Learning from the landscape: Linda Corkery

In the early 1980s, Linda Corkery was one of a number of North American landscape architects that migrated to Australia, transforming professional training and practice. Foreground speaks with the influential practitioner about her journey from the plains of Iowa to the University of New South Wales

Foreground: Your early life was not spent in Australia. For landscape architects the landscape itself often seems influential. Can you tell us a little about where you grew up?

Linda Corkery: I was born in Iowa, so I’m a Midwestern girl and up to the age of twelve, my family lived in a small rural town. My backyard, beyond a lilac hedge, was basically a cornfield. The strong geometry of agricultural patterns has probably stuck with me quite a bit.

My family moved to Phoenix, Arizona when I was twelve and I had my high school years there. It was a big change. Besides the disruption of moving from a town of 6,000 to a city of about half a million, I hated the desert. It was so different to the Midwest: I missed the seasons. There was no snow, no trees that dropped leaves. People had gravel in their front yard, with cactus. It all felt very foreign to me. Looking back, I realise I learned to love and better understand the desert landscape after I’d lived in Australia for a few years.

Foreground: Were there people or events that influenced your early career?

Linda Corkery: I went back to Iowa for university, but didn’t actually start out studying landscape architecture. Those were the years of the Vietnam War and lots of social unrest—serious distractions. I switched majors regularly. For most of my early undergraduate years I was an art major, but I eventually graduated in a new major that combined coursework on housing and urban planning.

I enjoyed my undergraduate years mostly because of all the extra-curricular activities I got involved with. One of those was the University Lectures Committee. I was a student member with this group that planned the annual speakers program for the university. And one of the academics on the committee was Jim Sinatra, then a popular young lecturer in the landscape architecture program who, of course, later moved to Melbourne to rejuvenate the landscape course at RMIT.

I think it was in my second year, Jim hosted Ian McHarg for a public lecture. McHarg spoke to an audience of 2,500 people! It was just one of those amazing moments–being electrified by the presentation and enjoying the bonus of socializing with him at the reception afterwards. It was a totally inspiring experience. Looking back on it, what a hoot that Jim Sinatra and I would meet again here, on another continent!

Another memorable uni experience took place during the annual spring arts festival – a week of extraordinary events going on around campus: music, performances, and so on. One was presented by Anna Halprin, who conducted one of her “happenings.” The participants all met in a gym, and danced and constructed an environment and, you know, became a “community” for a few hours. It was all very exciting. And so through that, I became aware of Lawrence Halprin.

Foreground: Had you known of him before?

Linda Corkery: No, I don’t think so. But, that following summer, on a family holiday to San Francisco, we visited Ghirardelli Square, which had recently been redeveloped, and I loved it! I learned later that Halprin had designed it, and I was excited about the idea that people actually designed cities, and places like that. And so, my eyes were being opened to those sorts of things – all very, very exciting, presenting lots of possible directions.

Foreground: A key thread in your work is an interest in environments for youth and children. This has been a consistent concern of landscape architecture but perhaps not always seen as very important or prestigious work. Is it something we need to rethink and revalue, particularly in the light of youth health problems, psychological and physical?

When I was applying for graduate schools, I had to include an essay about what I was interested in studying relative to urban planning. In my essay, I wrote about my concern for kids in cities. I was thinking about that recently, wondering where did that idea come from? And I think it was from reading Jane Jacobs. In my undergrad urban sociology and planning subjects, I had read Death and Life of Great American Cities and Jacobs wrote about the “ballet” of the sidewalks, kids playing in the streets, how important it was for them to have access to public spaces. It’s not necessarily about playgrounds, but being part of the urban scene. And that must have stuck with me.

I headed off to Cornell to do a masters of regional planning. The planning historian, John Reps, was my academic advisor. Again, I was a restless student, always looking for other things to get involved with besides the required subjects. Before too long I was recruited onto a project with another planning professor, Stuart Stein. Stu had a grant from the National Endowment for the Arts’ Architects in Schools program. This funded three masters students to work with schools to develop classes using the built environment. For example, how could you learn about history, maths, or science using the built environment? I worked with a middle school in Painted Post, New York. It was a great program and built environment education became the subject of my masters thesis.

The Architects in Schools project led me to Robin Moore’s research and design practice for creating better cities and school environments and later, Alice Waters’s Edible Schoolyard Project.

