Venus and the Pleiades: A reflection on women in landscape architecture

Almost seven years ago, landscape architect Hilary Hamnett reflected on her career and the influential yet understated history of some key women in the profession. Delivered as part of Adelaide’s ‘Women with a Plan’ forum, Hamnett offers a deeply felt message for International Women’s Day.

It’s not an original observation, but everyone’s career develops along a unique professional path, with all sorts of factors influencing it to turn in one direction or another. My path has perhaps been one of what I would call presence rather than prominence in the design professions, and in particular landscape architecture. However, it’s the balance of the two and the importance of both that I would like to focus on, illustrating this with women who have affected our lives, practice or vision either by more overt prominence or, less obviously, by more covert actions and presence.

Landscape architect Hilary Hamnett FAILA

I studied Landscape Architecture in the UK in the early 1970s. At that time two of the most prominent people in the profession were Dame Sylvia Crowe and Brenda Colvin, CBE, both women who pioneered the practice of 20th century British landscape design. Both were also instrumental in establishing the British Institute of Landscape Architects in 1929 (now called the Landscape Institute). Brenda Colvin, the now less well remembered of the two, was not only its first woman president but the first woman president of any environmental or engineering professional institute.

These two inspiring and visionary women, directly influenced at least two generations of design professionals, and indirectly continue to influence anyone who engages with the places that they designed. Both were forerunners in designing large-scale industrial landscapes and Brenda Colvin, in particular, had a natural affiliation with the new discipline of ecology, believing, with great foresight, that “land, water and air form the matrix of life on earth and landscape is the form in which we see them”. She studied and used naturally occurring plant communities as a foundation for her work. Brenda frequently did the planting designs for the third most prominent landscape architect of the time, Geoffrey Jellicoe, as he would boast that he didn’t know any plants at all. Many subtexts can be inferred from that.

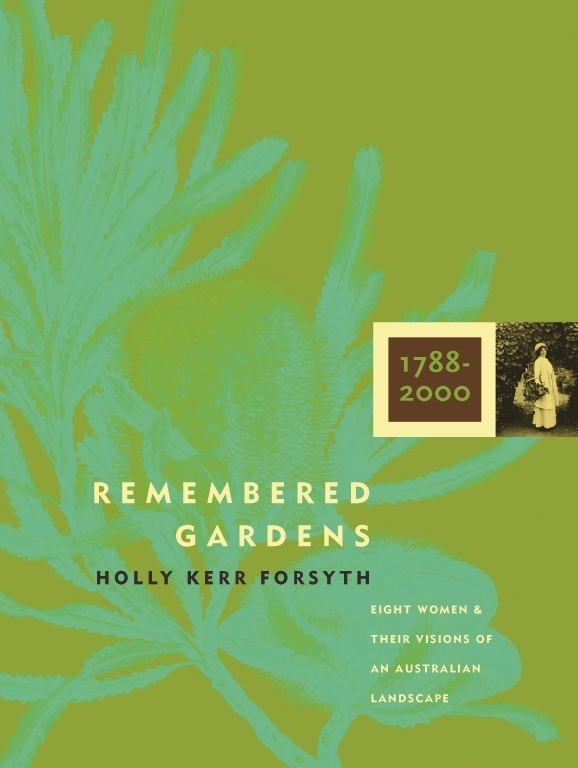

I now want to jump from the beginning of my career as a landscape architect to as recently as last Sunday – Mother’s Day. I was given a copy of Remembered Gardens by Holly Kerr Forsyth, who people may know from her columns in the Weekend Australian. The book explores the work and stories of eight women from 1788 to 2000 whose passions for garden making have shaped our relationship with the Australian landscape. It begins with Elizabeth Macarthur, and her experience coming from the rich, romantic tradition of the English landscape to the harsh realities of early colonial Australia; moves on to a chapter, as one might expect, on Edna Walling – another remarkable and highly influential woman – and ends with Kath Carr whose life, like that of Sylvia Crowe and Brenda Colvin, spanned the 20th century.

‘Ironbark and Tree Everlasting or Dogwood’ (1947). Image: Edna Walling Collection, SLV.

![‘East Point. Terrace. Looking to [L]aghton[?]’ (1947). Image: Edna Walling Collection, SLV.](https://www.foreground.com.au/app/uploads/2017/10/703219291.jpg)

‘East Point. Terrace. Looking to [L]aghton[?]’ (1947). Image: Edna Walling Collection, SLV.

‘Our first dining room with the A.W.A.S. against a rock’ (1947). Image: Edna Walling Collection, SLV.

‘The man who came to dinner (kookaburra)’ (1947). Image: Edna Walling Collection, State Library of Victoria.

