Jane of Arc

A new documentary ‘Citizen Jane: Battle for the City’ illustrates the social and political climate of the famed New York urban activist Jane Jacobs. Yet its simple tale of ‘David and Goliath’ does not tell the whole story.

It’s hard not to compare the recent documentary on writer and urban activist Jane Jacobs, with the biography of her nemesis, The Power Broker: Robert Moses and the fall of New York, which was written almost half a century before it. Citizen Jane: Battle for the City is ostensibly a portrait of Jacobs, whose book The Death and Life of American Cities helped mobilise a profound and global shift in how we understand the way that cities work and the role of the citizen within them. The documentary however is less interested in unpacking the person behind this seminal book, than in prosecuting an ideological critique of modern planning, exemplified by the polarising figure of Moses.

For sure this era of planning by brute government force is crying out for a robust critique, but there is a price to pay in this documentary. In substantially reducing Jacobs the writer to Jacobs the activist figurehead holding back the dozers, with the televisual drama of public skirmishes and the menacing spectre of the developers wrecking ball, Citizen Jane leaves you hungry to know more about Jacobs the person. How is it that the girl who grew up in a quiet protestant home, whose father was a doctor, mother a teacher and brother who grew up to be a judge, arrived in New York and immediately fell in love with the epicenter of bohemian, gender diverse and creative New York: Greenwich Village? There is not enough of the self-trained and determined female author in a world full of men, the deep thinker and shrewd communicator, the writer of six other major books on urbanism and society that followed Death and Life, and of course, (as with all heroes) the flaws. These will have to wait for another documentary.

Meanwhile Robert Caro’s Pulitzer prize-winning and spectacular portrait of Robert Moses, arguably America’s most powerful city builder, takes you on an expansive, yet nuanced journey, through the buccaneering exploits of New York’s (almost) indomitable urban czar. As comprehensively detailed and researched as the book is of the social and political fabric within which Moses wove his powerful plans, it is also much more than a history of people, places and events. It takes the reader through a meticulous portrait of a deeply conflicted person, driven by both a commitment to public service and private ambition, a person capable of acting in the spirit of both lifelong loyalty and vindictive revenge, and yes, a person who would ride roughshod over neighbourhoods and communities, while also being responsible for the building of hundreds of new city parks, playgrounds, swimming pools, and other recreational facilities.

To some extent this is an unfair comparison. One is a book over a thousand pages long, while the other is a 92-minute documentary. Documentaries require complex stories to be distilled into consumable chunks. You can’t say everything, so, to borrow a phrase from the analogue era, much is left on the editing floor. Didacticism is rewarded while uncertainty is discouraged, even when a subject is deeply infused with wicked complexity. And American cities were nothing if not a complex urban experiment during the massive and rapid economic expansion of the post war years (which bears more than a passing resemblance to the urbanisation of China since the ’90s).

Washington Square Park pictured in the mid-20th century. Image courtesy of the New York Public Library.

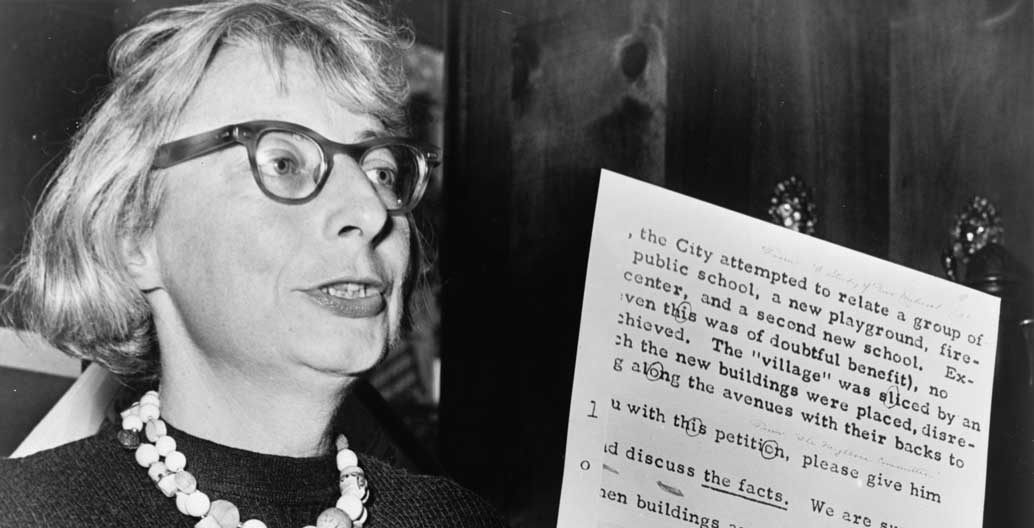

Jane Jacobs, pictured as chair of the Committee to Save the West Village (1961).

