Beautiful ugly. Ugly beautiful: Painting the Australian landscape

Award-winning artist Idris Murphy has been painting the Australian outback for decades. In the third of a series of Landscape Conversations, Murphy speaks about what keeps him seeing anew.

Idris Murphy is a prominent Australian contemporary landscape painter, who has exhibited extensively since the late ’70s. His work is held in a number of Australian collections, including the National Gallery of Australia, the Art Gallery of NSW, and the State Library of Queensland. In 2014 he won the Gallipoli Art Prize. In this most recent Landscape Conversation, a podcast exploring how a diverse range of creative people engage with the idea of landscape, Murphy reflects on half a century of painting the land. The following is an edited excerpt.

Anton James: What informs your idea of the landscape, as opposed to something existing outside of your window?

Idris Murphy: Well, let’s start back to front. Certain indigenous language groups don’t have any word to refer to how we conceive of landscape – like how we ‘view’ the landscape from urban contexts, which is rooted in European consciousness. One source of the word landscape comes from the Middle Dutch landscap, referring to a painting’s representation of natural scenery. Even with a word such as wilderness, it has nothing to do with the Australian landscape, as it was derived from Old English’s word for wild deer.

I remember reading about the early colonial experiences of the ‘bush’, where they talked about being ‘drowned’ in the landscape. Some settlers went into the bush and never came back.

AJ: Did you have a close relationship to the bush as a child?

IM: I initially grew up in Bankstown, which is sort of peri-urban. Then we moved to Sutherland Shire, which was the bush. My dad was a forest officer, so I had his farming background. Anything to do with the bush, Dad was in.

AJ: So landscape for him was something akin to an inventory?

IM: I hadn’t thought of it in those terms, but you’re probably right. He imbued my brother and I with a love of native stuff. My aunt had a property in Wyong and I used to go and stay there and go fishing by myself and wander around the creek with the smell of wet leaves and seeing birds and ducks and all sorts of animals floating around the place.

I grew up in an Australia that sat on the coast. In the eighteenth century the British built their houses facing the sea because they couldn’t bear to look at such an uncontrollable, uncontrolled world. When Captain Cook arrived, that started the process of kicking the indigenous people out, via invasion if you will. My interest in landscape lies in places that haven’t been touched by this process.

Sand dunes in the Sutherland Shire, Sydney.

The Simpson Desert's wild flowers after the rains. Image: John Benwell.

(Eucalyptus coolabah) in the Simpson Desert. Image: John Benwell.

AJ: How do you choose your subjects? What do you look for?

IM: The outback pulls on all of the senses. The colour and remoteness of the outback forces you to drop the things you once relied on to conceptualise the landscape. Those things that are recognizable are inherently paradoxical. Take dams. Built by early settlers, most of them rarely hold water.

You don’t have church steeples or the meandering river or the little bunch of trees. You can’t really fall on these clichés because they aren’t really there. What is there, however, is vast distance, exquisite sunrises, sunsets and silence.

AJ: For me, whether it’s painting or landscape architecture, both present an idea of the landscape. What is it that we’re communicating? Is it the aesthetic? Is it the experiential?

IM: It’s probably all of those at some level. Anything great, like music, architecture, or painting, seems to have something to offer at nearly all of those levels. In a western tradition, it is reasonable to think back in time, and think about how something was constructed and why it was constructed. In other words, we can try to understand a language.

AJ: Do you think understanding a language has challenged the way you look at the Australian landscape?

IM: Without a doubt. When I was at Winchester College of Art, and more generally when I was in Europe, I was basically painting bad Matisse paintings. But I couldn’t give a bugger about any kind of ‘Australian landscape’. People were still teaching how to paint a Cézanne, when most had never seen one. When I came back to Australia, the first thing I saw was a Fred Williams series of small landscapes and I understood why he was what he was – a bloody good painter. I realised then that the only thing I really cared about was the landscape.

