The Piano Mill: In remote rural Australia, a living culture builds on the musical bones of the past

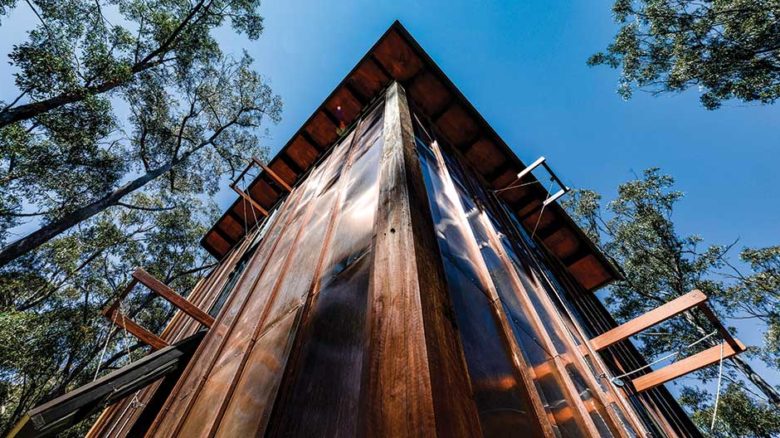

A musical instrument at the scale of a building, made from the carcasses of 16 outback pianos, the Piano Mill has beaten a slew of big name, big budget projects to take home a World Architecture Festival Award. What is it about this folly in a forest that has drawn such global admiration?

It has been variously described as a unique architectural structure, art installation and performance machine, a mechanism, one instrument made up of 16 and a new home of place-inspired music and art. As a mill it is somewhere between a rustic grain mill (minus water wheel or sails) and an oversized designer pepper mill. Closer to a grain mill in scale and in its working integration with landscape, it is also like a lovely domestic pepper mill in the particularity and crafting of materials, its empty core and its contribution to the shared-table spice of life.

Adding to its swag of Australian music and architecture awards, The Piano Mill has just received global recognition, winning the Completed Buildings – Culture category at the World Architecture Festival (WAF) 2018 in Amsterdam. Competing against much larger structures, what is it about this remotely-located folly that embodies lessons for the world?

The structure is a timber-framed, copper-clad box, nine metres high with 4.5m sides suitable for aligning two upright pianos. Two interior levels, together housing 16 reclaimed pianos, sit above the ground around a hollow access atrium. Large louvres can open and close to modulate the music made within, while additions such as copper megaphones help to amplify it.

Set in eucalypt forest on a remote private property in south-east Queensland near Stanthorpe, The Piano Mill was the creation of architect Bruce Wolfe of Conrad Gargett, composer Erik Griswold and artistic director Vanessa Tomlinson. However, from the first performance, the greater Piano Mill project that has grown around this structure (joined now by another special venue) has engaged a long list of people in making and curating, contributing to and enjoying this unique, landscape-embedded space. These have included the pianists, other musicians, movement artists, video artists, recording engineers, chefs and friends with food, neighbours with fireworks, and more.

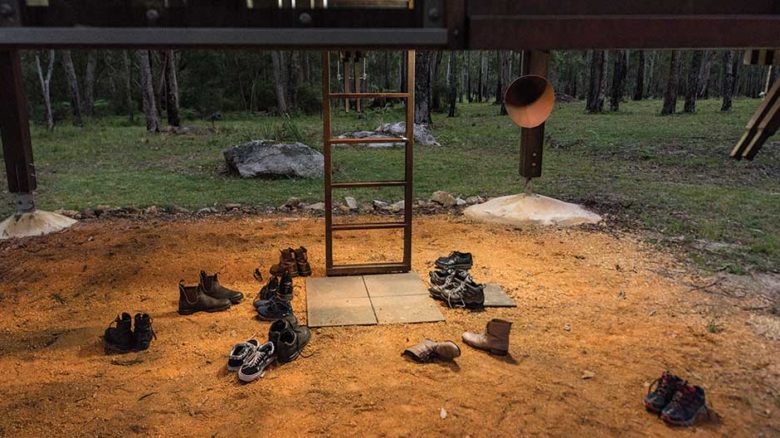

The audience too is arguably part of the piece, even if they had not helped with other aspects of the performance delivery. They can certainly choose how to hear the composition, whether seated somewhere particular or moving around the structure and listening from different points to receive different impressions.

Preparing for a performance at the Piano Mill.

One of the Piano Mill's 16 repurposed pianos at play.

Acoustic road-testing of the Piano Mill.

The architecture of pianos

Pianos are a tool of an earlier age, an instrument that colonised the world with the colonisers (a piano arrived with the First Fleet to Botany Bay in Sydney, the property of navy surgeon George Bouchier Worgan). They have been adopted by new cultures and adapted to new climates, temperaments and practices. From the concert halls and salons and then public houses of Europe, to frontier saloons, outback missions and jungle prison camps, pianos were a reminder of home and link to civilisation, if not also an incentive to civilise.