Citizen Jane does however paint an evocative picture of street life in New York at this time. It pops and sizzles with archive footage from the 50’s and 60’s; street vendors and kids playing catch, hobos and party frocks, and lots and lots of people on the streets. These scenes are set against another side of what was happening in American cities at that time; exploding with infrastructure projects, large-scale ‘urban renewal’ of older districts, on-going rural migration to the city and consequent housing stress, along with the historic social challenges of entrenched racial inequality.

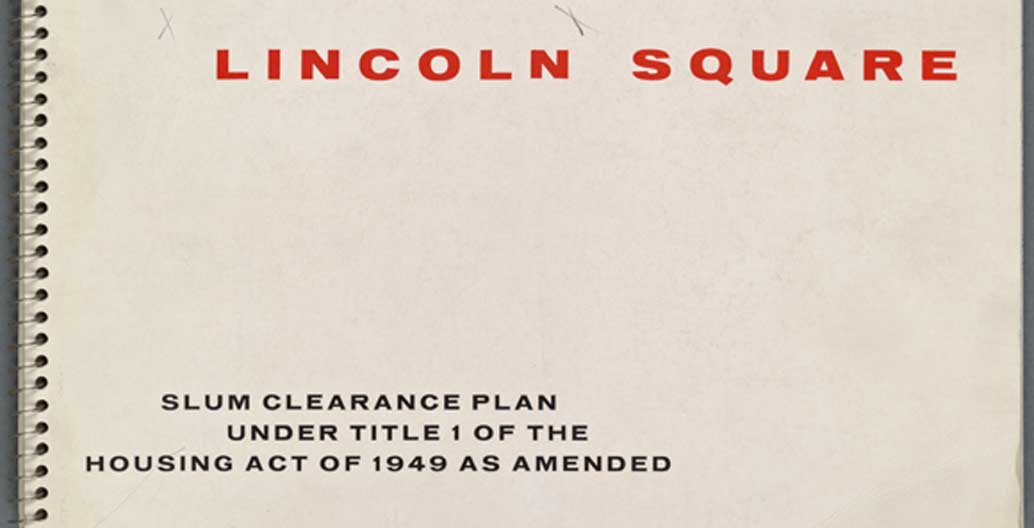

Jacobs was an observer of all this. She was a committed citizen of Greenwich Village, where she lived for most of her time in New York. For a time she built a solid career writing about architecture for newspapers and magazines, becoming an associate editor of Architectural Forum in 1952. The documentary reveals how, having initially written a positive report on plans for an urban renewal project in Philadelphia, she had a revelation on a return tour of the completed project, that would change her writing forever. She found empty streets, desolate playgrounds and a community traumatised by the upheaval. Meanwhile those neighbourhoods that were still to be ‘renewed’ were teaming with life and social cohesion. Interviewing the renowned urban planner Edmund Bacon, who was the development’s architect, Bacon dismissed the failure of the new public domain as the fault of the residents. They weren’t using it ‘as they were supposed to’.

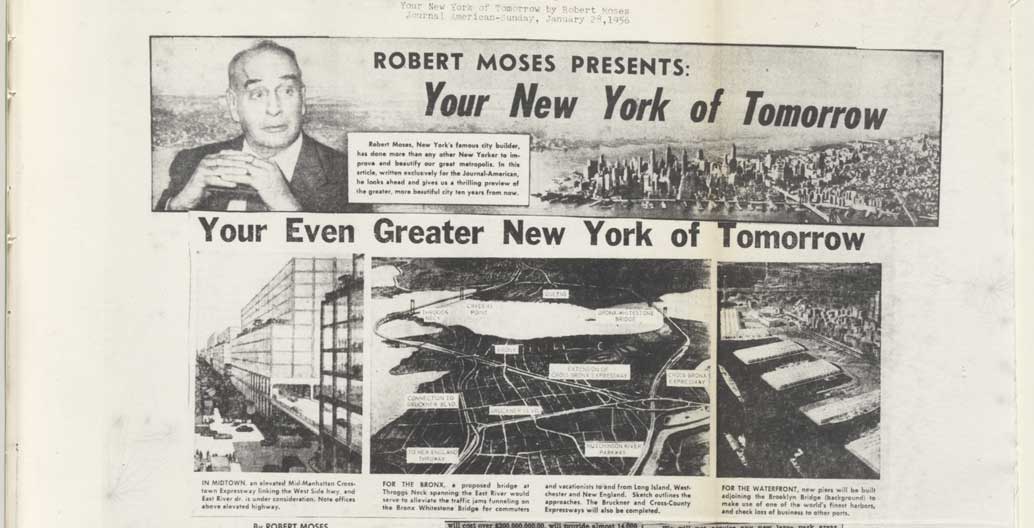

While Bacon’s hopelessly top-down approach has its roots in a number of different factors, the documentary throws emphasis on one: the Swiss architect and urban designer Le Courbusier, who promulgated his vision for la Ville Radieuse (The Radiant City) while visiting America. His was a vision that separated the city into zones of work, rest and play, while concentrating buildings into dense clusters, surrounded by a utopian vision of green parks, fresh air and sunlight. These distinct zones were stitched together with great swathes of multi-lane high-speed highways.

