Caring for Country: how remote communities are building on payment for ecosystem services

An economic model that pays remote Indigenous communities to care for Country is here: payment for ecosystem services. The model utilises locals’ valuable knowledge and skills and, as one of the only forms of employment available in remote areas, is providing vital support to communities.

The payment for ecosystem services (PES) model is supporting a new wave of self-determined construction on Aboriginal homelands.

With no secure strategy for government infrastructure investment in homelands, particularly in new housing or new homelands, PES provides an alternative approach to support meaningful livelihoods on Country. Importantly, revenue from PES can support self-determined and appropriate building there.

PES can attract funding from government, such as for ranger programs, and from private sources, in the form of carbon credits and corporate social responsibility funds. Research suggests it’s also “crucial for improving social outcomes for Indigenous communities”.

Other researchers argue that payment for ecosystem services is “most effective” on remote Aboriginal homelands and outstation settlements where it fundamentally values cultural knowledge and where the vastness of the landscape allows for economies of scale.

Indigenous PES enterprises can harness both traditional Indigenous knowledge and contemporary science for land management that improves environmental quality. Examples include activities like carbon abatement, feral animal management and biodiversity conservation and restoration.

On remote Aboriginal land, PES is often one of the few enterprise opportunities. That’s due to such restrictions as distance from economic centres, poor access, skilled labour shortages and limitations on Aboriginal land tenure, in particular the limited capital and security held. Commonwealth laws prevent the buying and selling of this land.

The example of Kabulwarnamyo outstation

Kabulwarnamyo outstation displays how PES activities simultaneously cause and provide a way of meeting the demand for buildings on remote Aboriginal land. And often this happens in ways that are more responsive to the local context than current government-provided alternatives.

Kabulwarnamyo is a small outstation of about 50 people on Warddeken Country in West Arnhem Land, Northern Territory, about an eight-hour drive from Jabiru. It is extremely remote and cut off for up to five months of the year during the wet season.

Established in 2002, Kabulwarnamyo is managed by the not-for-profit company Warddeken Land Management. This followed the Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Commission’s (ATSIC) moratorium on creating new homelands due to the Australian government no longer funding the building of houses on them.

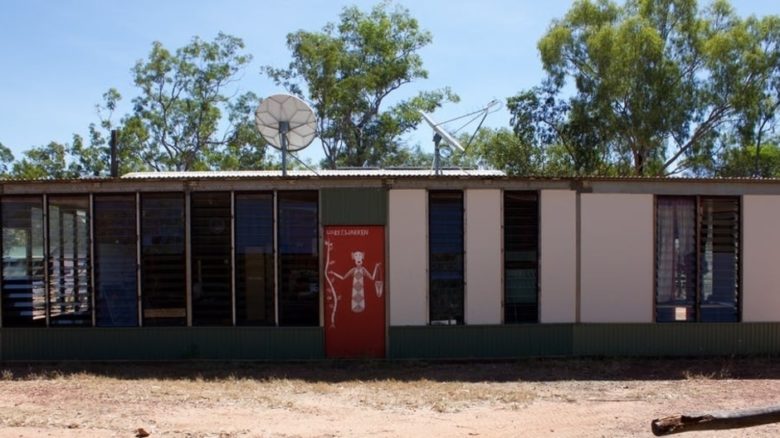

Ecosystem services paid for the self-built office at Kabulwarnamyo which includes doors painted with totems in the traditional X-ray style. Photo: Hannah Robertson

An early version of the balabbala at Kabulwarnamyo with a double-layered tarpaulin reduces heat gain. Photo: Hannah Robertson

Payment for ecosystem services supported the building of the Kabulwarnamyo school - a modified balabbala with a central truss. Photo: Hannah Robertson

PES activities – namely carbon abatement and biodiversity conservation – are the core business of Warddeken. However, it also built 14 dwellings on the outstation using an A$80,000 grant from the NT government and PES funds from the sale of carbon credits to multinational energy company ConocoPhillips.

