Fostering native plant literacy with Field Guide

The internet is getting a new publication dedicated to Australian native plants – and it comes with a nursery, too.

Australia is no stranger to cognitive dissonance when it comes to identity. It is the driest continent on earth, yet its people are the second-highest consumers of water per capita in the world. In popular culture, its vast interior is romanticised, yet Australians live, work and play along the coastal rim. Such contradictions also resonate in our urban landscapes and gardens. While popular gardening magazines and prime time gardening shows attract large audiences, few could name more than one or two species of native plants.

That’s where Field Guide comes in. Launching in early 2018, Field Guide is a new publication that hopes to foster greater literacy in native plants and Australian gardening culture. Partnered with Austem – an organisation that advocates for Australian flora – the publication seeks to be a first-port of call for beginners to find out the how, what, and why of growing native flora.

Foreground talked to inaugural editor Connor Tomas O’Brien about the inspiration for the publication and how its readers can better engage with local flora.

Foreground: We understand that Field Guide was initially going to be a digital encyclopaedia of native flora. What led to the shift to a digital publication?

Connor Tomas O’Brien: A lot of information about Australian flora is hard to find, and locked away in fairly old multi-volume encyclopedias. The goal initially was to figure out how to bring it up online. But an encyclopedia takes a pretty all-or-nothing approach. It also means that you usually have to know what you’re looking for, to use it.

We wanted to respond to the novice: so the person moving into a new property, who’s trying to figure out what to do with their garden. Where do they go, to begin to find out about native plants? So think of Field Guide as a starting point, with different stories pointing people in obvious directions. From there they can either identify what flora to buy from our nursery, or take the knowledge from our articles to buy from native nurseries around Australia.

FG: How does the nursery factor into the publication?

CTO: We are going to be supporting the content through selling boxes of native plants, grown out of a private nursery in Victoria’s Mornington Peninsula. The first box is all about iconic Australian flowers. For example, one of the features that I’d like to commission is about the Brown Boronia that some people say is the best-smelling flower in the world. So, it’s not exactly just about visual aesthetics. It is also about the added dimension of smell.

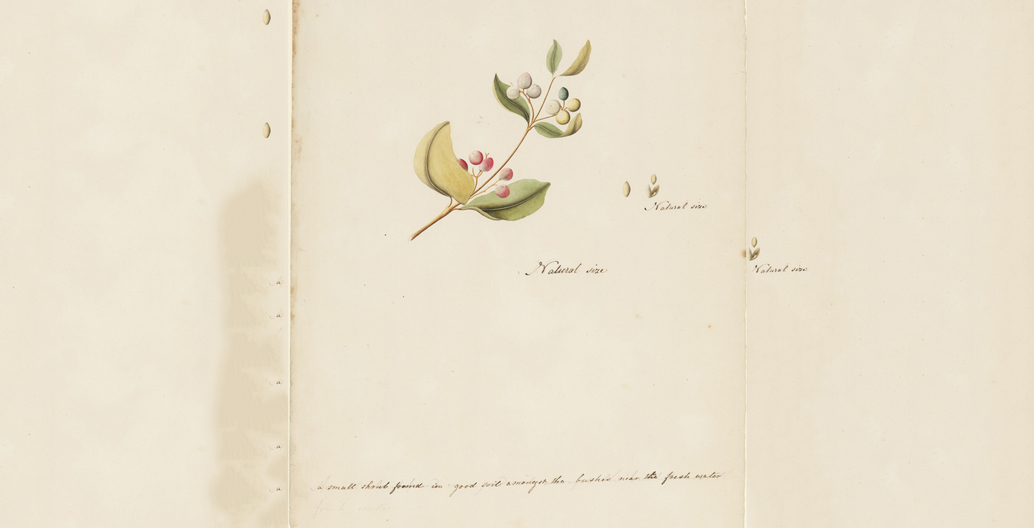

Original drawings by Captain James Wallis and Joseph Lycett, ca. 1817-1818. Image: Mitchell Library, State Library NSW.

Early European representations of Australian native plants. Image: State Library of NSW.

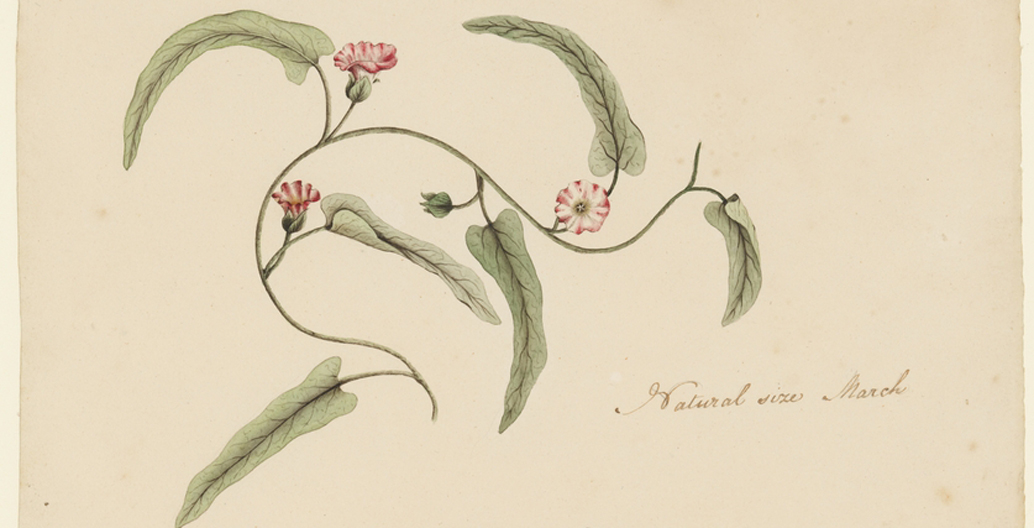

Botanical drawings of Australian plants, ca. late-18th century. Image: Dixson Galleries, State Library of New South Wales

