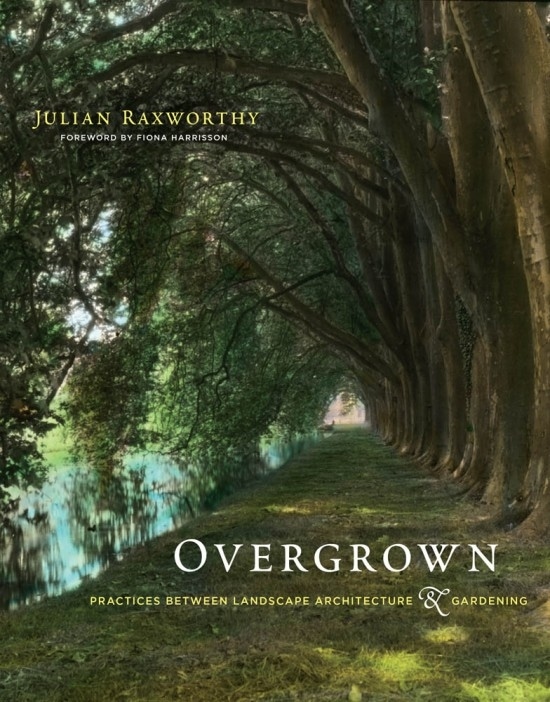

Overgrown: a call for landscape architecture to return to the garden

Most would consider gardens and gardening as central to landscape architecture, but this rich relationship has been repressed. Julian Raxworthy calls for landscape architects to get out of the office and back into the garden.

[This is an extract from Overgrown: practices between landscape architecture and gardening by Julian Raxworthy, © 2018 by Julian Raxworthy. Reprinted by arrangement with the MIT Press, Cambridge, MA. Click here to purchase a copy from the Uro Publications bookshop. ]

Garden or Landscape?

Issues of maintenance are important to all landscape architects. Since this book is directed at them, landscape architects might ask: “Why talk about gardens?,” when public landscapes are also in desperate need of care. I will conclude this introduction by setting out why I believe that the garden is the ideal place to consider growth, and the relationship between landscape architecture and gardening.

The garden is the root of landscape architecture, yet a fraught site for the profession. It is the birthplace of the discipline, yet one that it seeks to suppress due to its association with the trade of gardening, or amateur gardening. Nonetheless, by the time modern ideas like outdoor living were becoming of interest to suburban homeowners in postwar America, the residential garden again became a site for landscape architectural practice, once the link to gardening and gardeners had been broken, and the profession was well established. The garden as the root of the profession is periodically invoked by designers who talk about “getting back to basics,” and is synonymous with a call to renew interest in plant material.

The garden has always been a place where modernist landscape architects “test” ideas—Swiss landscape architect Dieter Kienast, for example, who famously explored topiary and wetlands in his home garden in Zurich. Both Rose and Eckbo used the garden as a testing site for ideas. In his graduation design project from Harvard, “Small Gardens in the City,” Eckbo designed a series of 18 hypothetical residential gardens. Using the same site issues and design palette in different ways, he developed a project that was “purely abstract and experimental, designed to stimulate thought and provoke comment, discussion and flow of new ideas.” Sven-Ingvar Andersson, Roberto Burle Marx, and Geoffrey Dutton all tested ideas and ways of using plants in the gardens featured in this book.

Another reason why the garden is trivialized by landscape architects—more so than by architects—is that it lacks many of the constraints faced by public landscapes. While I hope that my discussion of the political dimension of gardening as a trade demonstrates that I am not interested in autonomy, it is true that I am focusing on the garden because it is less easily hijacked by other issues than public landscapes are. The garden allows a specific focus on plants. In so doing, though, I acknowledge that having a garden is a privilege acquired through economic advantage and is not available to everyone, a fact that does potentially undermine some of my claims about gardening as a trade.

The garden is always practical and philosophical, and these two are and always have been linked. Dixon Hunt, reading Cicero, suggests that gardens are ‘third nature’: first nature is wilderness, second nature is mobilized for human gain, like agriculture, and third nature is the garden, essentially functionless, where nature—that is, plants—are mobilized for aesthetic purposes. While the garden as third nature has different intentions to second nature, it shares with it the manipulation of plants, albeit for different ends. In the garden, this manipulation is gardening. Therefore, I argue that the garden and gardening are synonymous, and that this activity is foregrounded in the garden. Correspondingly, since gardening is one of the foci of the book, the garden is the logical place to discuss it.

Mark Francis, in The Meaning of Gardens, discussing the “everyday garden” of the amateur home gardener, argues that gardens are “a place to exert creativity, … to experiment with creative fantasy [and] to experience the joy of creating something.” Acknowledging the amateur roots of gardening by focusing on the garden, I hope that this book will also appeal to regular gardeners who might be interested in the relationship between gardens, as they understand them, and the profession of landscape architecture. Much of the gardening techniques and biology that I discuss will be familiar to gardeners; therefore the spatial and formal discourse of landscape architecture might allow them to see what they do in their garden from a perspective more informed by design.

Landscape has come to mean either public landscape or urban landscape, despite its English landscape garden roots. Landscape is now linked to infrastructure, to programs like schools or building types like business parks. The garden, on the other hand, is self-referential, and about plants. This alone is a reason for landscape architects to be less interested in it. Indeed, efforts by the early profession to distance itself from plants show the trivial regard for plants by landscape architects generally. Due to its association with plants, the garden is also regarded as trivial, compared to public landscapes and infrastructure. My primary reason for choosing the garden is that gardens are acknowledged to foreground growth, which is the central focus of this book.

That does not mean the book has no relevance for landscape maintenance—very much to the contrary. Maintenance means to “keep (something) at the same level or rate.” A narrow focus on landscape maintenance would cause the creative potential of growth to be obscured by the instrumentality of maintenance. Ideas about growth in the garden can stand separate from the banal pragmatism of landscape maintenance. It is from this perspective of creative growth that, I believe, a conjunction of landscape architecture and gardening offers a whole new realm of design practice.

–

Julian Raxworthy is a Landscape Architect from Australia with 25 years practice and academic experience. Initially working as a landscape tradesman, he studied at Ryde Horticulture TAFE, later becoming a landscape architect after graduating from RMIT, Australia. He has a PhD from the University of Queensland, where he is a Honorary Associate Professor with the ATCH (Architecture, Theory, Criticism and History) Research Centre. He is currently residing in Dubai, after 5 years in Cape Town.

This is an extract from Julian Raxworthy’s book Overgrown: practices between landscape architecture and gardening (MIT Press 2018). Click here to purchase a copy from the Uro Publications bookshop.