The flexibility of the carbon credit funds meant Warddeken could build in ways that directly responded to the needs of the people, rather than adhering to centrally determined regulations, which typically drive up building costs.

To establish Kabulwarnamyo, the Warddeken rangers, who are traditional owners and residents of the outstation, self-built an office and 14 balabbala (traditional Warddeken shade shelters). A number of versions have been developed over time. Each balabbala consists of a raised timber platform floor on steel rails with local cypress pine posts and two trucking tarpaulins as a roof.

Dome or safari tents are pitched on the platforms to provide sleeping spaces and privacy for occupants. The structures have solar-powered electricity and hotplates for cooking using bottled gas. A creek-fed pump provides water. A separate structure houses a shower and long-drop toilet.

Excluding wages for construction staff, each balabbala costs A$15,000. These simple structures do not adhere to public housing standards, but do meet crucial local needs. The balabbala project has allowed Warddeken rangers to conduct PES activities and maintain cultural connections to Wardekken Country in the absence of government funding for services support.

Evolving to meet local community needs

As Warddeken’s business has developed, so too have the building typologies. In 2015, Warddeken self-built a school to enable children to also return to living on Country. The school is a modified and extended balabbala, built using Warddeken Land Management core funds.

A crowdfunding campaign raised ongoing teaching funds. Financing the running costs of the school remains a challenge. Unlike remote non-Indigenous townships, there is little NT government support for homeland education.

The school, like the balabbalas, represents this community’s reinvestment of PES-derived funds to meet their crucial needs in innovative ways. The Nawarddeken Academy was formally registered as an independent school in December 2018. It is clear these unconventional buildings are fit for purpose and satisfy the registration requirements of the NT Department of Education.

PES-enabled balabbala are not the ideal solution for building development on homelands. But here they are appropriate because they are simple and largely suited to the environment and the cost of building them matches available funds. Warddeken CEO Shaun Ansell has said:

What we do at Kabulwarnamyo is appropriate for our resourcing, environment and capacity, but it’s not proper housing. If we had the capacity to build beautiful mud brick houses for everyone we would.

There are long-term plans to improve the balabbala using locally sourced stone for half-walling. This will retain the structures’ passive ventilation properties while improving protection during the wet season and cold weather. The structures can therefore be seen as staged projects, improved as resources become available.

Most importantly, the balabbala provide significant social returns to local Nawarddeken. A 2014 report by Social Ventures Australia, commissioned by the Department of Prime Minister and Cabinet, documented significant social, environmental, economic and cultural benefits as a result of PES investments at Kabulwarnamyo. It estimated the value of these outcomes at A$55.4 million for the financial years 2009-15 – a return on investment of $3.40 for every dollar invested.

Lessons from the Warddeken experience

The Warddeken experience shows us the policy conditions that could support building and PES enterprises on other remote Aboriginal lands. These are:

- implementing government policies that recognise, or at least do not inhibit, self-driven building initiatives

- loosening restrictions on using PES carbon credits and Working on Country funds to support building that directly responds to needs arising from living on Country

- providing incentives for urban-based corporates to support remote PES partners and a widespread environmental strategy

- recognising the value PES creates beyond an environmental return

- continuing government support for PES economies in remote Australia.

As Warddeken has shown, buildings play a critical role in enabling PES. The flip side of this is that PES supports building in response to locally identified needs.

Payment for ecosystem services provides extensive environmental benefits, but it is the broader social and cultural returns, such as maintaining connections to Country and creating sustainable livelihoods, that are most meaningful on remote Aboriginal land.

–

Dr Hannah Robertson is Innovation Fellow and Lecturer, Faculty of Art, Design & Architecture, Monash University. She has worked on building and design projects with Indigenous communities in Cape York and Arnhem Land, Australia.

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

![]()