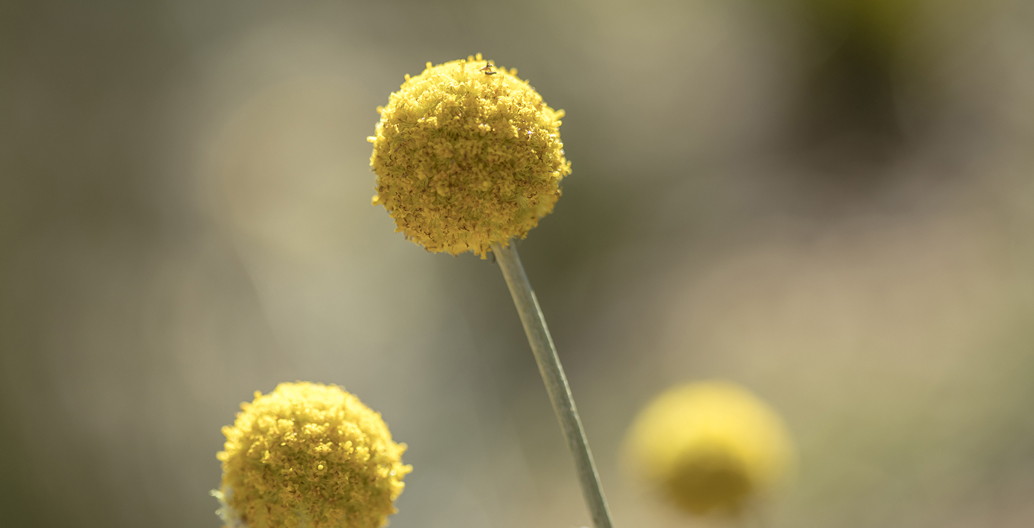

Australia's Billy Button flowers are a Pinterest favourite. Image: Field Guide

FG: Why do you think Australia’s knowledge of its native flora is so mixed?

CTO: I think maybe in Australia, more than anywhere else, a disconnect between the ‘natural world’ and cities exists. Lots of people travel to a national park and engage with native flora there. But then when they get home, there is a disconnect between native flora in a national park, and that on the nature strip.

FG: That level of engagement in indigenous planting does seem to vary from state to state though. Certain states have a strong native planting tradition, while others have a stronger colonial tradition. During the development of Field Guide, were you aware of these distinctions across Australia?

CTO: Yes, I think that it’s different from region to region. Around Perth it is very, very strong compared to other cities. Queensland’s basically living in a wonderland.

Generally, there’s a high degree of engagement, but it does take different forms. It does seem to relate to how people engage with national parks, how they see nature, and where they think nature begins. Do they consider where they’re living as a natural place? Of course, there are plants that are seen as native to Australia, but considering how large the continent is, they might just be indigenous to Western Australia. They are then transported vast distances to sit in gardens on the eastern seaboard.

‘Moon Lagoon’ planted in the bump layer of a woody meadow garden. Image: John Rayner

The Astartea Fascicularis is one of the plants comprising the base layer of a Woody meadow. Image: John Rayner.

Staff and students plant Melbourne's Woody Meadow at Birrarung Marr. Image: Claire Bolge

FG: Can you name any significant Australian gardens or parks that specifically engage with native planting?

CTO: There are two gardens that come to mind, one being Alan Schwartz’s Redrock, and the other by landscape architect Paul Thompson. There is also a university-led project called Woody Meadow that looks at the relationship between aesthetics, conservation, and plant literacy. It’s a collaboration between the Universities of Melbourne and Sheffield, exploring the aesthetics of native plants in public spaces, and how people react to them. So it’s interesting to look at this from a university research perspective. In time it will be good to have the data that comes from this research, because then other bodies can utilise this body of knowledge.

FG: To what extent have you sought direct input from the Indigenous community?

CTO: At the moment we’re still in the pitching stage, so I can’t talk specifically to what’s being incorporated. But certainly we consider Indigenous voices and Indigenous writers to be really key. One of the things we want to do is address the idea of botany being a colonial exercise. Obviously it’s not the primary thing we are going to be doing, but I think that’s a necessary corrective in this context. Botany is inherently political. That said, commissioning Indigenous writers and engaging in Indigenous culture doesn’t have to be always political. We’d like to celebrate the ways in which Indigenous peoples have used native flora.

FG: Earlier in the year you opened for submissions. Are there stories that you can talk about at the moment?

CTO: Opening up the pitching process was interesting because it confirmed some of the suspicions about what I thought people might be interested in. A lot of people are interested in incorporating natives into gin-distilling, and cooking with natives, which is a thing that makes a lot of sense considering the increasing literacy with native plants, and obviously food culture has exploded over the past decade. I have also had pitches that spoke to creating dyes with native plants. So essentially, people are interested in looking at more than just gardening. People are interested in stories that speak to native plants engaging with other components of culture.

—

Field Guide will be launching in early 2018. Follow developments here, and the publication is currently open for pitches.

Connor Tomas O’Brien is a Melbourne-based writer and designer. He is the inaugural editor of Field Guide.