In fact, before I went to art school, I was enrolled to go to an agricultural college because that’s the only thing I was really interested in. But really, in many ways, the question now is how do we define landscape in the twenty-first century?

John Berger asks, after cubism, is there any great landscape to be possibly made? This question is what keeps me coming back to the Australian landscape. Here, the Western painting canon can’t really apply, so for me, it gives me a way to bend the concepts and traditions I’ve been taught from a western context. The critic John McNoll wrote about my work: “Beautiful ugly. Ugly beautiful.” Which for me was really perfect in a sense, because it finally brought about an understanding of what I’m trying to do in my work.

AJ: Ugliness and landscape are things that don’t come up that often?

IM: Well no. But one of the great writers in history, art and psychology, EH Gombrich, wrote a book on the ‘primitive’ in art, which I guess relates somehow to this ugly-beautiful binary. One thing that’s stuck from that book is that we can’t ‘choose to be primitive’.

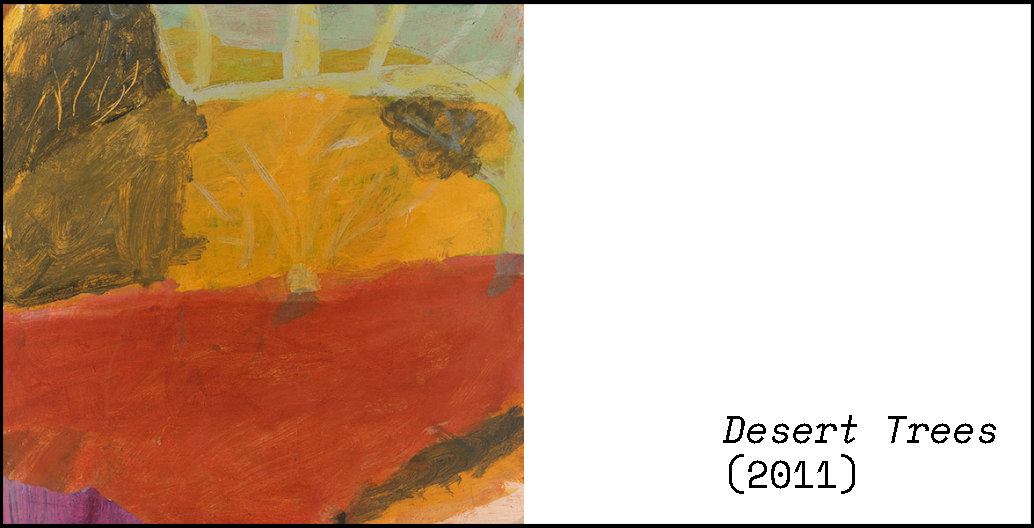

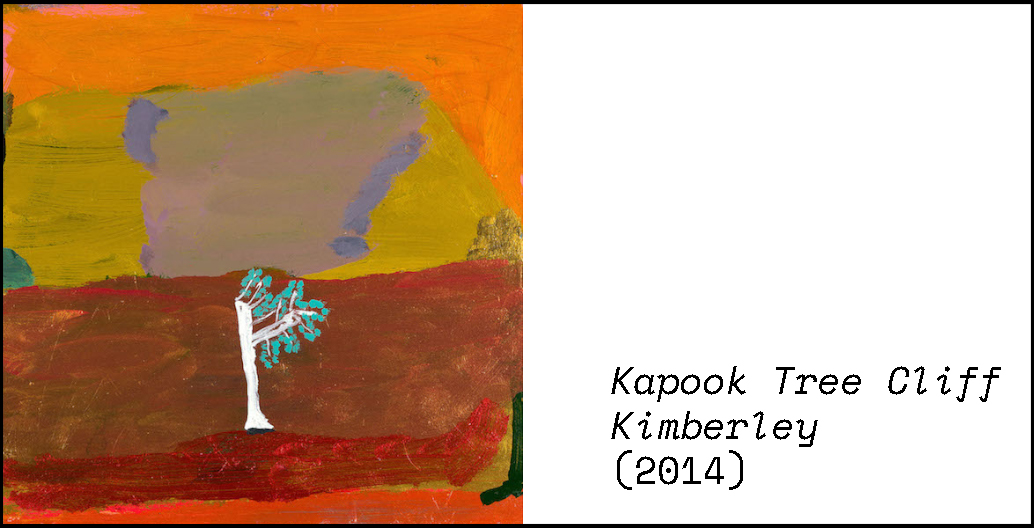

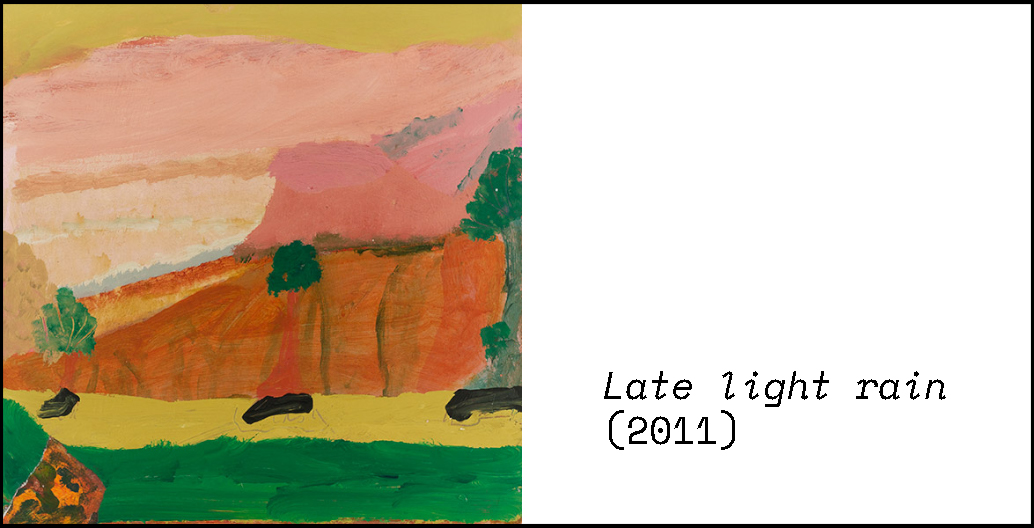

Artwork courtesy of the artist.

Artwork courtesy of the artist.

Artwork courtesy of the artist.

Artwork courtesy of the artist.

AJ: I noticed a map just before, and that prompted me to think about the aerial view. To what extent does the horizon inform your work?

