“Listen first, and look closely”: Thomas Woltz on storytelling and landscape architecture

Thomas Woltz wants to bin the binary opposition between “city” and “nature”. For him, they’re one and the same. The US-based landscape architect talks with Foreground about the importance of revealing landscape’s hidden cultural histories and championing its democratic potential.

Thomas Woltz’s Nelson Byrd Woltz Landscape Architects describes its projects as a “body of work that integrates the beauty and function of built form and craftsmanship”. What’s missing there is the practice’s role in curating history. Over 19 years, it has been tasked with expansive projects dealing with literal and figurative historical layers for clients and countries alike.

Right now, Nelson Byrd Woltz Landscape Architects are tasked with creating a living garden over Manhattan’s rail yards, and over in Australasia, they repaired a Kiwi coastal headland that witnessed the migration of the Maori and British to the long white cloud.

Initially trained as an architect, Woltz says his turn toward landscape architecture was inspired by its potential to develop “resplendent, high-functioning ecoystems”, as opposed to a building’s “long journey back to dust”. While under the stewardship of the University of Virginia’s then-architecture dean William McDonough, Woltz was introduced to design that carefully understood its sense of place, “its climate, site, regional materials and culture”, with the work of Glenn Murcutt on high rotation.

While there are plans afoot to open an Australian office – and a current Tasmanian project in the works – Woltz had a chat to Foreground expanding on his perspectives on landscape architecture’s role in championing genuinely democratic public spaces and his “eco-humanist” approach to design.

Foreground: The distinction between ‘landscape architecture’ and architecture has been a fairly recent one. You could argue it’s more pronounced because of professionalisation. Do you find this distinction useful?

Thomas Woltz: Yes, because I wish we were trained to know how to use the tools of the other profession better. I wish both architects and landscape architects were taught the need for a very healthy and respectful collaboration across discipline boundaries. But I think there is plenty to keep people busy for three or four years of graduate studies to become professional. There would be a lot of material to try to convey in one master’s program.

FG: Previously, you’ve talked about humanism as being the beginning point of design for you, while also talking about your practice’s ecologically regenerative approach. Is there a tension between a human-centred approach to design and this idea of “ecological restoration”?

TW: No. The humanism with which we practice is a humanism seeing our species as part of nature, and therefore part of an ecosystem. This binary construct of “city versus nature” has harmed us. When you start to think of a city as a living organism that has a metabolism – the raindrop that falls being connected to the street, to the parks, to the sewer lines, the drainage ways to the river, to the sea – you start to see it as connected, just like the arteries of the human body.

We need to start thinking about the city in a different way, and it’s a much healthier mode of urbanism when we realise that everything’s connected. That’s why I think landscape architects are well suited to solving urban problems because they inherently think at a large-scale. They know that the natural world doesn’t care for ownership boundaries, and so we literally have to think outside the square daily. I feel that when someone who makes objects is asked to make a city, it sometimes can become a city of objects as opposed to a living city.

Orongo Station, New Zealand. Image courtesy of NBW.

Orongo Station remains a working agricultural landscape. Image courtesy of NBW.

NBW planted 500,000 trees to reforest the site as part of the Orongo Station masterplan. Image courtesy of NBW.

Over 75 hectatres of fresh and saltwater wetlands were restored or reconstructed at Orongo Station. Image courtesy of NBW.

FG: You have worked on two huge projects in New Zealand – Orongo Station and Cornwall Park more recently. Relative to North America, New Zealand could be considered remote – particularly Orongo Station as an ex-sheep station – so I’m curious as to how the commissions came about.

TW: The client was actually someone I went to university with, whom I had already worked for in the US. He’s a passionate environmentalist, and when he and his wife purchased the land, they asked us if we wanted to be involved and propose ideas for such a rich landscape. Then we began to repair what farming does to a landscape of that nature, like draining wetlands, coastal headland erosion, and the clearing of temperate rainforests, among other things.

We did three other projects for American clients, one in the South Island, one in the North Island and then the Cornwall Park commission came about thanks to our prior New Zealand works.

