The things we keep: Why Australia must protect its national heritage

Buildings, parks and places form the cultural roots of Australian society, writes David Yencken AO. In this extract from his new book, Yencken calls for a redoubling of efforts to protect our national heritage.

What is the National Estate and why should we preserve it?

A country’s heritage is central to the connections its people have with their land and culture. It shapes their sense of identity, binds them together in inexplicable ways, and is often evoked by seemingly trivial things. My father, a diplomat, was posted to Spain as British Minister just before the outbreak of World War II. During this time, my mother travelled from Madrid to Barcelona to help greet a shipload of repatriated prisoners of war. She took with her sprigs of eucalyptus to give to the Australians among the allied exchange prisoners. She later told me that many of them burst into tears when they touched and smelt the gum leaves, so evocative were their distinctive feel, smell and look.

The historian Graeme Davison has suggested that my mother possibly shed a tear or two herself at these meetings, such is the pull of the Australian landscape for expatriate Australians. I too grew up with constant reminders of the Australian landscape, since my parents had Elioth Gruner and Harold Herbert landscape paintings hanging on the walls of their houses wherever my father was posted. These were not trivial influences, since Gruner won the Wynne Prize for Australian landscape painting no less than seven times, and Joseph Brown, famous collector of Australian paintings, pestered me constantly later in my life to sell him the Harold Herbert watercolour; it apparently had important associations for him too.

There are both tangible and intangible components of our heritage. The intangible elements include our folklore — the habits handed down by our families and friends – and our way of seeing and responding to the land. Our heritage also includes our written history, our musical traditions, our visual and dramatic arts, our literature, our political and legal culture, our patterns of community relationships, and our sporting traditions. Objects reflecting our natural and cultural history are some of the tangible parts of our heritage, but it is places of all kinds: grand natural areas, delicate ecosystems, terrestrial and marine environments, prehistoric sites, places of cultural significance to Indigenous people, historic buildings and structures, our finest gardens — in sum, Australia’s National Estate – which people most strongly identify as their distinctive heritage. While all other aspects of our national heritage should be regularly in our minds, it is on the National Estate that this book concentrates.

Gough Whitlam first used the term ‘national estate’ in a speech in 1970, asserting that ‘the Australian Government should see itself as the curator not the liquidator of the national estate’. Race Mathews, one of Whitlam’s advisers, took the term from one of President John F Kennedy’s New Frontier speeches in 1960. In turn, Kennedy’s speechwriters seem to have borrowed it from Clough Williams-Ellis, an eccentric Welsh environmentalist and architect. The Committee of Inquiry into the National Estate, established by Whitlam in 1973, described it as ‘a brilliant compression of much in little’. Eric Reece, then premier of Tasmania, described the term even more succinctly as ‘things that you keep’.

It expressed a fresh concept that cultural and environmental heritage should be looked at together. This was a novel idea in heritage practice around the world, and a valuable extension of heritage thinking, since heritage conservation is best seen as a continuum from wilderness areas least affected by man to structures and objects with little direct relationship to nature. Along that continuum there is no obvious demarcation line that might conclusively justify separating a natural area with little human intrusion from a modified landscape. Both might be equally beautiful and both might include pockets of vegetation or habitats of ecological significance. Very many national parks in Australia include structures or features of cultural significance and are the richer for it. Today it is recognised that Australia’s National Estate ranges from great areas of World Heritage standing, through to cave and rock art, and the smallest cottages and gardens. As the Committee of Inquiry into the National Estate noted, ‘the idea of the National Estate is most easily grasped as one all embracing concept and most effectively promoted by one body’.

Australia's Great Barrier Reef is the world's largest coral reef. In 1981 it was the first coral ecosystem to receive world heritage status. Photo: Wise Hok Wail

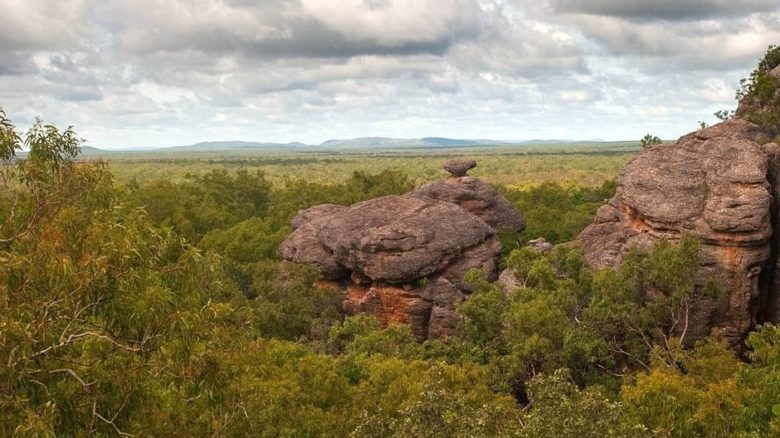

First added in 1981, Kakadu is dual-listed on the UNESCO World Heritage List for its outstanding natural and cultural values. Photo: pixculture