‘At the end of the little track running off beyond the terrace, through the trees we looked down at Grassy Creek’ (1947). Image: SLV.

And we must mention Kath Carr. Who is Kath Carr you may well ask. Until opening Remembered Gardens I, like many people, had never heard of her. She wrote very little, hardly ever drew plans and her notebooks, sketches, correspondence and treasured books and papers were disposed of when she moved into a retirement home.

But as a disciple of Edna Walling, Carr nevertheless evolved an independent “vision of what an Australian garden could be”. She drew inspiration from the natural landscape and worked with the available materials and plants that emerged from and survived in the local climate to express each individual place. She never repeated her designs from one commission to the next, and always drew fundamentally from the unique context of each project.

Kerr Forsyth writes that, through her reticence, Carr is not widely known but lives on through the memories of her clients, the notebooks that she encouraged them to keep, and the enduring qualities of the properties and gardens she created.

Another aspect contributing to the lack of awareness of Kath Carr is the intangible, understated and ethereal nature of the designs, making it difficult to put a precise definition on how or why the landscapes work. This quality is something that occurs not only in landscape and other areas of design but many of the creative arts such as writing and music. In literature it has been referred to as the clear pane of glass through which new ideas are effortlessly transmitted. When we meet with barriers as a result of careless, thoughtless or poor design we become frustrated and defiant; where intensive thought, research and refinement has removed these barriers and pared the design back to its apparently simple but effective form the hand of the designer becomes, effectively, invisible.

This invisibility can be frustrating, but influence by stealth is something that many women, especially, encounter or employ in their work to achieve a result.

‘Remembered Gardens’ by Holly Kerr Forsyth tells the stories of eight Australian garden designers.

As an example, my first job after graduating from the Landscape Architecture programme was with the newly created Rijnmond Planning Authority in Rotterdam in the Netherlands. I was working with State Planning designers and public artists on a large scale regional recreation project and had to attend regular meetings with the design team, elected members and representatives of the Nature Conservation Association. It seemed to me essential that I learnt Dutch, even though most people in The Netherlands speak excellent English. But to be able to follow the discussions, I insisted that they only spoke to me in Dutch, which was quite a struggle at first but I think paid off in the end.

At one meeting there was a long discussion about how the work was to be tendered and, without going into too much detail, I managed to get a word in and suggest that it was done under two separate contracts for two stages. The suggestion was passed over pretty quickly and the discussion continued back and forth for some time. As the meeting was drawing to a close one of the engineers suggested that the works were tendered as two separate packages – and everyone was amazed, and thought what an excellent idea, if only they had thought of it earlier.

Maybe it was my Dutch, but it was not the last time that I’ve had this type of experience, especially where I have been the only woman in the room. On another occasion, having carefully considered the layout of a caravan park for a private owner operator, the client took one dismissive look at the plan and said “my 8 year old could have drawn that”. I would love to have sat down with the 8 year old and seen what they came up with. Perhaps the client was right, but not, I think, in the way he intended.

Viewed in conjunction with a crescent moon, Venus has a spellbinding dynamism and tension. Photo: NASA/Bill Dunford

As individual designers, we need to recognise that there are many different strategies for influencing and contributing to our professions, and diversity, along with a bit of self esteem, are what we should strive for. We need prominent leaders who can inspire and attract others both within and outside the profession, who can promote our professions through senior management positions and good use of media as well as through their work. But at the same time, the variety of life experiences we bring, and the less obvious, incremental changes made by working as individuals or in collaboration, are every bit as important. It is vital to sow the seeds of ideas where and when we can.

The planet Venus is often visible in the western evening sky and, when viewed in conjunction with a crescent moon, has a dynamism and tension that I, at least, find quite spellbinding. Venus is the second brightest natural object in the night sky and so dazzling, in fact, that it can cast faint shadows. Last month, as it does every eight years, Venus passed directly in front of the constellation of the Pleiades, or Seven Sisters. This cluster of young stars is so elusive that it is barely visible with the naked eye, yet it has been the source of countless myths and legends and the basis for cultural practices across the blue planet. One commentator of this recent event, Dr Tony Phillips from NASA, said “When Venus joins them in conjunction, it will look like a supernova has gone off inside the cluster. Strangely, though, the Pleiades do not look puny in comparison, just delicately beautiful.”

I think it’s a wonderful analogy for our various roles as women in the design professions (and elsewhere too) even to the extent that each is enhanced by its relationship to other bodies.

–

Hilary Hamnett is a Fellow of the Australian Institute of Landscape Architects and Principal of Hilary Hamnett & Associates. She lives in Adelaide.