FG: How did these projects fare alongside agricultural practices?

TW: My time in New Zealand taught me about large-scale reforestation. Cornwall Park gave me a precedent I now use in the states, that being the use of livestock to manage large-scale open spaces and public parks. Currently in the US you use noisy and polluting gang mowers, which aren’t great for wildlife and very disruptive when experiencing a park.

Typically in public parks it’s forbidden to do agriculture and so having livestock onsite technically tells authorities that we’re engaging in agricultural practices. We’re starting to get around that. Nashville’s park service has just hired us to look at two 500-acre parks and an 800-acre park that we’ve started on. By doing this, we hope to remind people of what “productive” landscapes are… I feel a lot of kids have absolutely no idea where their food comes from.

FG: Do you feel the Orongo Station project has an impact beyond the site itself?

TW: I mean, it’s important to remember that the site is where the British sighted what became New Zealand, but it’s also the landing site of early Maori migration so it’s witnessed two very important moments in New Zealand’s history. So in doing this project, we’ve had to bring a balance to both the land and its history. We are not in any way celebrating those specific dates or those specific moments, but these events shaped both the Pakeha and Maori history of the site.

But I don’t know how to answer that really. My hope is that it is setting a positive example that people can look to and emulate. It’s really helpful for me to see a project realised when in the process, I wasn’t sure of how to do it in the first place – it’s a great example for me to refer back to… but if you find anybody who considers it of help, please tell me because that would make me very happy.

One Tree Hill, Cornwall Park, Auckland.

Thomas Woltz, image courtesy of the Australian Landscape Institute of Architects.

One Tree Hill, Cornwall Park, Auckland.

FG: At your RMIT guest lecture, you mentioned research is always the starting point in any of your design projects. Why is this so important?

TW: Research gives you a considerate framework in which to approach a piece of land, it articulates the land’s story and informs how your contribution will sit in relation to what’s come before. A quick rule of thumb for any practitioner: before you invent the heroic gesture, you listen first, and you look closely.

FG: Is it fair to say then, landscape design is a kind of storytelling?

TW: Yeah absolutely, and I think in the landscape, so often important stories of the past have been muted or destroyed either through time or successive transformations. The landscape either evolves naturally or is forced to evolve to make it unrecognisable from what came before. But there is also another kind of transformation, and that is the erasure by who gets to tell history.

In the United States, there was a period after the Civil War where wealthy industrialists from the north would buy up land in the south because of the climate, the views and the beautiful, admittedly extraordinary, architecture of southern plantation homes. But in the process, they would erase every trace of the enslaved landscape: foreman’s buildings, slave cabins, slave quarters, smoke houses. All of these structures that were part of the enslaved people’s landscape were removed because they were not attractive. Of course, the industrialists from the north didn’t need to farm the land. Instead, there were horse farms and things like it. So that’s one group of people erasing and defining history in a particular way. By looking carefully at these different histories you at least become aware of the stories embedded in a site. As soon as you’re aware of these layers, you can amplify and show those stories that have become invisible.

