Paradise lost: The forgotten landscape legacy of Marion Mahony Griffin

An exhibition of Marion Mahony Griffin’s design highlights how our obsession with the singular object and heroic author has worked to obscure the transformative impacts of ecological and cultural skills and knowledge.

Legacies are unstable, even at the best of times. The reputation of Marion Mahony Griffin, Chicago-born architect, artist and partner to Walter Burley Griffin, suffered a more dramatic reversal of fortunes than most. The first woman in Chicago (and the United States) to be registered as an architect, a key member of Frank Lloyd Wright’s studio for more than a decade, and a pivotal force in producing the Griffins’ plans for Canberra, Mahony died a pauper’s death in 1961 at the age of 90. Her death certificate mistakenly lists her occupation as “Teacher in a Public School.” Her marital status incorrectly transcribed, too, as “never married.”

Paradise on Earth is a new exhibition at the Museum of Sydney dedicated solely to Marion Mahony Griffin. While modest in scale and execution, it points to the significant progress made in recent years to properly acknowledge Mahony’s considerable design talents and achievements, and her efforts in pioneering a role for women in the architecture profession. Over the past three decades, this reconstruction of Mahony’s legacy has intersected with important feminist interventions concerned with unveiling the gender biases of the architecture industry.

THR Wilson House, Castlecrag c1929. c National Library of Australia

Walter Burleigh Griffin and Marion Mahony Griffin, Castlecrag. Photographer Jorma Pohjanpalo, c1930. National Library of Australia (detail).

View of Castlecrag houses under construction c1922 (c) National Library of Australia

As Elizabeth Birmingham proclaims in her ground breaking 2006 essay on the reception of Mahony’s life and work, all too often, “if it is feminine, it is not architecture.” In other words, the recovery of women once lost to history, like Mahony, is never as simple as merely telling otherwise untold stories. It relies on a more profound cultural shift in what we value, pay attention to and emphasise. On the Mahony legacy, Anna Rubbo is equally perceptive in her assessment that in “an age characterised by competition, and the desire to create stars or ‘heroes,’ the collaboration between Marion and Walter Burley Griffin […] provides another paradigm through which creative activity can be viewed. Marion Mahony Griffin emerges as larger than life but not as an architectural hero.”

There has been much productive reappraisal of Marion Mahony Griffin through the filter of gender. Paradise on Earth provides an opportunity to consider her legacy through another lens; namely her connection to nature and, in particular, the significance of her unique mode of landscape-led design. The twin impetus of the exhibition is the 150-year anniversary of Mahony’s birth and, simultaneously, the 100-year centenary of the establishment of Castlecrag, the bushland suburb in Sydney’s Middle Harbour. Mahony and Griffin envisaged Castlecrag as a model for residential planning founded on a sympathetic response to natural topography and the fusing of the built environment with its landscape setting. Twist the kaleidoscope towards the rapidly maturing field of landscape urbanism and yet another Marion Mahony Griffin emerges—a woman clearly ahead of her time due to her progressive ideas on architecture and community building, caring for land and the inherent sustainability in placing ecological systems at the centre of urban design.

While the terminology might not have existed at the time, the planning and design of Castlecrag was from the outset what we would today recognise as a textbook exercise in landscape urbanism. It’s a chapter in the Griffin story that begins just prior to 1920 when, after one too many years of bitter struggle with the bureaucracy over their plans for Canberra, Walter Griffin finally severed ties with the project. Seeking a fresh start, the Griffins turned their attention to Sydney where they scoped several sites until settling on the purchase of a large tract of undeveloped land on the north shore. Spanning three headland promontories, the site caught their eye as “the only large area of unspoiled landscape left on Port Jackson” (despite being heavily denuded of vegetation at that time).

It was here that Mahony and Griffin set to work on developing the idiosyncratic residential estate that was to become known as Castlecrag—a sort of “Garden Suburb” gone wild in the rugged antipodes. Griffin walked the rocky terrain to map a network of contoured roads and carved the site into an organic plan of varied lots considerably smaller than was fashionable in the period, opting to follow the natural boundaries of the peninsula rather than impose a rectilinear grid. A suite of building covenants was also drawn up (inevitably leading to many disputes with future purchasers), stipulating a preference for a materiality of stone and concrete for houses, unfenced and topped by low-lying flat roofs, all set within a meandering array of shared internal reserves and open spaces. In an article for Australian Home Builder, published in 1922, Griffin described Castlecrag as an “idealistic development,” conserving for residents “all the remarkable natural features of the place—its outlooks, monumental cliffs, caverns, ancient trees, fern glens, wild flower glades, waterfalls and foreshores.”

