Landscapes of love

It might seem that Valentine’s Day is about chocolates, flowers and champagne. But if you want to escape yet another consumer trap, remember landscapes are free. Enjoy birds, bees and trees in public gardens or hold hands watching a breathtaking sunset.

One of the most enduring symbols of love is the garden. The walled garden or Hortus Conclusus is the garden of Paradise and symbol of chastity and the Virgin Mary. Within it, the Virgin subdues and coaxes the head of a unicorn into her lap while thorny roses bloom. This is not only a potent mix of sacred and profane, but a succinct biological metaphor.

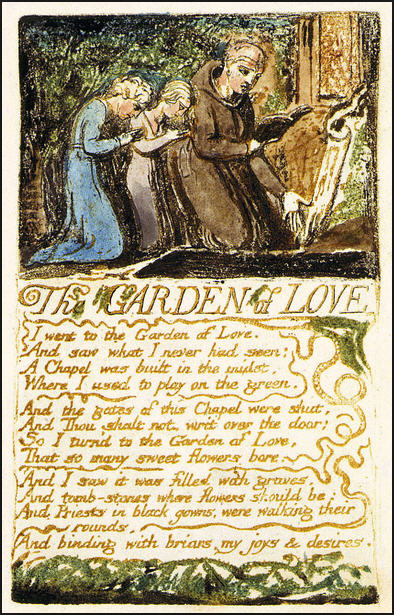

William Blake’s short poem ‘Garden of Love’ speaks plainly of liberty as the necessary precondition for love. Given the entwined messages of love and faith and freedom associated with Valentine’s Day, it is not surprising that some countries have banned its celebration or discourage public shows of affection. As a result, celebrating Valentine’s Day – synonymous with sentimentality and commercialism for many – becomes a form of rebellion and political activism in the streets of the city for others.

It was not until Geoffrey Chaucer wrote ‘The Parlement of Foules’ the in the 14th century, drawing on traditions of courtly love in the Age of Chivalry, that Valentine’s Day was popularised as a day for lovers. One of a few early saints named Valentinus – and one of several patron saints of lovers – Saint Valentine married soldiers who were forbidden to wed and generally ministered to loving Christians. Martyred by the Emperor Claudius, he wrote a final letter before his execution to the daughter of his judge, whose sight he had miraculously restored, signing it ‘Your Valentine’. On so slim an incentive, the tradition of writing love letters on Saint Valentine’s Day was based, and a mass greeting card industry was born.

Just as pagan celebrations such as the Saturnalia were integrated into Christmas, and life-affirming symbols filled Easter with rabbits and eggs, Valentine’s Day has blended symbols of love and lust. Blood-red hearts and flowers, arrows and naughty putti acknowledge those irresistible, universal rites of passage: the pursuit of desire, the anguish of uncertain affection, the joy of love won and pain of love lost.

Glitter contributes to ocean microplastic. Photo: Sharon McCutcheon

Lovers' locks are not longer permitted on city bridges for fear of their weight. Photo: Joakim Honkasalo

Helium foil balloons are a serious environmental polluter.

The simple kiss has seemingly infinite variety and complexity of meaning. Barbara Levine and Paige Ramey have documented kissing with Princeton Architectural Press, in a visual history both furtive and forthright that covers the “Victorian era through the Swinging Sixties smooch, canoodle, neck, and spoon. The collected photographs are sweet, sincere, and saucy, occasionally awkward, and always intriguing”. Kissing may be a sustainable expression of love, but what of the lead-up? We are encouraged to avoid the polluting, wild-life threatening, foil balloon hearts, glitter and resource-intensive hothouse flowers that flood cities on Valentine’s Day. Even the pastime of securing a lover’s lock to a public bridge is frowned on by cautious engineers. Luckily, the most consistently spruiked ingredient for a good time is a magical setting. And that can be found with a little, careful research.

The place for love

More powerful than poetry, prosecco, Peruvian single-origin chocolate or Pacific oysters, is the perfect place. It is no wonder that you pay a premium for your rooftop dinner view, riverside cocktails and rose-garden tea. An aphrodisiac heightening of emotion and sensitivity lies within the gift of location. If you are nervous about chatting, the full, wordless sensorium of landscape – the temperature, breeze, smells, sights and bodily immersion in a place – can do the talking for you.

There are many suggestions circulating to help realise a romantic Valentine’s day. Cities are busy promoting their top-things-to-do. But behind every listing of helpful recommendations for gorgeous private dining venues, dancing, intimate bars and glamorous hotel get-aways, film nights, theatre performances, poetry readings, chocolate hot spring dip, hiking, surfing or a date skate is a special landscape setting. And despite the emphasis on paid events and ticketed activities to excite and celebrate affection, the settings for love can be free.