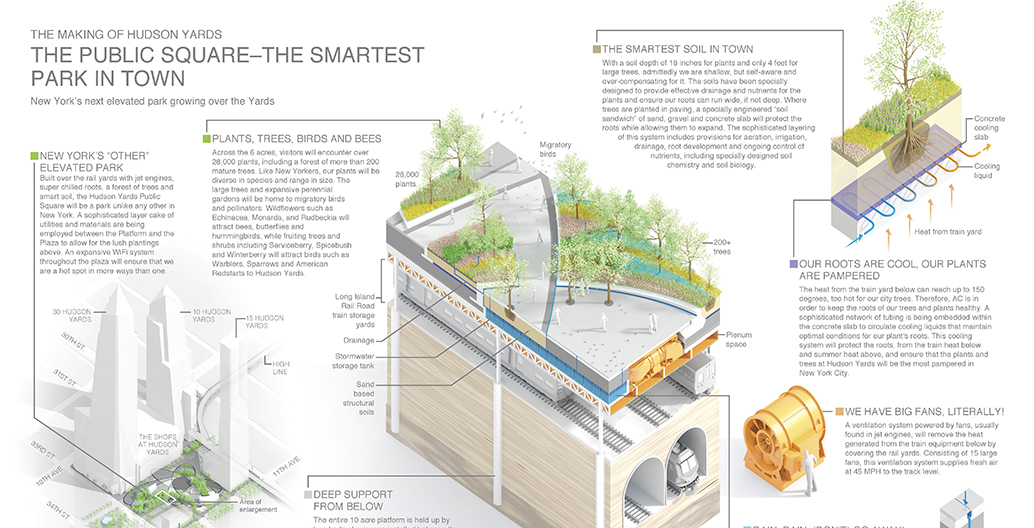

FG: In the lecture you presented a fantastic cross-section of a garden and trees on top of an active train yard. Obviously, a huge amount of hidden design and engineering allowed that to happen, while all the public will see is the planting. Would there be a value in making those hidden systems visible in some way?

TW: The artefact below [a railyard built in 1985 for train storage] is not really as compelling as our imaginations would lead us to believe. The way that we satisfied our curiosity with the site was to look back at what this edge had been, because the edge of Manhattan historically was between the Eastern and the Western yards… And that’s when we discovered, thanks to Jill Jones who was a historian that we consulted on the site, that this had been the site for drilling a tunnel that connected Manhattan and New Jersey for the first time in history.

Previously, people had to take boats across the mile-wide Hudson River because it was impractical to build a bridge in that era, the technological capability wasn’t there. The fact that our very creative marvel of engineering of today is allowing the site even to exist over the rail loft builds, which just so happen to sit on the tunnel’s drill site. And that’s when we had this idea of the double helix tower, allowing us to reveal layers of history without actually taking you on a tour of the underworld.

FG: So is it fair to say there’s a fairly sophisticated subsurface engineering that needs to exist to keep the vegetation of the site alive?

TW: Yes, it’s a pretty innovative system in and of itself. It’s a concrete slab but it is filled with coils of glycol. The glycol is cool and it super chills the slab so that the soil will be the natural temperature of the earth. The trees can then survive the heat generated by the trains below. So we are in a very thin situation where we have the bottom of the slab right above the roofs of the trains, and then an average seven-foot layer and then the surface. Without cooling, the heat generated below would overheat the soil.

The Hudson Yards originally pictured. Image courtesy of NBW.

Cross-section of the Hudson Yards project. Image courtesy of NBW.

An artist's rendering of the Hudson Yards plaza. Image courtesy of NBW.

FG: I suppose I’m curious about at what cost is it to keep these living systems alive, and the considered process city planners need to have in place to nurture the scope for these environments.

TW: A more positive way to have this discourse is that many American cities have grown without careful thought of the public realm. Many American cities have not left ideal space for roads, bicycles, parkways, greenways, street trees or sidewalks even. So you end up with a park desert in many major American cities, where good planning was set aside for developer profitability.

So what we’re seeing now is a little bit like Sydney’s Barangaroo, where cities haven’t thought ahead properly and have to innovate to create public space over existing infrastructure. We are doing a project in Atlanta, Georgia where there’s a nine-acre park proposed over an eight-lane freeway that runs through the middle of the city, and it is where a park needs to be, but we have to go to great expense to build public infrastructure on top of public infrastructure.

But it’s also quite inspiring that landscape architects are the ones leading the charge to return parks and public space back to the city.

FG: The Hudson Yards project has copped a little bit of criticism for driving gentrification in the area. Is there any realistic prospect of a landscape architectural project actively working to ensure diversity amongst its user base?

TW: One of the reasons we have turned so much of our portfolio to public parks is that these are our last democratic spaces, where money isn’t exchanged for access. It is incumbent upon us to push back against the over-programming of public parks. There are so many programs and things happening that you’re expected to pay for, in turn creating hierarchy within a park, that we have to be very vigilant about. The focus should be on making safe, open spaces and interventions that are culturally resonant with a locality. Landscape architecture definitely an important role to play in standing up for those values.