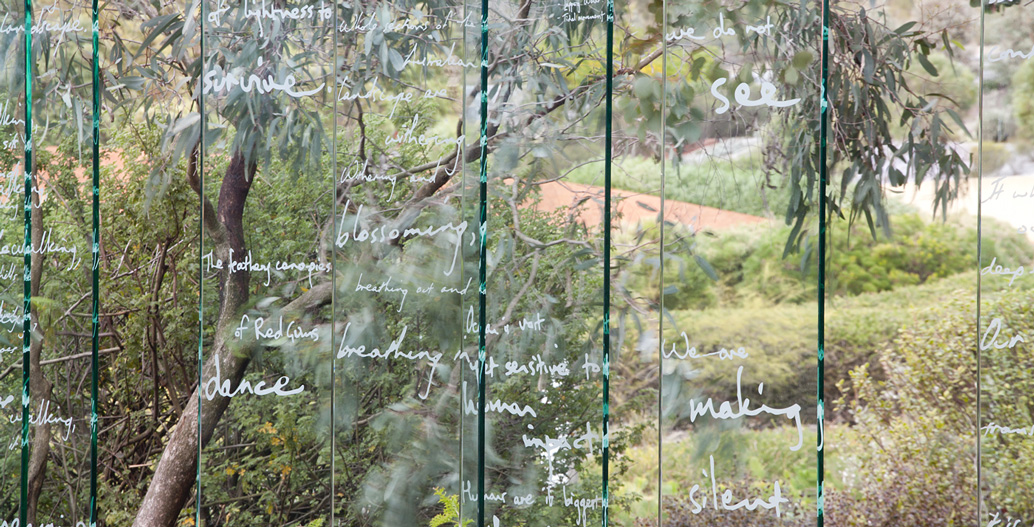

TCL's exhibition of Mark Tredinnick's poems produced during the residency. Image: Tony Kearney.

Mark Tredinnick. Image: Tony Kearney.

But the decision to participate in the residency didn’t come as naturally to Tredinnick (despite both his father and grandfather being gardeners). “To some extent I’ve written against the garden,” says Tredinnick. “Reflecting back on my initial judgements – which in retrospect, are very narrow – I cast gardening as something where the individual exerted too much anthropocentrism, or in other words, putting something somewhere it didn’t want to be.”

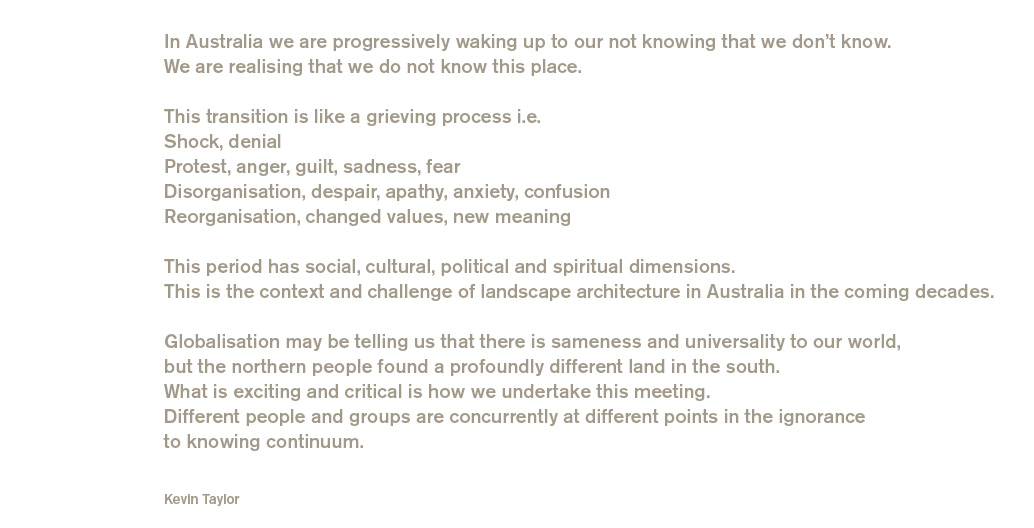

Over millennia, human hands have sculpted the landscape, and through colonial expansion, introduced conceptions of ‘tending’ the landscape have had a dramatic impact on countless indigenous landscapes and cultures. In Australia, this attitude underwrote the country’s settlement by Europeans from its conception, with the fallacy of terra nullius fuelling settler domination of the continent. The psychological effects of this history span generations, as noted by Australian writer, George Seddon, who has been an important influence on both Cullity and Tredinnick:

“They (the English) have not in general been sensitive to new cultures and the indigenous environment … They are our ancestors and we owe much to their energy, but it has sometimes been blind, and we are still learning to see our own land and to forgive it for not being England” – Swan River Landscapes (1970).

Indeed, the gulf between indigenous and non-indigenous landscapes is sometimes glaringly obvious – in Melbourne, for example, the city’s traditionally European tree canopy has buckled under the Southern Australian drought. So, given the historical baggage of Australian landscape interventions, what compelled Tredinnick to follow through with the residency?

“The process forced me to re-examine my ideas and I found them wanting,” says Tredinnick. “In responding to a brief about gardens, I still wanted to avoid imposing my judgements about them. In a sense it’s giving a landscape agency, which in turn allows someone to become more themselves by opening up and allowing the place to take you in.”

TCL’s current design development for the Bendigo Botanic Garden’s Garden for the Future formed the stage for Tredinnick’s re-appraisal of the garden, culminating in a suite of ten poems presented with a series of creative responses to the poems from TCL staff, including drawings and artworks. That garden is due for completion in 2018, with Tredinnick’s poems inserted into the landscape.

“The garden itself has a new kind of aspirational statement imbued in it,” says Tredinnick. “Bendigo’s early wealth was about ripping stuff out of the ground and ruining the soil that was there. This garden responds to the consequences of that, and replaces gold with green.”

The late Kevin Taylor.

Kevin Taylor's poetry (1).

Kevin Taylor's poetry (2).

“It’s our human desire to want to modify and mould the landscape,” says Cullity. “We have been cultivating the landscape for millennia – and throughout that we’ve always brought something different to it given our social and cultural contexts.”

This collaboration between Tredinnick and TCL has been an act of landscape cultivation. While working within the confines of the residency’s landscape-driven remit, what’s resulted is a cultural exchange that otherwise breaks the silos of two seemingly distant creative practices.

“We’re very interested in the idea of distilling or abstracting the landscape, rather than recreating a more elemental landscape or just copying something from another time,” says Cullity. “As landscape architects, we’re interested in mining the land for meaning which mirrors poetry, because both forms ask what needs to be distilled.”

—

The Kevin Taylor Legacy is currently open for applications to the 2018 Expanded Field of Landscape Architecture Creative in Residence. TCL will soon be launching a chapbook publishing the work generated from Mark Tredinnick’s 2016 residency.