IM: Professional landscape painting is based on a horizon that in many cases defines its form: background, foreground, middle ground or whatever the tradition is. For me, I think about how indigenous people describe the land and their surroundings. The central desert’s lived experience for example, is all about looking down. Because, if you’re starving to death and you’ve got to find a lizard that’s under a rock, you’ve got to actually find the track that leads to that rock.

AJ: That mirrors mapping because you’re working downwards on a flat surface.

IM: Pollock worked like that. I have the canvas there on the easel, and I paint something on it for a while. Then I throw it on the ground and can have five or six of these boards on the floor. But I still see through a western lens: to see from top, bottom, right and left – I don’t want to deny that. What I’m interested in is marrying Western and non-Western ways of seeing. That’s what I’m really interested in.

In the outback there are a lot of rivers that are dry, but flow once every five years. Occasionally there’s a big flood and timber will build up around a beautiful ancient redwood tree, which is every kind of shape. There are holes in it. The bark has beautiful lines in it. It’s a magnificent thing.

AJ: Do you think what you leave out and what you include becomes really telling?

IM: Any creative person would acknowledge that on one level or another, something happens in work that you realise you didn’t do. The creative process is, in some ways, giving up control and allowing things to present themselves. Then sometimes you acquiesce, or perhaps better… you say yes to it.

––

The Landscape Conversations podcast explores the diverse ways in which landscape is worked in, thought of and defined. Its guests in conversation include landscape architects, scientists, artists, filmmakers and others who shape how we understand landscape. Subscribe here.