Greener places, better lives, deeper pockets

New South Wales’ ‘Greener Places’ draft policy marks an important step in the design and delivery of green infrastructure. It aims to place trees and parks on a par with roads and energy. But without proper funding it may struggle to leave an integrated ‘legacy of great spaces and greener places’.

The value of green infrastructure is at the core of the recently released Greener Places draft policy document, courtesy of the New South Wales state government. And the state does value our natural environment, doesn’t it? The pleasant park nearby, the old tree that holds memories of over 100 years, the lovely creek where platypus used to swim and fish could be caught. Most people are very aware of the role the natural environment plays in their quality of life.

Despite this, nature is routinely overwhelmed by investments in roads, rail and other concrete artifacts. Have you ever seen an announcement for A$3 billion in green infrastructure? Probably not. Yet this is routine when it comes to allocating budgets for transport, sports stadia and sewage infrastructure.

So the question is: Do state governments really value their natural environments? Looking at our public investments, it doesn’t seem like it. This new policy is, therefore, of enormous importance. It not only claims that green infrastructure has an equal position to other infrastructures, it makes it clear that greening the city can have huge benefits for our health and for our environment, bringing a return on investment that a road never could.

For the first time in NSW’s history, a comprehensive design-led policy for green infrastructure has been developed, aiming to set green spaces on the policy map, equal to road, sewage, or housing infrastructure. This implies a huge step forward in the way green infrastructure is treated and looked at. Instead of being of lesser importance, and hence losing out in the face of economic development, this document aims to put our green resources at least on the same level. This is commendable.

In his foreword to the policy, the Minister for Planning Anthony Roberts states, “By prioritising green infrastructure now, we will leave a legacy we can be proud of. A legacy of great spaces and greener places”. Following up these comments, the NSW Government Architect acknowledges, “Green Infrastructure needs to have a more influential role in the planning of cities and urban environments. It needs to be considered as essential infrastructure at the outset of the design process, from strategy through to concept design, construction and maintenance”. These statements sound firm and make you want to read more.

In Sydney's west, greening is an urgent necessity, to combat the area's heightened urban heat island effects. Image: Maksym Kozlenko

Sydney's Homebush Bay has witnessed novel green developments, such as this unplanned shipwreck garden. Image: Jason Baker

'Greener Spaces' places an emphasis on breaking down the siloes between Sydney's green lungs. Image: Jorge Láscar

Other parts of NSW stand to benefit from the policy, including cities like Newcastle. Image: Daniel Silk

Green First!

And what a good policy it is. In a clear comprehensible way it establishes the importance of a connected green system, delivering all sorts of functions, from health benefits to environmental benefits, topped off with climate change adaptation, predicted to deliver huge economic windfalls.

Greener Places also establishes a policy position that is systemic. The system of waterways and desired ecological connections determine the connectivity that enhances the lives of people living in every part of NSW. Without connecting the different parts of these systems there is no whole. Our natural environment is reduced to individual bits and pieces, without coherence and each lacking quality. Rather, the policy argues that Hyde Park is connected to the Royal Botanic Gardens, which is connected to the waterfront, as a continuous system for moving and sustaining people, animals and ecologies.

The policy states that every person in the state is entitled to have easy access to green space, and for good reason. Evidence suggests that even looking at green space behind a glass window increases people’s health. Being able to spend time in a green environment may also decrease domestic violence, improve mental health, and heart and lung functions, thereby improving overall wellbeing. This means green infrastructure has an enormous potential impact on healthcare costs.

Included in the policy is a scheme to support homebuyers to plant a tree, resulting in an ambition to plant hundreds of thousands of trees in the coming decades. There are good reasons to do this. It raises awareness that trees give shade, bring nature close by and they look great, especially when they have grown to reasonable sizes. Every tree that survives will be an extra piece of nature in the city.

“Every tree that survives will be an extra piece of nature in the city” – @UTSresearch’s Rob Roggema

The risk however, is that after the first plantations, especially if the trees are no more than tendrils, the ‘trees-as-presents’ will be neglected or simply removed by the adopting parents. Then the scheme might be counterproductive and a loss of invested money. To give everyone a tree does not bring structural investment to green infrastructure, as Greener Places intends. In this sense it would be a collateral benefit if these trees created the green infrastructure the policy intends to facilitate.

Without structure and connection, such as the creation of green laneways or boulevards, the trees will be randomly divided over the state, and be reduced to bits and pieces. When trees are seen as individual elements in the city, they are not part of a broader embedded system, and have limited health benefits, as described before. The policy makes a strong case for the importance of connectivity: of connected laneways, green boulevards, parkways, parks, and waterways. However, the question is, if the ‘free tree’ will be planted, and if it survives, is it contributing to the bigger system?

Newcastle Wetlands. Image: Doug Beckers

Planter boxes, like this one in Erskineville, stimulate an area's social connectivity.

