The square and the park: a festival review

Michael Smith reveals curatorial richness in the 2019 International Festival of Landscape Architecture staged in Melbourne this month by the Australian Institute of Landscape Architects.

The Square and the Park. In recent times these two civic spaces have been the subject of intense debate in our society. Is it acceptable to lose park for infrastructure? What is the role of commercial activity? What is the role of these spaces in a 21st century city that is subject to climate change? It is therefore very timely that the Australian Institute of Landscape Architects took this to be the theme of their 2019 International Festival of Landscape Architecture. Held at the controversial Federation Square, this conference was an opportunity to unpack the role Landscape Architects play as designers of public space and influencers of the public realm.

The Festival was held over two days and was fabulously curated by Cassandra Chilton (Rush Wright and Associates) Jillian Walliss (University of Melbourne) and Kirsten Bauer (ASPECT Studios).

The Keynotes

The first keynote speaker of the festival was Günther Vogt (Vogt Landscape) presenting a European perspective. In an address that acutely set the context of the festival, Vogt discussed the various drivers of public space and the changes occurring to landscapes in Europe today.

Like many places across the globe, Europe is rapidly urbanising, dramatically changing both rural and city environments. In rural areas, cultural histories are at threat of being lost in the migration stampede for cities. Surprisingly this movement has led to an increase in forested areas as nature reclaims space abandoned by humans. This is in contrast to almost everywhere else on the planet which is seeing unprecedented levels of deforestation occurring.

In terms of the actors upon landscape, Vogt highlighted the rise in privatisation of landscapes as a key concern. Other key drivers include managing the impacts of climate change, the desire to control nature and the continued rise in mega-scale developments driven by urbanisation.

Against this backdrop, Vogt highlighted the need for Landscape Architects to talk more about the economy of landscape. As a key example of this, Australia has a choice in regards to coal mining and the Great Barrier Reef. In the long term we can really only have one or the other.

Julia Czerniac (Syracuse University) keynote address considered changing roles for parks at the square and the park festival in Melbourne. Photo: Jo Russell-Clarke

The square and the park festival co-director Kirsten Bauer speaks with keynote presenter Günther Vogt. Photo: David Hyde

Keynote presenter Kyung-Jin Zoh (Seoul National University) offered insights to very different Korean landscape development processes. Photo: David Hyde

Presenting a North American perspective was Julia Czerniak (Syracuse University). Beginning with perhaps the most famous park of all, Central Park in New York City, Czerniak noted that the purpose of urban parks has now changed. Parks are now about producing density rather than providing a relief from it. This connected strongly back to Vogt’s point about the need for Landscape Architects to discuss the economy of landscape.

Perhaps one of the most fascinating highlights of the entire festival was Czerniak’s presentation of the Seattle Central Seawall Project. This project was a major redesign of a public waterfront space that was to address sea level rise, reduce the risk of earthquakes on the sea wall, Re-establish a long-interrupted salmon migration route and create a high quality pedestrian space for the public.

In addition to being an extraordinary outcome, this project was also an exemplar of process. The public consultation process was a masterclass. Site tours, Outreach and tabling, public exhibitions with infographics and school engagement were all incorporated into the strategy. Czerniak explained that they didn’t ask the community ‘what do you want’, but instead ‘What do you know?’ This enabled the conversation to move into a vastly more useful knowledge driven process. Engagement with the local school was seen as a critical step in safeguarding the future success. It stands to reason that if the youngest in the community understand the project objectives and values, they will in time be better placed as custodians of it.

The final keynote speaker was Kyung-Jin Zoh (Seoul National University) Presenting an Asian perspective to the festival. Zoh’s presentation focussed upon the challenges of long term planning in shorter term political environments in the city of Seoul.

Like many cities across the region, the South Korean capital has been subject to very rapid change. The speed of development is obliterating traces of the past, leading to somewhat of an identity crisis. Rather than the city having layers of history preserved in built fabric, landmarks from previous eras are readily demolished to make way for the latest development.

The Debate

One of the big successes of the festival was in the curation. Rather than the simply pack the program with speakers and projects, considerable thought had been given to presenting and unpacking ideas in different ways. This was particularly evident through the inclusion of a debate on a hypothetical situation.

The year is 2020 and Federation Square had been completely destroyed by fire. The debate was presented as if it were a hearing to determine what the State should do in terms of a replacement for Federation Square, against the backdrop of a dire financial position. Should the space be sold off to be reimagined by private enterprise, or should it be rebuilt as a public square?

Speakers in the debate included Ricky Ricardo, Jillian Wallis, Claire Martin, Jacky Bowring, Mark Jacques, Tania Davidge, Kate Shaw and Sarah Bekessy.

A real positive out of this hypothetical was the ability to question and identify how design priorities have changed in a relatively short timeframe. Set against the climate emergency, would a hard paved square, with limited vegetation be an appropriate public space to design and construct today? In the view of many within the landscape architecture profession, the answer would be no.

