Catherine Mosbach’s “submersive” experiments in landscape architecture

Catherine Mosbach talks about time, control and learning to let go when designing for living systems.

Control

Foreground: You have spoken about giving up some control when designing landscapes but your built work shows extremely precise and beautiful design, whether in specifying materials and defining and locating elements or managing the various stages of the work. What is the relationship between ‘control’ and ‘responsibility’ for you?

Catherine Mosbach: Control is linked to the way you engage in a dialogue with a site, a program and your sensibility. The term is not best adapted to describe the process – let’s use the word ‘design’! With any project, a diverse collective of users want different things and that requires us to resolve questions of services, comfort and technical matters. That means we use our expertise and knowledge to draw together the scope of many possibilities to create a unique place. Then it is a question of what we know and play with today, and what we leave open. We do not know this so precisely but we aim to leave open a creative dialogue between present and future.

Landscape – like an animal or vegetal body – is always changing. So to think about a present, fixed ‘place’ is quite a strange way to translate our position on the earth. To make a dialogue between what you know and what you do not know, you need to introduce some conditions or rules. Language is no more than that. We cannot speak together without an alphabet and rules, but that doesn’t mean the ‘text’ of our conversation is locked or predetermined. Design is a language and it should be in continuous dialogue – in landscape design – with life happenings. Control is one ‘tool’ of that language.

FG: You seem delighted when users – human and animals – take ownership of spaces and behave in unexpected ways in your projects, or parts of them. This is, of course, another side of relinquishing control. What judgements do you make about unplanned activities? Is this a calculated ‘balance’ or an unspoken subversion or something less definable or conscious in the design process?

CM: We – I – work for public space and for many generations, not only this one. I am not an engine or a device, I am a human with a singular understanding of a context and how a question addresses a program. With the same program, five different landscape architects may propose different translations of the context and different answers to questions, even for the same place, client, and users. I understand design as a dialogue between me and the site, client and program. And that discussion is addressed to a public inhabitant, to visitors, young and old, and from different countries and cultures. A dialogue means there are exchanges. It is an open creative and fertile system, not a monologue.

For me in landscape – like in life – a ‘piece’ or project has many functions and not only one. Of course, especially for landscape, functions must already account for changes of season and longer timelines of growth. When I encounter people from different ages and cultures I am inspired and I imagine the larger public, animals included. It is a great gift to have the capacity to see and imagine as another, like all artistic work that encounters a public. That’s the goal of a public space: bringing together many kinds of life in ways that engage our creativity and humanity. But a dialogue doesn’t mean talking over the host. The origin and point of the conversation is lost with overlapping and competing voices. The design is like an introduction, the opening of an evolving movie where many lives – animals, vegetation, humans – will play parts together after being introduced.

FG: In the face of a changing climate and its unpredictable yet inevitable impacts, will a flexible approach to the types of control we have of landscapes become more necessary or perhaps inevitable? Has ‘control’ tended to create a paradigm that has contributed to pollution and global warming?

CM: Control isn’t necessarily helping worthy contributions. We are living with knowledge that is always evolving. The knowledge held by different disciplines is continuous and exponential. Great achievements rarely happen within the span of a human life but grow on the achievements of others over many years and even generations. It is linked to the tools we use both in micro life (biology, chemistry) then in macro life (astronomy, chemistry, geology).

We all live with the state of knowledge and the tools we have in our own times. We understand that the global behaviour of all populations together won’t fit with the needs of other life on earth. So we need to introduce a more subtle dialogue between our ‘human’ system and other ‘systems’. But we can only use the tools from our timeline – with enough flexibility to embrace what we do not know – and survive by being as efficient as possible. That doesn’t mean no language, no exploration, risk or creativity. If we only had to efficiently apply what we know, we could just give the task to a device, programmed to achieve technical goals. If no human thought or effort or sensibility is necessary, it means no more civilization.

Today a dominant movement in capitals and countries is to ask all inhabitants to express their ideas to contribute to the program –- that is direct democratic decision-making. I totally disagree with this. It assumes that it is not necessary to have experience and knowledge to make decisions. It supposes everyone can equally read and work through all the parameters of a problem; that everyone can do it. That is a total fiction. It actually happens when nobody wants to take responsibility for a direction. It is a way to say that expertise is not valid and everyone has an equally legitimate opinion. The result of this is what we see on social media and in the fragility of democracy.

Liberty, Equality, Fraternity was a call to control human wildness and open a dialogue to bring together individuals and communities to make decisions affecting us all. Today we need to do that with other life as well as each other. That is the great challenge.