Another out-of-program thing I did was take a landscape architecture studio. This diversion introduced me two more who would influence my path to landscape architecture: Peter Trowbridge and Lenny Mirin. The studio project was a design competition sponsored by the City of New York called A Playground for All Children. The brief was to design what we’d now call an all-abilities playground. It hadn’t really been done before at this scale in a public park. The site was at Flushing Meadows, the location of the 1933 World’s Fair.

One of the advantages about being at Cornell was that Ithaca was only about four hours’ drive away to New York City. My first visits to New York were amazing, including the studio visit to the site in Queens. I worked non-stop over the Thanksgiving long weekend to get my project finished to submit. And, lo and behold, I won the student section of the design competition! The professional category winner was architect Richard Dattner, who was designing amazing playgrounds in Central Park and around the city. So I just I thought, wow, landscape architecture is great, I want to do this too!

These experiences are definitely where my interest in and commitment to designing with and for children and young people started. It has been a recurring theme in my work over the years. And it’s true: playgrounds are generally small projects and, until recently, they haven’t had big budgets. Sometimes I think there may be too much money spent on big, destination playgrounds at the expense of paying attention to all the local spaces that kids need to have in their daily lives. Children and young people in cities need to be able to safely walk to school, use public transport, to be engaged with civic life, and have access to public spaces where they’re welcome.

Foreground: What was the curriculum like in America at that time? Was there an attention to landscape systems? Was there interest in ecological sensitivity or environmental sustainability?

Linda Corkery: When I started in Planning at Cornell, the program was a masters of regional, not urban, planning. I opted for the land use, physical planning stream of study. The alternative was to focus on regional economic analysis and high-level policy planning. The curriculum structure included planning history courses, taught by John Reps. And with McHarg’s approach taking hold, we learned his ‘layer cake’ approach to landscape analysis and went through boxes of coloured markers and huge sheets of tracing paper; hand drawing all the layers. We were looking at the issues holistically, and also more regionally. So it was a more regional approach to landscape planning. Also, in the lead up to the US Bicentennial celebrations, there was a lot of interest in heritage planning, pedestrian malls, and remaking Main Street projects in cities and towns across the country.

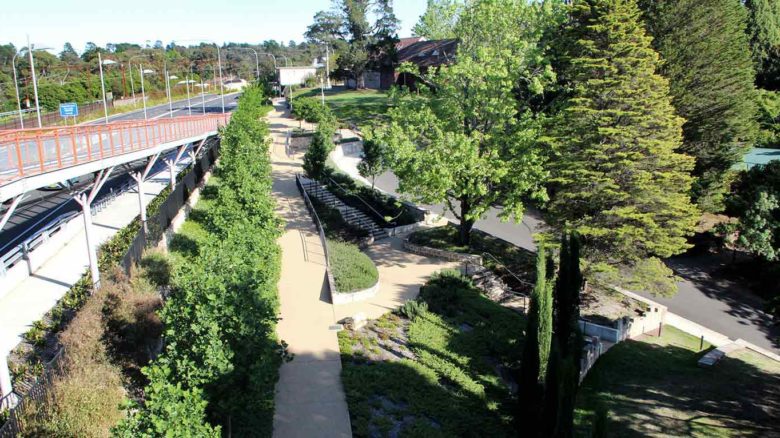

The design of Memory Park in the Blue Mountains west of Sydney deals with significant level changes to connect residential areas public parkland and a train station. Photo: Corkery Consulting

The rich planting of Memory Park reflects the cultural landscapes associated with many villages in the Blue Mountains. Photo: Corkery Consulting

Redevelopment of Memory Park formed a major component of the Highway upgrade through the Blue Mountains west of Sydney. Photo: Corkery Consulting

The first Earth Day had happened a few years earlier and the Environmental Protection Act had been passed by the US Congress. So, yes, there was a lot of interest in environmental issues and ecology. Cornell engineers were leading in the emerging field of remote sensing using the LANDSAT satellite imagery. One of my electives was aerial photo interpretation which required extra hours in the lab staring at stereo photo pairs, learning to identify landforms and vegetation patterns.