Castlecrag residents 1930-33. Image: National Library of Australia

View of Castlecrag houses + surveyor with Theodolite. Walter Burleigh Griffin circa 1920-23. (c) National Library of Australia.

Creswick House at Castlecrag with Anice and Frank Duncan during construction circa 1930. (c) National Library of Australia

Griffin may have published the manifesto but Mahony echoes these sentiments in her own words in her unpublished autobiography, The Magic of America, which attests to the fact that the pair realised Castlecrag in close partnership. Reflecting on the legacy of Castlecrag from the perspective of its 100-year centenary, the question of what is worth remembering and valuing in the present rises to the surface again. Were the Museum of Sydney’s exhibition to have been presented 20, or even 10 years ago, it is easy to imagine that the focus would have been squarely on the suburb’s architecture. While the residences of Castlecrag are unique and worth celebrating, Paradise on Earth is curated with an emphasis on the community of Castlecrag. This reflects a social turn in the current urban planning paradigm, of which, in the context of the Griffins’ body of work, Marion Mahony Griffin in fact emerges as the main proponent.

Mahony was raised in the tightly knit enclave of Hubbard Woods, Winnetka, a pastoral Illinois neighbourhood known as an intellectual haven, and the progressive values instilled during her upbringing were brought forward into adulthood. Her architecture studies at MIT were supplemented with art classes, in which she excelled, and she maintained a lifelong interest in drama and theatre. At Castlecrag, the idealistic principles underpinning the estate’s design, many of which harked back to Mahony’s formative Chicago years, attracted environmentalists, bushwalkers and others drawn to an active community life. From 1926 onwards, the suburb also became a hub of activity for spiritualists following the Griffins’ contact with members of the Theosophical Society in Sydney. The binding glue of the Castlecrag community, however, was the open-air theatre productions organised in large part by Mahony and staged in the stone tiered outdoor theatre designed by Mahony and Griffin in 1934. It was at this “First Scenic Theatre,” Mahony writes in The Magic of America, that “plays on the natural rocks amidst the trees and flowers of the Cranny Cove have been given each of the four seasons of the past years,” all this made possible “in such an atmosphere of conscious plan.”

The final Christmas Carols held in 2019 at the Haven Amphitheatre, before it was demolished in 2020. Image: Matthew Keighery, courtesy of Castlecrag.org

An early play staged at the Haven Amphitheatre, Castlecrag.

An enactment of 'Marion's Gift', a play staged at the Haven Amphitheatre in Castlecrag, which included life-sized puppets of both Marion and Walter. Image: courtesy of Castlecrag.org

Mahony’s recollections point to the value she afforded the amphitheatre and its close connection to her concept of the neighbourhood, her deep affinity with nature, and the importance of the quotidian, with its acts of sharing and exchange as providing the foundations of civic society. In recognition of the fact that these intangible and ephemeral moments of architectural history are the most difficult to capture in the static format of an exhibition, a key innovation of the Museum of Sydney’s exhibition is the inclusion of Enchanted Valley, a large-scale immersive reimagining of the Castlecrag amphitheater filling a whole viewing room. Aimed at children with its invitation to climb, play and explore the space, the scene of kids bursting with delight at the rolling projections of Castlecrag scrub enlivened by a soundscape of bird song and the flashing pulse of an LED illuminated rivulet makes it possible to grasp in an intuitive, rather than pedagogical fashion, the visionary intent at the heart of the Griffins’ planning and design ethos.

Yet in turning over the main exhibition space to a single installation, it is a pity that the modest selection of Mahony’s plans and drawings, for which she once earned high praise from Reyner Banham as “the greatest architectural delineator of her generation,” are afforded less than ideal viewing conditions along corridor spaces. Mahony’s circa-1914 perspective view of the JG Melson Dwelling at Mason City, Iowa, for instance (part of a larger integrated landscape plan for 19 houses, five of which were built, and a blueprint of sorts for the ideas pursued a decade later at Castlecrag), is considered a master work of 20th century architectural drafting and it alone warrants placement within a dedicated viewing room.