Still, a piano is not something to tuck under the arm and skip town – or your country – with. In the recently published A Coveted Possession: The Rise and Fall of the Piano in Australia, Michael Atherton tells the particularly rich tale of Australia’s keyboard-instrument relationships. It is a story of politics and passions, protectionism and invention, cutting across all social classes and geographic regions.

While researching for his architectural thesis in 1975, Wolfe learnt that Australia had more pianos per capita than any other country at the turn of the 19th century. Pianos increasingly became an anachronism with the introduction of radio, television and livestreamed family entertainment. Old, unloved uprights have found some seasonal life during festivals and in city streets, as happens regularly now in Adelaide.

When Wolfe met composer Erik Griswold, who works with prepared pianos, he recalled Australia’s historical affair with the instrument and the idea for the Piano Mill took hold.

Making music, making place

The outcome of collaboration, The Piano Mill and its ongoing project of events and gatherings provide encouragement for wide-ranging interdisciplinary work, attracting diverse engaged audiences. Award-winning London-based collective Assemble describes a collaborative practice that seem likely to get wider traction. Peter Raisback is hoping so in his blog and others too are questioning the dynamics of responsibility in renumerated design relationships. This reflects an idea of shared resources and risk that can be seen in endeavours such as those of New Orleans’ Airlift. Leaving aside pianos and recognising this is an urban environment, their Musical Architecture project conceived in 2010 nevertheless has many similarities to The Piano Mill.

Re-housing of an outback piano in the Piano Mill.

The Piano Mill's louvres open and close to modulate sound.

The Piano Mill is nurturing a culture.

Unique sonic experiences can be found in naturally occurring and built spaces. Documented places with unusual acoustic qualities include Whispering Galleries and other structures with accidental fun sound features, as well as enhanced or modified environments such as ancient amphitheatres and post-industrial arenas, improvised auditoria, unintentional echo chambers and architectural auditory follies. The 2017 Adelaide Festival hosted a sellout season in the Hills in Anstey Quarry, now a bookable event space. In the age of noise-cancelling headphones, we remain intrigued by the unexpected ways sound can affect us when experienced with the other visual and tactile apprehensions of a place.

The experience of music-making and sharing is a transformative one. It has also been a much more common one in the past, both in the family home and through social institutions such as church and school. The ABC documentary Don’t Stop the Music has just aired to popular acclaim, evidencing the positive effects of teaching and learning music in primary school.

Similar to many other creative activities, and driven by new technologies, passive consumption is replacing active creation. Yet the complicated, multi-directional cultural journey of the piano belies an argument of simple binaries: the good old days versus modern times (whenever either of those are said to be), acoustic versus digital, high versus low art. Perhaps consumption once required more active engagement, with technology now out-sourcing judgement for us as smart systems pre-determine optimised choice. We need the experiments of The Piano Mill project’s music and architecture to be surprised by discovered desires and to make more fun.

Architecture, music, environment – and people

In writing about the launch of the project, Tomlinson and music academic Jocelyn Wolfe have spoken eloquently of the collaborative and contextual significance of music-making. As spatial designers well know, we “engage with a place in a multitude of ways, through all the senses. Musically, we are all an extension of a place where meanings and feelings are ecologically derived and socially and ritually embedded”. They speak of site-specific art, describing three modes of flux that the Piano Mill plays with: the sonic flux of manipulating the building structure, the visual flux of the changing scenery and light, and the environmental flux of unpredictable flora and fauna and weather, birdsong and rain, insect buzz and mist. But the other vital component in flux is the people.

The experience of any art is unique to its time, place, and atmosphere but also the people you share it with, present or not. The influence of all these factors is something that landscape architects often acknowledge, whether by openly embracing them, or seeking to control or frame them. The achievement of The Piano Mill is its inclusive appeal to people interested in the instrument and the music made for and from it, but importantly also in the remaking of the wider site variously as practice, performance and listening venue with each event. It hints at new models for collaborative cultural production and for its broad acceptance and enjoyment.

We are taught respect for certain enduring values and their tangible past captured in buildings, documents, practices and even people. However, valuing the ongoing exemplary records of the present remains a less popular, if no less rewarding, effort of exposure and learning. The heritage of the future is now and it is venues such as The Piano Mill that are building awareness of great work while making it. It is nurturing a culture. The Piano Mill heralds more than a tinkering around the edges of accessibility for experimental music or contemporary architecture. It is a finished instrument for the ongoing development and sharing of enduring creative work, a fitting recipient of an award for ‘Completed Building – Culture’.

–

Dr Jo Russell-Clarke is a senior lecturer in the School of Architecture and Built Environment, Adelaide University, and a registered landscape architect and Fellow of the AILA.

The Piano Mill is the subject of an eponymous book published earlier this year by Uro Publications. For more information on the book, or to purchase a copy, click here.