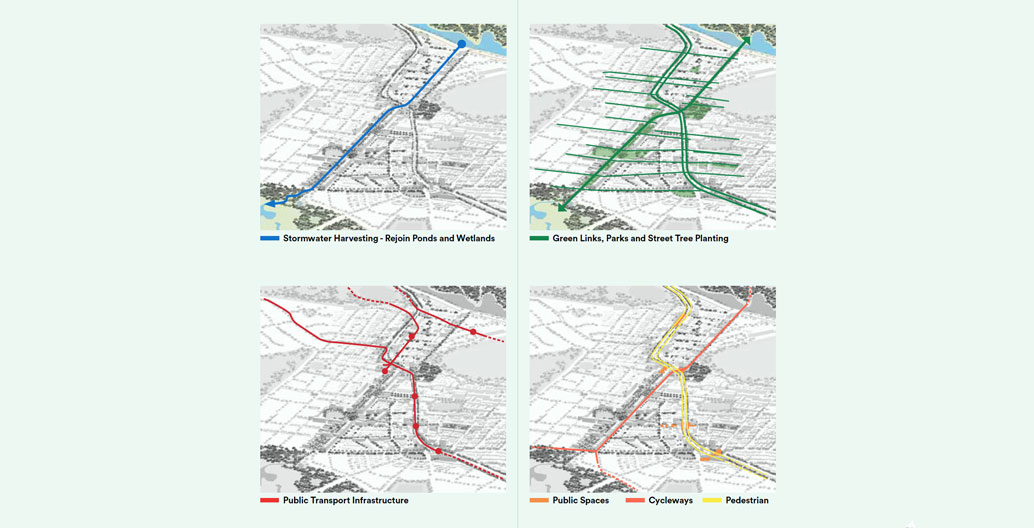

The document's analysis of a street's different overlays – this time including green links.

Can Sydney's historical verdant wealth be spread more equally through the city? Image: Sardaka

Creating structural change

If potentially billions of dollars are to be spent on green infrastructure, this needs to be a structural approach, with a vision on how to create the lanes and boulevards as part of a bigger green system. This green infrastructure should always be based on the water and ecological systems forming the landscape, and should be extended to where it often does not currently reach, deep into the concrete jungle we call neighbourhood.

The government should be willing to own these green spaces, especially the principal green structure that forms the backbone of Sydney’s metropolitan area. This means investing in green spaces that are developed now as beautiful spaces, but later grow in invaluable and beautiful places that people remember as the backdrop to important happenings.

How can we create a budget that on the one hand provides the capital investment to deliver these spaces, as well as the yearly operational investment to maintain these places for longevity? Currently budgets are too low to effectively create green infrastructure that is as valuable as other forms of infrastructure. Green and blue (water) infrastructure should be an integral part of every development, with budgets allocated to invest in it.

As the policy rightly points out green and blue infrastructure deserves a more dominant role in the establishment of new developments, and revitalising existing urban areas. But it also requires investment to preserve and acquire landscape, which then functions as the basis for life in urban precincts. As a general rule, at least ten percent of our urban areas should be devoted to green-blue spaces. Often current budgets are inadequate to make this possible. Beyond the square metres, more is required to make and keep a high level of green spaces. It is a matter of both quantity and quality.

For instance, what if NSW creates a fund for green spaces, where property developers donate a percentage of the overall development value (say one percent) towards the fund? This would soon be filled with the needed budget for maintenance. State government could also ask residents to donate, say a fraction of the value of their house, on a yearly basis to the green fund. This should be understood not as an extra cost, but an investment, recognising that residents will be healthier and will live longer lives, as a result of their proximity to high quality green spaces. Health insurance companies could donate a percentage of their premiums to the fund, as they benefit from healthier customers who have reduced illness and less expensive surgery bills.

Getting green on-side

Alongside such budgetary considerations, public consciousness regarding the quality of green spaces should also be enhanced. Despite the many excellent examples of great parks and green environments in Sydney, there are also many areas that are not designed with much love. Look at the endless streets lined with car dealerships, Bunnings, Officeworks and other ‘big box’ retail. Or consider WestConnex, where an abundance of trees could have created a green parkway, instead of a scar in the urban landscape.

Of course such spaces would have limited budget and space for green investment, but the creativity starts when the going gets tough. Impossible design problems are the best to tackle. If we could turn road infrastructure or retail strips into real green infrastructure, where people like to come, then this would bring both positive environmental and commercial outcomes. Genuine attention to the design of these spaces, which are currently so neglected, bringing together experienced designers and local council teams, could co-create a green Walhalla. Design excellence could then extend beyond high profile central sites, with a process of continuous debate about the spatial quality desired and proposed.

Green Places deserves to be taken seriously. Very seriously. Green infrastructure should indeed be valued in the same way as roads and sewage. However, without funding mechanisms, such as briefly proposed here, the policy remains a policy. Nice to have!

But if NSW had a functioning green fund, with green principles rolled out as a part of every development, connected and integrated in urban fabric, opening the opportunity to turn the ugliest streets into green beauties and buildings into edible constructs, the policy could become a must have.

Then every space can be designed with care, with attention to the natural environment bringing a better life for everyone. Name me one politician that doesn’t want to have that on their CV? Praise be the commissioner that generates a green fund that makes this possible.

––

Greener Places is a draft policy document. It aims to promote discussion about what the final policy should address. All feedback on this policy will be considered and a final version will be developed in early 2018. Submissions are welcome.

Prof Dr Ir Rob Roggema is Professor of Sustainable Urban Environments at the Faculty of Design Architecture and Building, University of Technology Sydney.