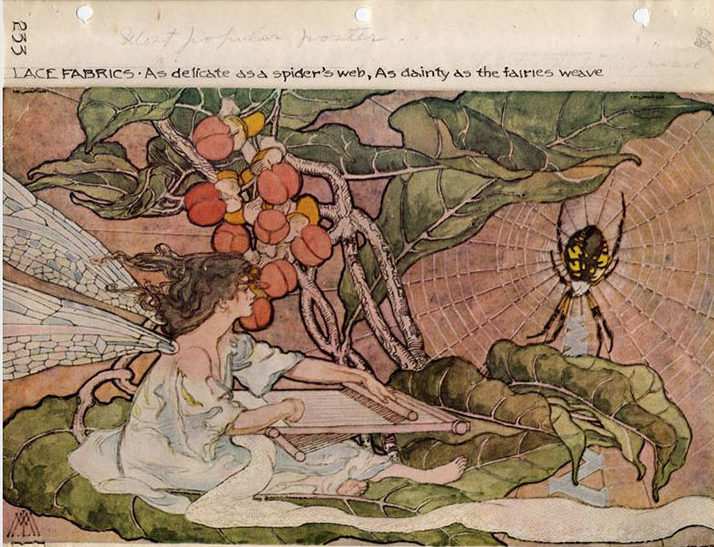

Influenced by the close interrelationship between nature and buildings found in Japanese art and the elegant linework of ukiyo-e prints, Mahony’s drawings are profoundly biophilic. During the Prairie School years, where she worked alongside Frank Lloyd Wright who drew his foliage precisely with rulers and triangles, Mahony adopted a more naturalistic style, and her drawings are alive with the vitality of the freehand sketch. In Mahony’s plans, flowering vines and plants cascade down terraces and viewpoints are cleverly selected to render buildings subordinate to the natural environment. More than just aesthetically beautiful, the drawings reveal a love of nature founded on a belief in the restorative qualities of landscape and its spiritual potential too, as the Griffins saw it, in functioning as an antidote to the rapidly modernizing world that they found so alienating.

Importantly, Mahony’s drawings are also repositories of botanical information and point to her contribution to the Griffins’ advocacy of indigenous plantings and the placemaking potential they afforded to local flora stretching back to their designs for Canberra. Following on from the Newman College garden Mahony embarked on a massive botanical inventory, compiling a comprehensive list of native plants for use in planting schemes tabulated to show different growth requirements and foliage features. The high point in her botanical rendering is the impressive suite of large-scale tree studies, known as the Forest Portraits, produced in part during a month-long sketching trip to Tasmania undertaken in 1918 and which record “the diversity of forest types, the unique beauty and form of these ensembles, at a time most Australian gardens were rose-and-dahlia and gladioli-mad, and relatively few were championing native plants,” as Stuart Read has pointed out.

It’s now been some 22 years since scholar Anna Rubbo wrote in her 1998 essay for The Griffins in Australia and India that “architectural history traditionally tends to approach its subject through one of two interpretive routes: architecture-as-object or architect-as-author. Marion Griffin’s role, or the way she represents herself, doesn’t fit neatly into either form of discourse.” Paradise on Earth acknowledges this fact and gestures towards the alternative legacies that might emerge when nature, community and social life are made the focal point of histories of the built environment, rather than architectural objects and singular design heroes. This particular showcase’s relative paucity of primary materials means that a comprehensive survey of Marion Mahony Griffin’s work still remains to be staged in Sydney, but when it arrives the ground will have surely shifted such that an appreciative audience will at last be ready and eager to receive it.

Paradise on Earth, curated by Dr Anne Watson and presented by Sydney Living Museums, is showing at the Museum of Sydney until 18 April 2021. Find out more here.

Ella Mudie is a writer and researcher based in Sydney, Australia. With a background in English literature and arts journalism, her work is focused on the geopolitics of the built environment and the representation of space more broadly in literature, photography, and the visual arts.