As Jacobs scrutinised the early results of this new ‘sanitised’ approach to separating a city’s functions, she realised that the entire ethos underwriting America’s urban transformation was wrong. In particular, Jacobs locked horns with the prevailing planning norm that prioritised cars and the roll out of blacktop, over much of the city she loved. A second key moment in Jacobs’ life relates to a proposed highway through the heart of Washington Square Park and Lower Manhattan. It would have split the park into two halves, connected only by an elevated pedestrian walkway. It immediately fomented public protest, with Jacobs at the heart of those protests. She mobilised a public army (in particular young mothers), that was so effective, the Mayor eventually ran scared of the press attention and canned the highway in a single memo. It was the first major defeat for the powerful Robert Moses.

If the documentary is limited in the detail with which it draws a human portrait of Jacobs, it portrays Moses as little more than a villainous stick figure. Yes, no doubt his opinions on slum clearances as a means to ‘cut out the cancer’ of miscreant behaviour, profoundly misunderstood the delicate social networks that made poor neighbours surprisingly resilient and dynamic environments. Yes, his privileging of cars above all else failed to understand the vital importance of pedestrian occupation of the city. But as Caro’s biography makes clear, Moses was far from a two dimensional baddy.

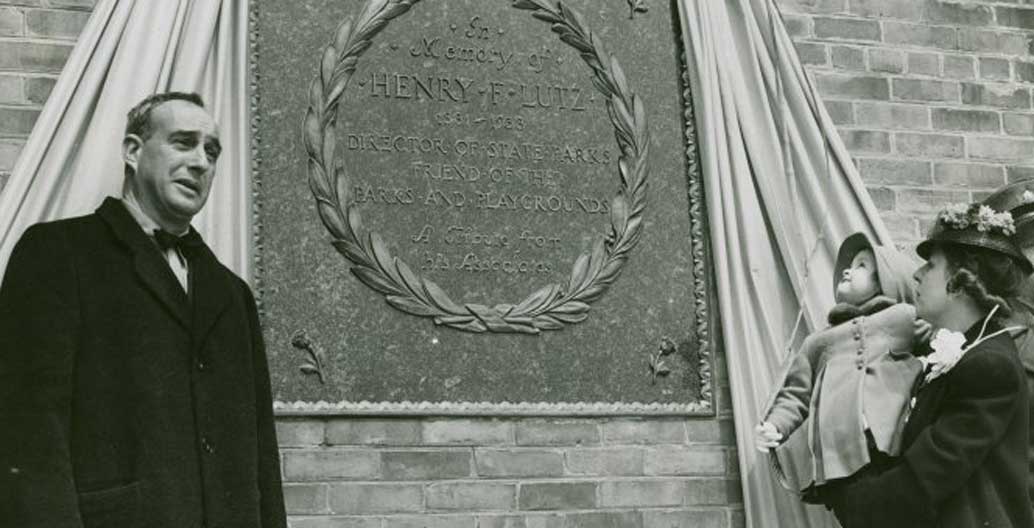

Moses’ early life was spent reforming the rampant corruption of public life. Given his later immense power, it is ironic that his early life repeatedly confronted intergenerational and sectional cronyism. While he benefited from his connections with the ‘Tammany Hall’ community, his early political career was one of fighting corruption and risking more than his career, in cleaning up public spending on the city.

The highways he so loved were not just for commuter convenience, or the benefit of General Motors. Moses had a vision that ordinary working class families could get in their car in the stifling summer months, head to Long Island, and swim. As a passionate swimmer who wanted ordinary people to have access to nature, as respite from the city.

With his ambitious plans to build bridges and roads to open up access to Long Island, he didn’t just meet resistance from the average citizen. He also came into direct conflict with some of the richest and most powerful families in America, who had bought up and effectively locked up, most of the island. The Vanderbilts, the Pratts, the Morgans, all fought tooth and nail to retain their beach fiefdoms, and Moses had to use his full executive authority to outsmart and outmanoeuvre them.