Time

FG: Your work is renowned for the delightful and profound ways it engages with temporality and continuing change. Can you explain how you work with the perception of time in gardens and landscapes?

CM: Time is the key point of landscape. Yes, sure, you need to understand the largest processes of our environment’s evolution to anticipate further stages. But you cannot anticipate everything. Leaving the system open is a flexible way to accept unexpected events, although if you let the work be completely open to unexpected phenomenon, without a script, you actually have no project and no writing or sensitive translation. That’s the limit of ecology: just trying to reproduce what is, by definition, always ongoing anyway.

I try to engage time. There is no choice because it is reality! I typically introduce several layers of rhythms, meaning several rhythms of growth. An urban landscape needs to be interesting for all seasons, whether with bare earth, or with overflowing rain, mixing young trees with mature trees so that there is always a transition like in real life. A project should consider each season and connect us to the real facts of the landscape, not a kind of final product to be presented as merchandise.

The main problem in our practice, is that a project can take from five to eight years. Then the commission is done. But that is only the beginning and the initial conception has to be followed by maintenance. What is fabulous in our practice – which is the opposite with architecture – is that landscape architecture can continue to work with inherited projects over time. But that supposes the translation is respected – like in Versailles for the last 400 years – and this is very rare and problematic.

Learning

FG: You have referenced Steiner’s theory of 12 senses and suggested that the bodily experiences of landscape can play an educational role in a city. In particular, you suggested that the landscape installations substituted for planned ‘climate devices’ as part of Taichung Gateway Park should be used as educational tools for schools. What types of knowledge can or should designed landscapes ‘teach’?

CM: The mayor requested we look at Steiner philosophy. We were not aware of it. And Taiwan, like many countries, experiments with alternative ways to learn. Basically it means more interaction between teacher and student, more transverse knowledges, more care about bodies that is not only about appearance, but about complex interactions with the world. What that actually meant for the park was that the architect’s climatic devices focused on only one function per installation and for a small group of users, which made them quite expensive furniture.

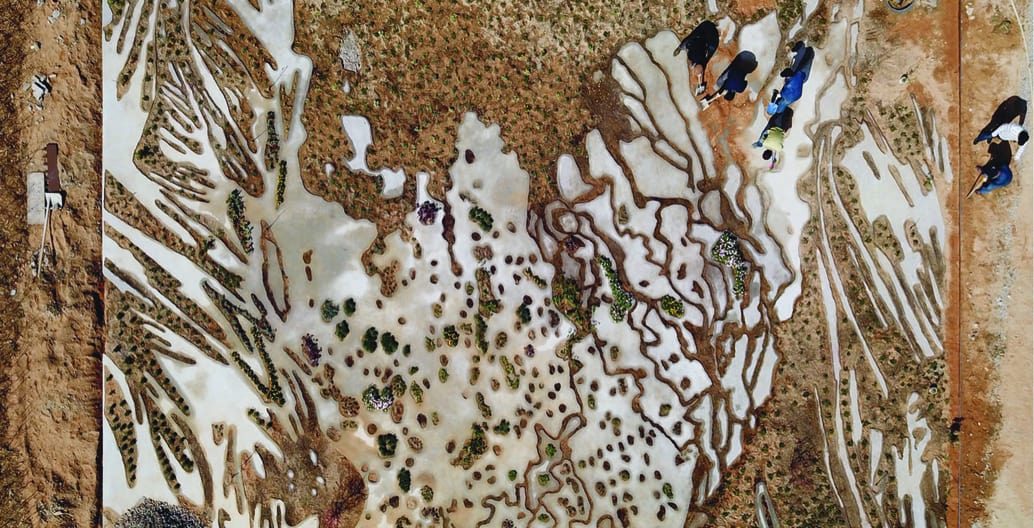

Taiwan’s Phases Shift Park is polysemic – it has many meanings and offers many ways of approaching and appreciating change rather than just through immediate climate mitigation or manipulation. That makes it very powerful and efficient for future inhabitants. Outdoor life is very unusual in Taiwan because of a lack of comfort. So testing and learning about your body with and compared to other bodies, including animals and vegetation, is a way to open your mind to other things you do not know. So the project of a park is a social and political investment, working both for individuals and for a collective capacity to evolve and create together. And this is the key lesson for sharing and surviving.

FG: You have spoken of ‘the thickness of the nourishing factor’ of design. Can you tell us more about what ‘nourishing’ means?

