Troppo troppo

The tropics in Australian literature runs the gamut, from bountiful home of an ‘amiable and extrovert race’, to a place steeped in slavery and indigenous suffering. Author Suzanne Falkiner traces the lineaments of an Australian tropical literature, forever tinged with uneasiness.

As for verandahs. Well, their evocation of the raised tent flap gives the game away completely. They are a formal confession that you are just one step up from nomads.

The people living in the Australian tropics have always tended to make a virtue of their difference, seeing themselves as less conformist and more insouciant than their southern neighbours. More than one writer of the region has used the region’s distinctive architecture as a metaphor.

‘Houses perched on stilts like teetering swamp birds, held stiff skirts all round, pulled a hat brim low over the eyes; and with the inroads of white-ants not only teetered but eventually flew away. And then, we tend to build houses so that we can live underneath them. Perhaps those stilts made southerners think of us as bayside-dwelling Papuans. Our dress, too has always been more casual. Our manners indifferent, laconic….’ wrote Thea Astley in 1976, in a lecture entitled ‘Being a Queenslander: a Form of Literary and Geographical Conceit’.

Despite cultivation of a laidback air, the relationship between the newcomers and the landscape has always been tinged with uneasiness. The poet Les Murray got the sense of fragility and impermanence right in his poem ‘Louvres’ in 1984:

In the banana zone, in the poinciana tropics

Reality is stacked on handsbreadth shelving,

Open and shut, it is ruled across with lines

As in a gleaming gritty exercise book.The world is seen through a cranked or levered

Weatherboarding of explosive glass

Angled floor-to-ceiling. Horizons which metre

The dazzling outdoors into green-edged couplets.In the louvred latitudes

children fly to sleep in triplanes and

cool nights are eerie with retracting flaps.

The louvred glass can always be exploded by a cyclonic wind; the weatherboard, consumed by rot and endless damp, similarly dispersed. The tropical regions of Australia were the last that the British settlers made their own. Their foothold was initially precarious, and historically the two were hostile to each other.

But just as the first imported wooden buildings were frangible, so also was corporeal European society susceptible to destruction, when transplanted to those latitudes, whether to heat, cyclones, mosquitos, fever, grog, or Aboriginal spears. With no resistance to tropical diseases such as malaria and dysentery, the crews of early visiting ships were often decimated. In return, the sailors and settlers introduced alcohol and venereal diseases to the local populations.

The nation’s northernmost tropical settlement, Darwin,or Palmerston, as it was until 1911,was destroyed three times in its short history. After the failure of a shifting string of settlements in the early 19th century which were attempted largely to thwart any ambitions the French might have had in the region, a port was permanently established in 1869.

Initial British interactions with the local inhabitants were undeniably brutal, going a long way to justifying the description of the colonists as invaders rather than settlers. Even later, as the history of the northern pearling and pearl shell industry demonstrated, atrocities continued: Aboriginal women kidnapped as divers and concubines were cruelly treated, and sometimes thrown overboard and drowned to avoid retribution by the authorities. The settlements themselves were largely built on Chinese labour, followed in Darwin by hardier Mediterranean races such as the Greeks.

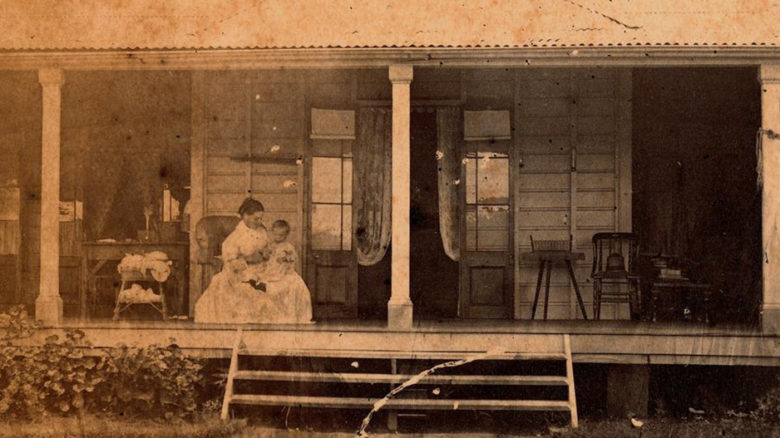

Edmund Rawson's veranda in 'the hollow'.

An early 'investigation' into early labour practices in Queensland

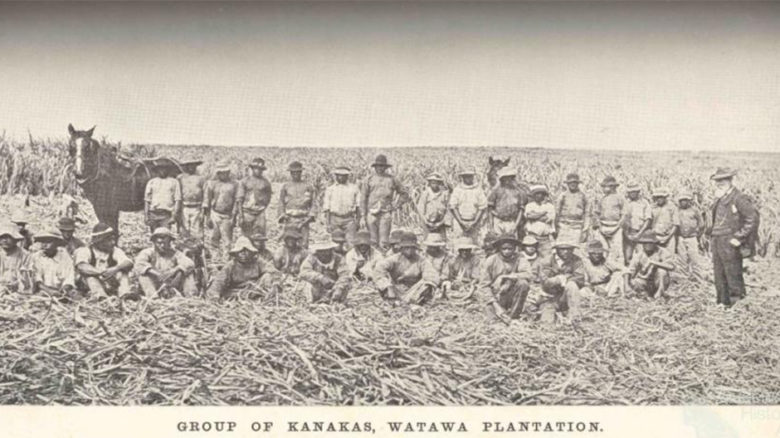

'Kanakas' or Melanesian indentured labourers were the backbone of early settlement in the top end.