If Moses could have learned a lot from Jacob about the fine grain social ecology of the street, she could have learned a lot from Moses about the nexus of money, politics and state power that underwrites so much of how a city functions, then and now. And while no less than three of Jacobs other books are focussed on the economics of the city, the lasting legacy of Jacobs’ life and work, as evidenced in this documentary, is one that almost entirely blames the planners for a city’s failings, not the structural political and economic drivers that typically sit behind poor planning decisions.

Robert Moses in front of plaque dedicated to Henry Lutz (1945). Image courtesy of the New York Public Library.

'Your New York of Tomorrow', (1956). Image courtesy of the New York Public Library.

Slum clearance report from the New York City Housing Authority (1949). Image courtesy of the New York Public Library.

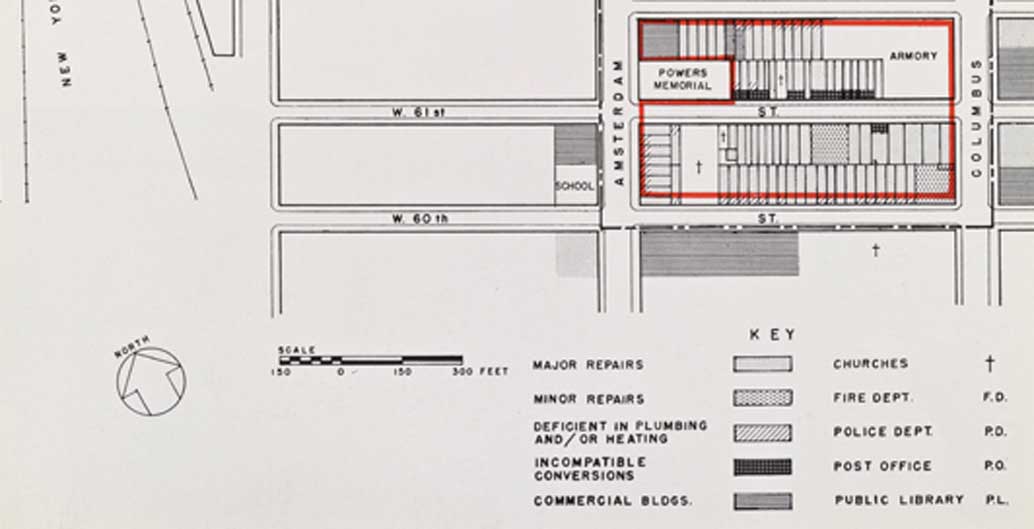

Committee on Slum Clearance, report on Lincoln Square (1949). Image courtesy of the New York Public Library.

(Detail): Committee on Slum Clearance, report on Lincoln Square (1949). Image courtesy of the New York Public Library.

Robert Moses causeway bridge, New York.

This may explain why the most effective examples of Jacobs’ community action were all individual acts of resistance. She did not, for instance, campaign for more systematic reform of regulation and zoning laws, to enshrine diversity within planning codes. She did not campaign for rent controls or against systemic racial bias in housing programs, nor did her writing sufficiently address the macro-economics that promoted ‘white-flight’ from the cities to the suburbs. She aimed her condemnation squarely at modern planning, with such quotes as, “There is no logic that can be superimposed on the city; people make it, and it is to them, not buildings, that we must fit our plans.” However, if we define ‘people’ as a local community that assumes the right to determine local planning decisions, we see the limits of such ‘direct democracy’ in the many planning decisions that routinely frustrate citywide and regional growth plans, otherwise known as NIMBYism.

Citizen Jane narrates one side of the story of New York’s postwar growing pains, very well, reminding us of what collective bottom-up activism can achieve. TIME once described her as “the blunt poet laureate of the way modern cities really work”, and while this is true of her observations of how the modern city street works and the behaviour of the streets users and inhabitants, it is less true of her understanding of the political and economic machinery of the modern city.

As a model for strategic urban planning and development, Jacob’s work remains problematic when scaled up beyond the local, particularly when social and spatial forces meet head-on with the forces of money and power. As we know in politics, being an effective opposition party is one thing, but what do you do when you get into power? As poignantly stated by the writer, architect and urban advocate Michael Sorkin, towards the end of the documentary: “The problem for people who are designing and thinking about this new urban tissue that’s being created, is how to take some of these incredibly valuable lessons that Jane Jacobs teaches and then apply them to the project of creating the places where all these billions of people are going to live.”

There are many reasons to be inspired by this film and to celebrate the work of this remarkable campaigner for the rights of citizens, however Sorken’s question remains unanswered. It is perhaps salient to note that as many cities face housing affordability challenges, Jacobs’ charming West Village two bedroom home, which her campaigns helped protect, is now valued at over $4m. Whether Jacobs likes it or not, the life of the city and its urban fabric is indeed subject to many forces and factors that are superimposed upon it.