Uluru-Kata Tjuta National Park was first inscribed on the World Heritage list in 1987 for exceptional natural beauty. In 1994, it was the second park in the world to also be acclaimed as cultural landscape. Photo: mapu

Why should we preserve the National Estate? The most scientifically valuable and the most beautiful natural areas must be preserved for future generations and the world as outstanding examples of Australia’s environment. Representative examples of each of our various ecosystems and associations of plant species should also be preserved. They should include landforms and soils, plant communities and the breeding grounds and the habitats of all endemic fauna. The preservation of genetic diversity must be ensured for the health and stability of ecosystems, the maintenance of essential life support systems, the sustainable use of living resources and the ecosystems in which they are found, and the untapped and as yet unknown agricultural, pharmacological, industrial and other potentials of natural materials. Our finest natural areas should be preserved for the recreational, aesthetic and spiritual satisfactions they offer us. Many human designed or affected landscapes should be preserved for their beauty and interest and for the enjoyment they provide for people.

The most ancient archaeological sites provide vital evidence of the emergence of modern humans and of the colonisation of the Australian continent by Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples more than 50,000 years ago. Archaeological sites emphasise the richness of early Aboriginal society in Australia and its significance compared to other centres of early human development. Aboriginal rock engravings and paintings supply fascinating evidence of Aboriginal cultural values and creativity. They also provide records of Aboriginal perceptions of early foreign contact, including interactions with Macassan praus and European explorers and colonists. Contact sites where Aboriginal and white people met are not only of historical interest; some, such as massacre sites, are of particular significance to our national story. Many Aboriginal places, especially those where traditional life has persisted, have sacred or other symbolic significance to Aboriginal people.

Historic areas, structures and places provide us with tangible evidence of Australia’s development over the last 250 years. They are the cultural roots of today’s society. Historic places include both the artistic achievements of other times and examples of structures and places that are typical of regional life and work in Australia. Historic buildings, structures and places from other eras provide us with a diversity of building forms that give character and charm to our cities and countryside. Once destroyed, they can never be replaced.

Budj Bim (Mt Eccles) Cultural Landscape, located in the traditional Country of the Gunditjmara Aboriginal people was inscribed on UNESCO's World Heritage List in July 2019

Lord Howe Island supports a number of endangered endemic species. In 2007 the Lord Howe Island Group was added to the National Heritage. Photo: David Stanley

Flinders Chase National Park on Kangaroo Island, South Australia includes five state heritage places. Photo: Bernard Gagnon

To some people, the concept of the National Estate may seem abstract and remote, but for each of us there is some place, group of buildings, piece of country or natural bushland that is familiar, treasured and dear. Some groups such as our first Australians have special attachment to country. All of us look forward to enjoying some aspects of our national estate with our children and grandchildren. Sometimes the significance of the place is only recognised when it has been damaged or destroyed. This is the decisive personal reason why every Australian should have a concern for the conservation of Australia’s National Estate. Finally, the National Estate has a priceless economic value; protecting it should not be seen as a burden on the economy, nor a restraint on development. The National Estate is a precious economic asset as a tourist attraction, as the untapped gene pool for new pharmacological and other resources and much more. A final powerful statement expressed in the Committee of Inquiry report is that even if all other arguments are put to one side, the supreme justification for conservation of the National Estate is the deep feeling of most Australians that their descendants have the right to at least as many options in the cultural and natural environment as they have enjoyed themselves.

These arguments might be summarised as the need for biological, cultural and intellectual continuity. To provide that continuity, a national heritage regime requires strong leadership, effective legislation and appropriate funding, backed by state and local initiatives. These guiding principles should inform the interpretation of Australia’s past national heritage performance, any assessment of our current policies and the direction of future practice. The protection of Australia’s national estate, will not take place without constant vigilance. It is the shared responsibility of all those who care. In telling the story of national heritage regimes from the first established in 1975 until that in force today, I hope the book will empower all those committed to the significance of our national estate to redouble their efforts to protect it.

–

This is an excerpt – Chapter One – from David Yencken’s new book Valuing Australia’s National Heritage (2019) published by Future Leaders.

The book is free and can be obtained by sending an email to helen@futureleaders.com.au

David Yencken AO is Professor Emeritus at the University of Melbourne. He was Chair of the Interim Committee on the National Estate and inaugural Chair of the Australian Heritage Commission for six years. He was also the first Chair of Australia ICOMOS (International Council on Monuments and Sites).