'Kanakas' or Melanesian indentured labourers were the backbone of early settlement in the top end.

This was an environment hardly conducive to great literature. Most early accounts were non-fiction reports composed by visiting government officials, travel writers and journalists. Banjo Paterson, passing through briefly, thought the ‘Northern Territory of South Australia’ best left alone. ‘The Northern Territory has “broke” everybody that ever touched it in any shape or form, and it will break Britain if she meddles with it’, he wrote in the Bulletin in 1898, before going on to describe the Asian population who provided the workforce in highly racist terms. Palmerston was supported by pearlers, the mines, and Government officials, he noted, while white employment was restricted to staffing the offices of Overland Telegraph (‘the O.T. men’) and of a ‘little tin-pot railway’ down to Pine Creek. These, along with a publican or two, the Government Resident (always referred to as ‘the G.R.’), some lawyers, a doctor, a few storekeepers and customs officials, and a buffalo shooter, pretty well made up the white population, he considered. Paterson continues:

Palmerston is unique among Australian towns, inasmuch as it is filled with the boilings over of the great cauldron of Oriental humanity. Here comes the vagrant and shifting population of all the Eastern races. Here are gathered together Canton coolies, Japanese pearl divers, Malays, Manilamen, Portuguese from adjacent Timor, Cingalese, Zanzibar niggers looking for billets as stokers, frail (but not fair) damsels from Kobe; all sorts and conditions of men.

Kipling tells what befell the man who ‘tried to hustle the East’, but the man who tried to hustle Palmerston would get a knife in him quick and lively. The Chow and the Jap and the Malay consider themselves quite as good as any alleged white man. … There is an Eastern flavour over every-thing; when the Palmerstonians want to gamble at the annual races they do it by Calcutta sweeps, an Eastern form of betting little known or practised elsewhere in Australia.

Ernestine Hill, half a century later, concurred. Darwin had just two classes of people, ‘those paid to stay there and those with no money to go’, she wrote in 1951.

On the whole, it would not be until the 20th century that the northern outposts would find their true chroniclers. These later writers, unlike some of those that came before, would not always overlook the darker side of their history. It was only with the arrival of Xavier Herbert’s massive novel Capricornia in 1938, that the sufferings and injustices inflicted on an Aboriginal population, and others then voiceless in the European cultural sphere, were documented.

In Queensland the first such tropical outpost, Brisbane, was established at Moreton Bay in 1824 as the colony’s third penal settlement. This development, on a site known to the local Turrbal people as Meanjin, was welcomed neither by the Aborigines nor the convicts sent there. The settlement’s third governor, Patrick Logan, notorious for his harshness, was killed either by Aborigines or convicts, or possibly one with the encouragement of the other, an event brought to life in Jessica Anderson’s often-neglected novel The Commandant, from 1975.

The climate there was similarly hot, wet, and fecund, and the British were again convinced that Europeans, or rather, Englishmen, could not work there. This time the sugar industry relied on exploited ‘Kanaka’ or Islander labour, in an indenture system often based on kidnapping and near slavery. The Italians, Greeks and Maltese who were encouraged to come and work on the sugar farms, were also not quite counted as ‘Europeans’, it seemed.

By 1961, however, Patrick White found Brisbane ‘full of interesting ramshackle houses built on stilts’ and inhabited by a people who, when met on the street, seemed ‘an amiable and extrovert race.’ But it would be left to novelists Astley and David Malouf — in Johnno (1975), and his memoir Twelve Edmondstone Street (1985) — to celebrate the city’s distinctive architecture and people.

However, in an era of accelerating climate change, and of the descendants of those British settlers careless attitude to it, perhaps one should leave the last word to Randolph Stow, writing in 1979, who admittedly was thinking of Australia’s old colonial possession, Papua New Guinea (Visitants 1979):

“All right,” he said, “if you know so much, have you ever heard of a piece of music marked troppo agitato?”

“I don’t think it’s possible,” I said.

“I think it is. I want to hear it. At the end, all the instruments would be in bits.”

“I’ll bet it’s been done,” I said.

“Ah, but this would be tropical,” he said. “I can see it,” he said. “The glue would melt in the heat, and the wood would warp, and the strings would rot away with damp and snap, one after the other. The brass would turn green, and mildew would be growing out of the woodwinds. When it was finished, the instruments would be thrown in a heap, and they’d begin to sprout and turn into the trees they were made from. And reeds and vines, and the wind would blow through them and the birds would come. That part I’d mark finito, or troppo troppo.”

–

Suzanne Falkiner is the author of The Writers’ Landscape: Wilderness and Settlement, 1992, and Mick: A Life of Randolph Stow, 2016.