CM: My background in biology, physics and chemistry covers the parameters of life on earth. Since I developed Pages Paysages I have met many inspiring people who nourish my curiosity. In occidental culture we are used to seeing and evaluating only the results of investigations as fixed conclusions. But in Asian cultures what we see is never an end, just a passage through different stages. That means, to create a life process you need to understand where the result is coming from, so you are able to evaluate that result.

The request in Bordeaux for the Botanic Gardens was ambitious and I did not want to reproduce the invisible on the surface like a ‘museographer’ showing stable object ‘fossils’. Real life is much more powerful than our brains can imagine. So let’s play with real life, and teach people to evolve in real life without being afraid of what is hidden. Actually, Bordeaux is much more powerful than what I could have imagined. But then there are other weaknesses – life is never perfect.

FG: Your projects render unseen and subsurface things visible – making ‘representations in the literal sense’ as you say of Bordeaux Botanic Gardens. Can you explain how miniaturisation and shifts in scale have become a useful tactic for you?

CM: As we are not gods, and will never be able to create mountains or seas, we need to find a subterfuge to make as if we can. Scale is a very delicate subject, the main subject I have dealt with since I started practice. Is like an apartment where you can have only 30 square metres and you can make it look super large or super small. Or like your skin. From one metre away it looks very simple, just an envelope. Yet close up it is a planet of holes making exchanges between inside and outside. Our ‘dream’ is to have something beautiful in front of our everyday window. A very large area can look small because the body is dominant and sees all around in one glance. Or a small piece can seem very large because you design it to engage the brain on many levels. Like Alice in Wonderland. I have done three small pieces – Quebec 250sqm, Xian 1000sqm, Ulsan 500sqm – and all look like they are endless. And I like to dream – then invite guests to dream too in their everyday life!

FG: In their enjoyment of the Botanic Gardens, some people did not notice that it was nature recomposed, but thought it was merely part of a landscape transported to the site. Some might think it is desirable for a project to seamlessly replicate or be mistaken for nature. What is important to you about interpretation and its distinction from imitation?

CM: There is a lot of misunderstanding about botanical gardens. But like life – and like movies or books – each critic is responsible for their interpretation. Imitation is not a way to go for me. It is like a play-back. We are interested in ‘direct’ not in ‘replay’. Life is instant, a continuous work-in-progress that is a great show – so let’s appreciate it and emphasise it in our cities. Some critics said that at the Louvre-Lens I ‘Japanized’ my design, as if in the occident we cannot have another way to think aside from some mainstream, accepted and familiar manner of organising and ornamenting space. Sanaa did not ask me and I did not develop a design to follow Japanese style. As a landscape architect, I want to make possibilities seem as large as possible so as to open the mind to imaginative exploration. I dissolve the limits as much as I can.

At Bordeaux, miniaturisation is the main tool. Without it you cannot represent twelve environmental landscapes in two hectares! Yes, that means we need to use techniques to keep the scale through timelines. And although it is efficient today, we will have problems later, because one large tree in a particular spot on the earth has nothing to do with a forest representing an environment. A representation is what the name says – a translation, not one to one, nor imitation. Would a lover give an imitation gold jewel to their beloved? No. The same goes for landscape. I imitate nothing. I just try to be inspired with the power of what exists to look beyond what we know, because our life has a limited span and little time to discover its many ‘treasures’.

To make in interpretation you need to adopt the position of an outside viewer. Like a photographer, or a movie maker. That gives you the power of translation. If not, you are not able to propose a script. But then, yes, for me landscape is powerful when you are submerged, you become like a phasme, you are no more dominant just a small piece from a larger one, as in fact we are! We are nothing in astronomy’s knowledge and timeline, just an accident or a project linked to the interpretation we give to a component, brewing together with others. Victor Hugo explains that very well in his written work and drawings. And we all go back to stars, so we need to train beforehand – a submersive experiment so as not to be surprised.

–

Catherine Mosbach is the founder of Paris-based design firm mosbach paysagiste, which she established in 1987, as well as the magazine Pages Paysages, which she co-founded with Marc Claramunt, Pascale Jacotot and Vincent Tricaud. Catherine graduated from the École Nationale Supérieure de Paysage of Versailles in 1986 after studying biological sciences and physical chemistry at the University Louis Pasteur Strasbourg. She is renowned for socially and environmentally responsible work that attests to temporality and continuing change, referring those who interact with these landscapes to relationships with history, culture and the elements. She was a speaker at this year’s Living Cities Forum, presenting in Melbourne and Sydney.