The landscape architecture curriculum looked a lot like a current program of study, with a bit more of an emphasis on plant knowledge, landscape construction and detailing. We learned landscape history and took field trips around the upstate region. One of our major design studios focused on Bryant Park in New York City, when it was still a rather dangerous area to hang out. During this time, community engagement activities and community consultation in urban redevelopment were increasing. William Whyte was busy in New York, observing, in a very systematic way, the way people use cities. I loved his work. He wasn’t a planner or a landscape architect and but his work greatly influenced urban design thinking, policies and guidelines—and we still show his film!

Foreground: With your partner, Noel Corkery, you have a practice Corkery Consulting. Can you give us some insight to the working and life partnership you have built together?

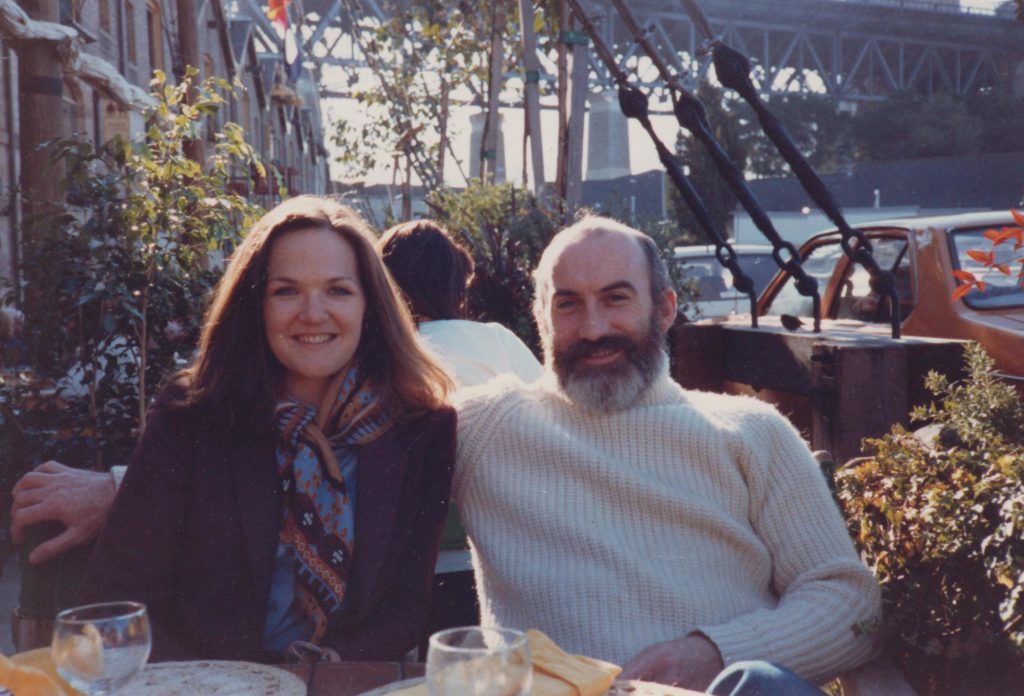

Linda Corkery: Noel came to Cornell when I was in my second year. He had done forestry as his first qualification and had been working in the Pilliga Scrub in northwestern NSW. But decided he didn’t want to be a forester. A new landscape program had started at RMIT so he moved to Melbourne to enrol in it, but later decided to go for a higher degree program in the US. In Melbourne, he’d met Rodney Wulff who was completing a PhD at Cornell and through that connection, found his way to Ithaca and was accepted into the MLA program there. There weren’t a lot of international students in our program, so this Aussie was of great interest to us all. Noel and I were aware of each other, and after I’d won the design competition he thought he’d like to get to know me better.

While he was studying, Noel was also working with Yuncken Freeman Architects in Hong Kong. Robin Edmond led the landscape group within the practice. Together with Catherin Bull, Noel and Robin set up Edmond, Bull and Corkery (EBC) with offices in Sydney and Hong Kong. When Noel and I finished our studies we didn’t get married right away. I could see that he was going to have a very intense period of time with work in Hong Kong, and I’d just put myself through graduate school, so I thought I really owed it to myself to pursue my career. I went to Chicago and worked there for three years, first in a planning consulting firm, and then I joined Joe Karr and Associates, landscape architects. Karr had worked with Dan Kiley in Vermont for many years. Kiley had come to Cornell to speak when I was there and I loved his work. Joe taught me a disciplined landscape design approach to site-specific landscape design of residential, commercial and institutional projects.