San Fransisco is offering walking tours if you need guidance. Although we’ve just missed peak Melbhenge, the city itself still provides a spectacular frame and backdrop for sunsets at the moment. There are parks and gardens, birds and still some bees or butterflies, to be found in every city. Walk barefoot on some grass. Take time to admire a tree together. With the help of the City of Melbourne’s interactive tree database ‘Urban Forest Visual’ you can email a proxy Valentine to an understanding leafy listener in Melbourne, or now Vancouver too.

Top of any lovers’ list are high places with twinkling night-time views: the roof of buildings, multi-storey carparks, escarpments above neighbourhoods nestled glowing below in their plains and valleys. Perth has identified lookouts for intimate picnicking. The most romantic views in New York City for Valentine’s Day unfortunately only lists one free venue: the Empire State Building. Luckily, there are many more.

Most free spaces are associated with public buildings and facilities. Remember too that a peak-hour tram, train or bus ride is one way to get close to your beloved, while public transport can be worth the ride for the unique views too – and you can holds hands if you’re not driving. That said, one of the least strenuous and potentially most exciting ways to get to an elevated location is in a car.

Car cultures and canoodling

In Australia, as in America, the youthful enthusiasm for independence pursued by baby-boomers, simultaneously drove and was driven by the growth of car culture and love of the open road. It’s no coincidence that legal driving age corresponded with the urge to freely explore other things and gave rise to entertainments facilitated by cars. Cities bloomed with public carparks, roadside lay-bys, drive-in theatres, bridges and even some urban rooftops that served as settings for many a romantic movie moment as well as real-life tryst. Car freedom has continued to enable and expand the secret life of top beauty spots.

‘Lovers’ lanes’ are secluded areas where people kiss and make out. They are not just lanes however, but can include parking lots, tracks or other public ways. Although the phrase is recorded from 1853, the privacy and all-weather comfort of cars has linked lovers’ lanes to the youth of a modern automobile age. Vroom Girls, a website for women who love cars, provides a handy list of Californian lovers’ lanes in an empowered piece ‘Parking in Cars with Boys’. “Who needs to book a fancy restaurant this Valentine’s Day? We’ve got you covered with the perfect romantic setting — and you never need to leave your car.” There are more in Los Angeles with famous movie vistas around the bend of many a scenic drive. Melbourne has a few from watersides to the ranges above the city, described as ‘retro’ for a post-peak car era. But bad things can happen at lovely, lonely places, as the 1999 independent slasher film Lovers Lane makes clear. And it is a short step from lovers’ lanes to lovers’ leaps.

Australia is the home of the world’s oldest picture gardens still in operation. Sun Pictures opened on 9 December 1916, in Broome, with a full house. The first film to be played was a racing drama called Kissing Cup. Writing in 2009, Ian Willis considered the history of outdoor cinema and noted its resurgence. There are still many city venues for outdoor, rooftop and drive-in cinema. But “open air cinema really took off in Australia with the arrival of the drive-in movie theatre.” The drive-in story is full of nostalgia and romance for Australians today. “The ‘shaggon wagon’ that was a god-send for the drive-in” explains Willis. “The young stud would reverse into the spot, open the van doors and set up for a night of canoodling and occasional movie watching, all away from the prying eagle eyes of parents.” Willis also notes that the drive-in grew along with the suburbs and was “inclusive” and “democratic”, many also allowing ‘walk-ins’ without cars.

Not much is written of the architecture and site design of the drive-in. An early exception is the chapter ‘Of Motorcars and Movies: The Architecture of S. Charles Lee’ by Maggie Valentine in the 1990 Roadside America: The Automobile in Design and Culture. Then there’s the provocatively-titled 1994 ‘Forgotten Audiences in the Passion Pits: Drive-in Theatres and Changing Spectator Practices in Post-War America’ by Mary Morley Cohen in Film History. The landscape impact of outdoor cinemas can be seen in an early aerial of Hoyts’ Drive-in Theatre, Boronia Road, Wantirna in Greater Melbourne. Designed by Peter Muller and now abandoned, it was one of the last drive-ins to open in Melbourne in 1968, expanding with a second screen in 1983. Only last year Coburg’s popular drive-in was offered for sale, although leased to run for another 10 years. It is one of just three left in the Melbourne area – the first city in Australia to open a drive-in in Burwood 1954 – alongside the Lunar Drive-in at Dandenong and the Dromana Drive-in on the Mornington Peninsula.

William Blake’s Garden of Love was published in 1794 as part of his collection, Songs of Experience.

Portable digital technology is making it easy to have impromptu outdoor cinema during good weather. “In the US” says Willis “a new drive-in cult has emerged, the guerrilla drive-in. Young folk congregate in an industrial area and project a movie on the blank wall of as warehouse.” In the same way and with creativity enabled by new location and communication technologies, keen couples can find any number of places to entertain each other on Valentine’s Day.

The wonderful landscapes of our cities spoil us for choice, reminding us that it is more important to be in the multi-sensory moment with our significant other, than in the frame of an Instagramable selfie.