The Comic Relief

A refreshing insight into the culture of the Landscape Architecture profession, came in the form of a light hearted critique of urban landscapes by Instagram celebrities ‘Shit Gardens’. Bede Brennan and James Hull, the creators of the ‘Shit Gardens’ phenomenon took the audience through a hilarious catalogue of detailing debacles, poor choices and flamboyant yet poorly executed intentions.

The ability for such a segment to occur at all, speaks volumes about the confidence of a profession that is willing to learn from mistakes, not just its successes.

The State of the Nation

Another excellent curatorial decision was in a series of presentations under the title ‘State of the Nation’. In these sessions thought leaders from each state across Australia were invited to speak about a critical piece of landscape architecture that was conceived in the 1990’s. The selected speakers were authorities on the subject work but not necessarily the authors of the work itself. This objectivity, combined with the very retrospective nature of the exercise enabled a brilliant critique of what had worked and what did not. The time frame also enabled reflections upon the issues and approaches of the day, compared with contemporary concerns.

The square and the park festival co-director Cassandra Chilton introduces The State of the Nation speakers. Photo: David Hyde

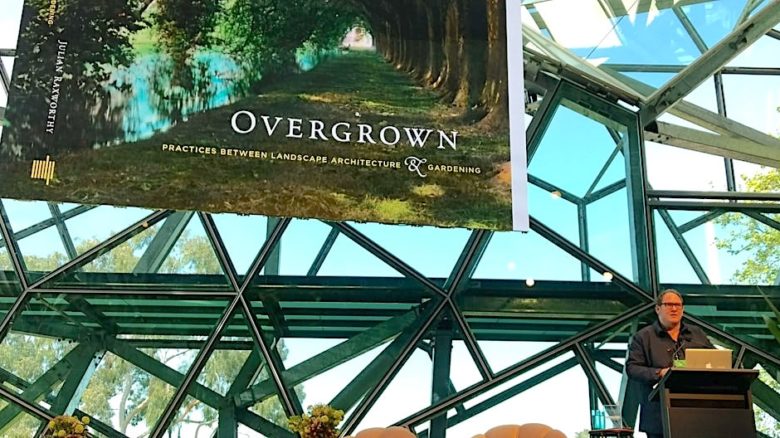

Julian Raxworthy speaks to the complex consideration of time in appreciation of landscapes, amply illustrated with the projects and ideas of his book 'Overgrown'. Photo: Jo Russell-Clarke

In 'The materiality of the square and the park' Mark Jaques, Jane Irwin and Huicheng Zhong offered varied and deeply considered thoughts on landscape material use. Photo: David Hyde

The Takeaways

Landscape Architecture is sometimes understood to be placed at the far end of the scale spectrum of our built environment. Landscapes are essentially the biggest physical thing humanity actually designs. Moving down that spectrum, as one zooms in on the scale, is architecture as the design of buildings. Given this proximity, one might assume architects and landscape architects deploy similar design approaches and are simply operating at different scales. From the perspective of an architect at a landscape architecture conference, it was curious to see how different these design approaches and indeed the design cultures appear to be.

A clear lesson for architects is to think more about their project in the context of time. At architecture conferences, finished projects are presented as they look on the day of completion. Rarely if ever is a project revisited decades later to determine the impact it had or the success or failures of the design. This ‘snapshot’ culture undoubtedly has flow on effects, such as buildings that are more difficult to maintain or adapt, and a reluctance to collect data for post occupancy evaluation.

The success of any professional conference resides in its ability to challenge perspectives and stimulate a rethinking of design. In this regard the 2019 International Festival of Landscape Architecture packed a significant punch. Sitting in the beautiful and somewhat uncomfortable seats at Federation Square, the question of what drives the design of our built environment, came into focus.

Is Architecture led by aesthetics and theory at the expense of data and post occupancy evaluation? Conversely is Landscape Architecture led by science and problem solving at the expense of theory and aesthetics? Julian Raxworthy claimed that Landscape was ‘under theorized’, whilst Julia Czerniak urged Landscape Architects to talk more about ‘form, beauty and pleasure’.

Perhaps there is a middle ground that both design professions are currently trying to move towards, from different sides.

Architects, Landscape Architects, Planners and Urban designers have a great deal they can learn from each other. In this regard perhaps what is really needed is for a regular Built Environments conference that would bring these professions together, every four or so years, in lieu of individual conferences and festivals in that year? What an opportunity that might present, in terms of learning from other perspectives and understanding different approaches. After all, the design professions exist to conceive new environments for the benefit of our society at large. They don’t exist in isolation.

Landscape Architecture is for everyone.

–

Michael Smith is an architect and co director of Atelier Red+Black. He is a passionate advocate and activist for built environment environment issues and is the consulting architect for the Built Environment Channel, Australia’s cutting edge digital screen network.

This review was first appeared on The Red and Black Architect blog. Read the original here.