Meanwhile, Noel was in Hong Kong with EBC and we kept in touch via the occasional phone call or snail mail. Then, I had a letter from him that said he’d like to see me again. “I’ll come to Chicago and visit, or I’ll send you a ticket to come to Hong Kong.” And I replied, “I’ll take the ticket to Hong Kong!” That was my first trip out of the US, flying from Chicago to Hong Kong. It was a time when landscape architects in Hong Kong were doing landscape master planning for a series of new towns, planning, working alongside engineers on huge projects. One of the very challenging projects Noel worked on was Ocean Park where he had to site a series of escalators up the side of a mountain. It was really quite an amazing time. I subsequently returned and worked in Hong Kong for six months with EBC before coming to Sydney.

Foregournd: How did you come to move to Sydney?

Linda Corkery: Noel and I settled in Sydney after we were married. EBC transferred Noel to Sydney to help run the office there and soon after we started a family. When Allison, our first daughter, was six months old, I had a call from Richard Clough, Head of the UNSW School of Landscape Architecture. He asked if I’d be interested in teaching a course he had been running. Initially I thought, I’ve done all this study, I’m going to be a professional! The course was called, Landscape Architecture for Town Planners. With my multidisciplinary background, I thought it was probably a good thing to do, so I agreed. I have no idea what I taught! But having gotten my foot in the door, I continued teaching for a couple of years.

I continued teaching and then we were expecting our second daughter, Elizabeth, when Noel was again studying, this time doing an MBA. It looked like Noel was going back to rejoin the practice in Hong Kong, so I didn’t return to UNSW after my maternity leave. But then we didn’t go back to Hong Kong! So I thought, well, I’ll look after with the girls while they’re little and work part-time with EBC. However, when Noel had finished the MBA, Tract Consultants asked him to join them and assist with starting a Sydney office, where I then also worked.

Together, we moved from Tract to the newly formed Sydney office of EDAW. Jacinta McCann was managing the practice that had emerged out of Forsite, which was led by John Van Pelt, Ken Maher and Ian Oelrichs. I was involved with different sorts of projects to Noel at EDAW, so we didn’t work together much there. We were each developing a career, in parallel. Since 1989, we have been co-directors of a privately held company, a practice that’s been in the background during times when we were between employment with other firms but which eventually became Corkery Consulting P/L.

In the late nineties, Helen Armstrong invited me to teach her course, Environmental Sociology, while she was on leave. I accepted the invitation. Not long after the UNSW landscape program entered a period of transition. Elizabeth Mossop, who’d been directing the program, was leaving to teach at Harvard and I was recruited by Dean Tong Wu to lead the program in 1999, working with James Weirick and looking at new directions for the program. I had never thought about being an academic, but it was good move and I’ve been here ever since!

Foreground: As an educator, what would you urge students of landscape architecture to appreciate and strive for today? Would you add anything to that in regard to particular problems we face now? If you’re going to be open to opportunities, are there new ones to consider?

Linda Corkery: To all our current and prospective students, I always say there’s never been a more urgent time to be a landscape architect – the world needs our expertise! – and there are many paths they can take to pursue that career. It’s important to be aware of and stay open to the opportunities. You do that by reading widely, travelling, getting out into different landscapes, going to public events on campus and around the city, being engaged. University introduces you to the knowledge and skills needed to succeed in the field, but there are many other personal skills that university offers you and you need to take advantage of that.

I’ve really loved convening interdisciplinary electives that take Built Environment students into communities to work with residents. Another of my constant messages to students is: Design is a social act. So, developing a sense of social agency as future professionals is essential. Last year, we took a group of students to Manilla, NSW, a town which was about to run out of water. Seeing a regional town in drought was a real eye opener for most of the students and talking with people about how they deal with it. The students aren’t there to solve the problems of regenerating the life of a small town over a weekend, but it exposes them to other people’s reality.

We used to say “think globally, act locally”. And I think what may be happening now is there’s so much focus on global issues and emergencies, that it makes a lot of people feel a bit helpless. They don’t know how to act locally. When we address these issues in studio projects they can be brought home and personalized, helping students understand how they, as landscape architects, can have a positive impact on the local landscapes and systems we depend on.

Landscape architecture just such a rich and essential profession. It’s so expansive in terms of where and how you can work – anywhere along the continuum from the art and design end of things, to the science, ecology and technical end of things. At best, it’s a lifelong calling.